In most Jewish circles, it is well known that Tisha B’Av, the ninth day of the Hebrew month of Av, marks the destruction of both Jewish Temples in Jerusalem in ancient times. Widely unknown is the fact that 96 years ago, Tisha B’Av in Jerusalem marked ground zero of the Arab-Israeli conflict, when deadly riots in British Mandate Palestine were ignited, culminating in one of the worst pogroms ever perpetrated outside of Europe. The 1929 massacre in Hebron set in motion the forces that continue to fuel this conflict today.

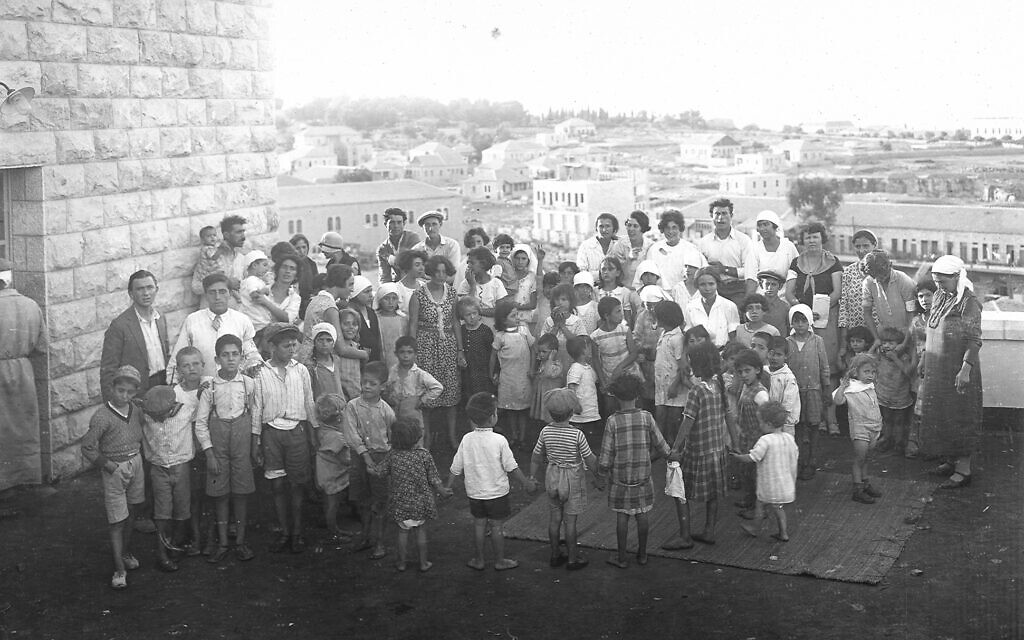

On Tisha B’Av of 1929, a Jewish demonstration at the Western Wall was met with a cascade of violence that reached its peak on August 24, 1929, in Hebron, when 67 unarmed Jewish men, women and children were slaughtered by their Muslim neighbors, and dozens more wounded. Many of the victims knew their assailants by name. For centuries, Muslims and Jews had lived harmoniously in Hebron, the burial place of Abraham. This was when the holy city went from being a symbol of coexistence to the antithesis of it.

In the days after the massacre, the British High Commissioner of Mandatory Palestine, Sir John Chancellor, wrote in his diary of what he witnessed in Hebron, “I do not think history records many worse horrors in the last few hundred years.” The hundreds of Jews who survived were evacuated by the British and forced to leave Hebron, exiling one of the world’s most ancient Jewish communities.

This dramatic turning point not only transformed Hebron, but the conflict itself, strengthening the Zionist movement, the Haganah, and later inspiring the settlement movement to revive Hebron’s ancient Jewish quarter. It also marked the birth of the central forces that drive this conflict today, most importantly the weaponization of the Al-Aqsa Mosque and disinformation surrounding a Jewish plot to destroy it. This supposed plot motivated the riots of 1929 and the Hamas-led onslaught on southern Israel on October 7, 2023, which the terror group had dubbed the Al-Aqsa Flood. The century-old Hebron massacre is also one of the first examples of Western appeasement of terror. The British went on to blame the Arab riots on the peaceful Jewish demonstration on Tisha B’Av.

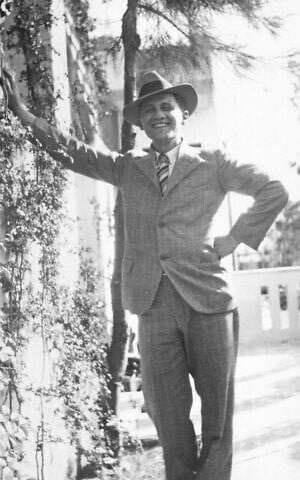

Below is an excerpt from the first half of “Ghosts of a Holy War,” a new book detailing that pivotal moment in Israel’s pre-state history and its haunting reverberations today. Drawing a direct line between August 1929 and the October 7 atrocities, the first part of the book is told through the letters of David Shainberg, a 22-year-old American from Memphis, Tennessee, who was studying in Hebron during this tumultuous time. The second section details the lasting impact of the Hebron massacre, painting a vivid portrait of its aftershocks throughout the decades, including on October 7 and beyond.

