Iran’s nuclear program remains a top focus for inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency, particularly as any possible deal between Tehran and the United States over the program would likely rely on the agency, long known as the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog.

This week, Western nations will push for a measure at the IAEA’s Board of Governors censuring Iran over its noncompliance with inspectors, pushing the matter before the UN Security Council. Barring any deal with Washington, Iran then could face what’s known as “snapback” — the reimposition of all UN sanctions on it originally lifted by Tehran’s 2015 nuclear deal with world powers, if one of its Western parties declares the Islamic Republic is out of compliance with it.

All this sets the stage for a renewed confrontation with Iran as the Mideast remains inflamed by Israel’s war on Hamas in the Gaza Strip. And the IAEA’s work in any case will make the Vienna-based agency a key player.

Here’s more to know about the IAEA, its inspections of Iran, and the deals — and dangers — at play.

The IAEA was created in 1957. The idea for it grew out of a 1953 speech given by US President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the UN, in which he urged the creation of an agency to monitor the world’s nuclear stockpiles to ensure that “the miraculous inventiveness of man shall not be dedicated to his death, but consecrated to his life.”

Broadly speaking, the agency verifies the reported stockpiles of member nations. Those nations are divided into three categories.

The vast majority are nations with so-called “comprehensive safeguards agreements” with the IAEA, states without nuclear weapons that allow IAEA monitoring over all nuclear material and activities. Then there’s the “voluntary offer agreements” with the world’s original nuclear weapons states — China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the US — typically for civilian sites.

Finally, the IAEA has “item-specific agreements” with India, Israel, and Pakistan — nuclear-armed countries that haven’t signed the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty. That treaty has countries agree not to build or obtain nuclear weapons. North Korea, which is also nuclear armed, said it has withdrawn from the treaty, though that’s disputed by some experts.

Iran’s 2015 nuclear deal with world powers, negotiated under then-US president Barack Obama, allowed Iran to enrich uranium to 3.67 percent — enough to fuel a nuclear power plant but far below the threshold of 90% needed for weapons-grade uranium. It also drastically reduced Iran’s stockpile of uranium, limited its use of centrifuges, and relied on the IAEA to oversee Tehran’s compliance through additional oversight.

But US President Donald Trump, in his first term in 2018, unilaterally withdrew America from the accord, insisting it wasn’t tough enough and didn’t address Iran’s missile program or its support for terror groups in the wider Middle East. That set in motion years of tensions, including attacks at sea and on land.

Iran now enriches up to 60%, a short, technical step away from weapons-grade levels. It also has enough of a stockpile to build multiple nuclear bombs, should it choose to do so. Iran, which is sworn to he destruction of Israel, has long insisted its nuclear program is for peaceful purposes, but the IAEA, Western intelligence agencies, and others say Tehran had an organized weapons program up until 2003. Uranium enriched to 60% has no known civilian use.

Under the 2015 deal, Iran agreed to allow the IAEA even greater access to its nuclear program. That included permanently installing cameras and sensors at nuclear sites. Those cameras, inside metal housings sprayed with a special blue paint that shows any attempt to tamper with them, took still images of sensitive sites. Other devices, known as online enrichment monitors, measured the uranium enrichment level at Iran’s Natanz nuclear facility.

The IAEA also regularly sent inspectors into Iranian sites to conduct surveys, sometimes collecting environmental samples with cotton clothes and swabs that would be tested at IAEA labs back in Austria. Others monitor Iranian sites via satellite images.

In the years since Trump’s 2018 decision, Iran has limited IAEA inspections and stopped the agency from accessing camera footage. It’s also removed cameras. At one point, Iran accused an IAEA inspector of testing positive for explosive nitrates, something the agency disputed.

The IAEA has engaged in years of negotiations with Iran to restore full access for its inspectors. While Tehran hasn’t granted that, it also hasn’t entirely thrown inspectors out. Analysts view this as part of Iran’s wider strategy to use its nuclear program as a bargaining chip with the West.

Iran and the US have gone through five rounds of negotiations over a possible deal, with talks mediated by the Sultanate of Oman. Iran appears poised to reject an American proposal over a deal this week.

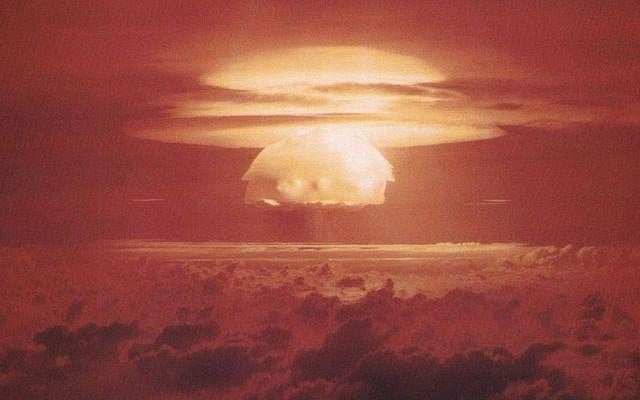

Without a deal with the US, Iran’s long-ailing economy could enter a freefall that could worsen the simmering unrest at home. Israel or the US might carry out long-threatened airstrikes targeting Iranian nuclear facilities. Experts fear that Tehran, in response, could decide to fully end its cooperation with the IAEA, abandon the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, and rush toward a bomb.

If a deal is reached — or at least a tentative understanding between the two sides — that likely will take the pressure off for an immediate military strike by the US. Gulf Arab states, which opposed Obama’s negotiations with Iran in 2015, now welcome the talks under Trump. Any agreement would require the IAEA’s inspectors to verify Iran’s compliance.

But Israel, which has responded to Iranian-backed terror groups across the region following their attacks, remains a wildcard on what it could do.

These clashes came after the Hamas-led onslaught on southern Israel on October 7, 2023 — when terrorists from Gaza killed 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and took 251 hostages to Gaza, sparking the ongoing war in Gaza.

Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, and other Iranian proxies across the Middle East launched attacks on Israel in support of Hamas.

Last year, Israel carried out its first military airstrikes on Iran in response to the Islamic Republic’s first direct missile attacks on the Jewish state in April and October — and has warned it is willing to take action alone to target Tehran’s program, like it has in the past in Iraq in 1981 and Syria in 2007.