On August 14, 1929, David and a few of his friends walked to the dirt road leading to Jerusalem and took a taxi bound for the Wailing Wall. It was the afternoon before Tisha B’Av, the Ninth of Av, the most mournful day on the Hebrew calendar, the date that earned the Wailing Wall its name. It was on this day that both the First and Second Temples were destroyed, first by the Babylonians in 586 BCE, then by the Romans in 70 CE, sending the Jews of ancient Israel into their 2,000-year exile. On the Ninth of Av in the year 135 CE, the Roman Empire crushed the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

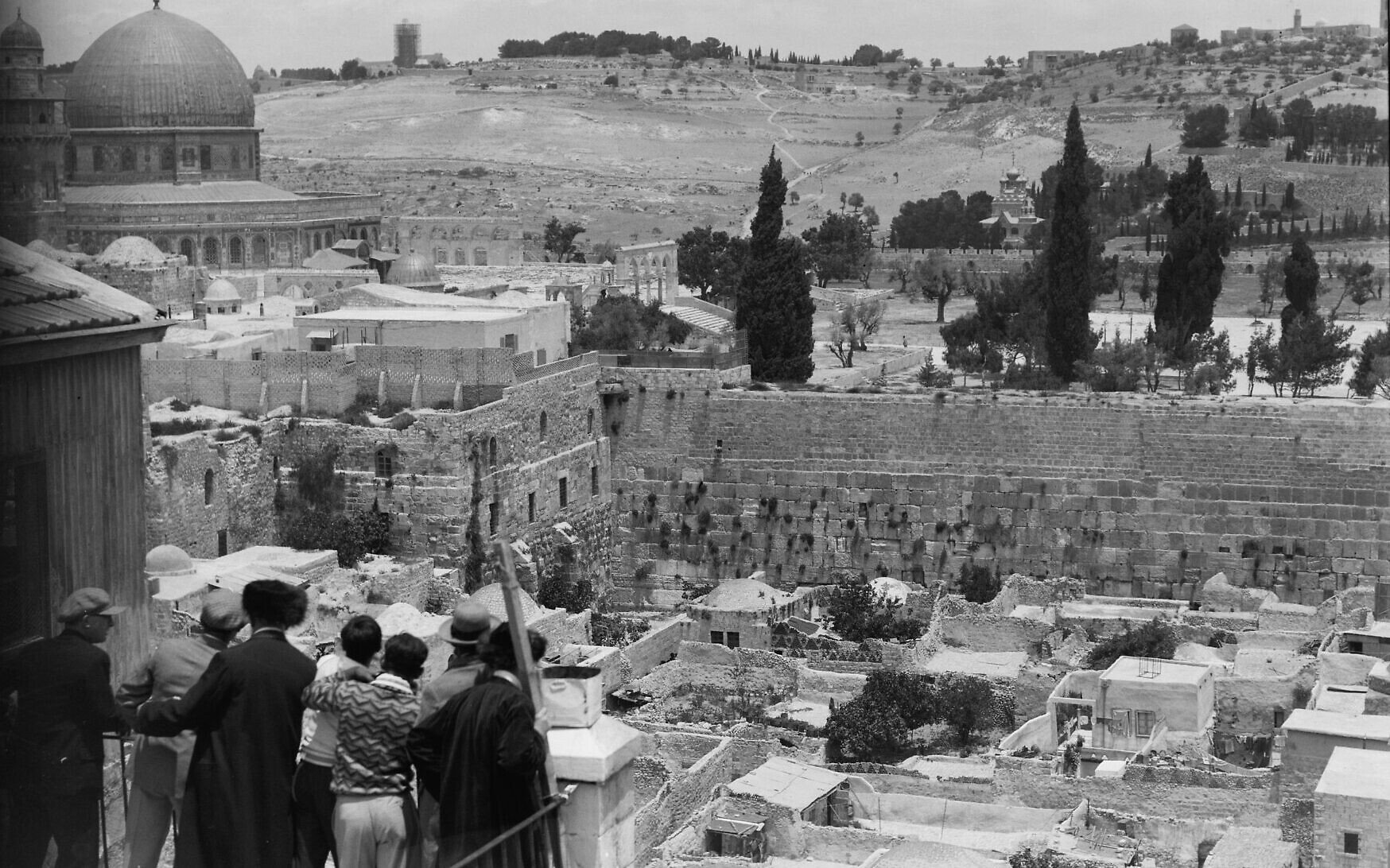

As the last remnant of the Temple Mount, the Western Wall is the centerpiece of Jewish grieving on the Ninth of Av, a day of mourning and fasting. Shortly after the sun set over Jerusalem that evening, David joined 10,000 Jewish worshippers in the annual pilgrimage to the wall. The few who were lucky to get close enough pressed their hands and faces into the ancient stones.

David and the throngs of men and women around him swayed as if in a trance, chanting from the Book of Lamentations. As their ancestors had done for centuries, they wept over the fall of Jerusalem, and cried out for the redemption of the children of Israel. This year, their grief carried a new layer of pain.

“Jerusalem has been in a state of constant excitement and tension for ten months now, and on Tisha B’Av this tension reached almost the breaking point,” David wrote to his father. “A visit to the Wailing Wall brought our national tragedy home to us in the strongest sense.”

The tensions between the city’s Jews and Muslims over Jewish rights at the Wailing Wall had increased since the incident on Yom Kippur. The Grand Mufti had since initiated various new building projects in the already cramped space, leading Jews to complain that it was the Muslims, not the Jews, who were violating the site’s fragile status quo. The British hoped to prevent any clashes, as Jewish mourners would pray at the wall throughout the night and into the next evening. Opposite the masses at the wall stood rows of British police, on foot and horseback, guarding the worshippers.

A week earlier, a Muslim man smoking a cigarette attempted to pass through a group of worshippers at the wall. When one of the men asked him to wait until they had finished their prayers, the smoking man hurled a stone at him. The week before that, two Jewish worshippers were assaulted by Arabs. The narrow corridor at the wall where Jews prayed had almost never been visited by Muslims until that incident on Yom Kippur in 1928. Sheikh Hasan Abu Sa’ud, a prominent Jerusalem preacher and associate of the Grand Mufti, had since used his sermons to encourage Muslims to visit the wall. Now it was a popular destination for anyone looking to harass Jews.

What most infuriated the Jewish community was the British approval in late July 1929 of the Grand Mufti’s construction of a new doorway at the Western Wall, leading directly to the Temple Mount, which was off limits to Jews. The cramped alleyway where Jews were permitted to pray at the Western Wall had since become a busy passageway for Muslims walking to and from Al-Aqsa through the Jewish prayer space. Arab attacks on Jewish worshippers at the wall became ever more frequent.

Soon after construction of the doorway commenced, Joseph Klausner, a distinguished historian and professor of Hebrew literature at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, established the Pro–Wailing Wall Committee to resolve the growing crisis at the world’s holiest site for Jewish prayer. Klausner was frustrated by the failure of the Zionist leadership to protect Jewish worship at the wall. Mainstream Jewish leaders tried to quell the influence of Klausner’s group. They didn’t want to anger the British, whose support they were existentially dependent upon.

Hearing of a planned demonstration against the British at the Western Wall, the Zionist Executive tried to have it canceled. Failing to dissuade organizers, the executive published statements in various newspapers, urging calm while they tried to negotiate the issue with British authorities.

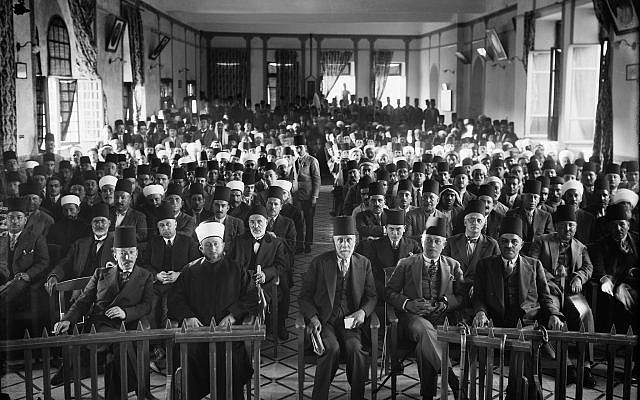

Muslim leaders, and Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini in particular, made no such effort. On Friday, August 2, the mufti’s Society for the Defense of Al-Aqsa Mosque held a meeting at Al-Aqsa attended by thousands of Muslims. They made an oath “to defend The Holy Buraq and the Mosque of Aqsa at any moment and with the whole of their might.”

In the leadup to the Ninth of Av, Klausner’s Pro–Wailing Wall Committee used the pages of Doar Hayom, the Hebrew daily edited by Ze’ev Jabotinsky, to rally Palestine’s Jews around the cause. “An appeal to the people of Israel in all parts of the world,” published on August 12, implored the Jewish people to “Wake up and unite! Do not keep silent or rest in peace until the entire Wall has been restored to us!” The statement called on Jews around the world to form their own branches of the committee and to protest outside British consuls in their countries. “Move heaven and earth at the unspeakable and unprecedented injustice and oppression which tends to rob a live nation of the last of its relics. . . . Those of us who are here will not rest until that relic which has always been ours, which had been sealed with the blood of scores of thousands of our children through two millennia and which has absorbed the tears of Israel for 2,000 years, has been restored to us.”

The next day, David returned to the Wailing Wall to pray. Already in a daze from fasting, he watched, mesmerized, as 300 young Jewish men and women marched to the wall, calling for the restoration of the Western Wall as a Jewish holy site. Carrying the blue-and-white Star of David flag that would become Israel’s national flag, they chanted, “The wall is ours,” and vowed “to sacrifice all for the Western Wall.” After observing two minutes of silence, they sang “Hatikvah”—The Hope—an ode to the 2,000-year-old longing for Jerusalem that would

become Israel’s national anthem:

Our hope is not yet lost

It is two thousand years old

To be a free people in our land

The land of Zion and Jerusalem.

Many of the marchers were members of Betar, a paramilitary youth movement founded by Jabotinsky. It drew its name from an ancient fortress in the Judaean Mountains where Jewish rebels seeking an independent Jewish state took their last stand against the Romans. Inhabited since the Iron Age, Betar was the last stronghold of the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

David was awestruck. In an impassioned letter home, he described how it felt to be at the Wailing Wall on the holy day that earned the place its name, at a time when Jews were once again rising up against a foreign occupier and fighting for their freedom.

“As we walked along Jerusalem’s streets, we could almost imagine the streams of Jewish blood flowing at our feet, the horrible scenes of slaughter. Jewish sages, budding youth, tender babes in their mother’s arms, all killed by the barbaric sword of the enemy.”

This letter, written on August 20, would be David’s last. It would soon become a chilling premonition. Though his words lamented the Jewish blood spilled in Jerusalem 2,000 years earlier, they were a hauntingly accurate description of what was to befall him and the Jewish community of Hebron only four days later.

By the time his letter reached Memphis, David would be gone, his life extinguished in a scene of slaughter much like the one he had depicted. What David witnessed in Jerusalem on August 15 was the drumroll to the end of his life, and the beginning of a century-long holy war. That day, the tensions that had been rising over the Western Wall for close to a year reached a point of no return.

Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini had seen the march from his own home near the Western Wall. While outwardly furious, inside he likely felt some satisfaction. This display of Jewish nationalism was precisely what he needed to rally the Muslims of Palestine behind him in his battle against Zionism and rival Muslim leaders. For months the Grand Mufti had faced criticism from his political opponents and segments of the Arabic press, with accusations of misappropriated Waqf funds, nepotism, and favoritism in his religious appointments. He was also denounced for seeking to make permanent his position as President of the Supreme Muslim Council.

Rumors quickly spread in Muslim circles and the Arabic press: the Jewish youth who marched to the Western Wall on August 15 had attacked Muslim residents, cursed the Prophet Muhammad, and raped Muslim women. None of this was true. Though the demonstration was politically provocative, it had been entirely peaceful. Nevertheless, pro-mufti activists handed out leaflets and posted flyers in towns and villages, spreading those rumors, and calling on Muslims to seek revenge.

“O Arab Nation, the eyes of your brothers in Palestine are upon you,” read a flyer signed by the Committee of the Holy Warriors in Palestine. “They awaken your religious feelings and national zealotry to rise up against the enemy who violated the honor of Islam and raped the women and murdered widows and babies.”

John Chancellor, High Commissioner of Palestine, had been on leave in London since June, leaving his deputy, Harry Luke, in charge of a country that was careening toward catastrophe. Friday, August 16, was the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad. Husseini’s Supreme Muslim Council organized a march to the Wailing Wall “for the defense of Al-Aqsa against the Jews.”

When Luke got word of the demonstration that morning, he phoned the mufti to report to his house for an urgent meeting. Luke asked Haj Amin to call off the demonstration. With the march planned for that afternoon, the mufti told Luke, it was too late to cancel it, but he could ensure it remained within Waqf property. Luke was satisfied with that response. Perhaps he had forgotten that the Wailing Wall was Waqf property.

Luke would later testify that if the British had banned the demonstration, the Arabs “would have killed every Jew they could get hold of,” and the British Mandate government “would have been wiped out.”

By the time Haj Amin arrived at Al-Aqsa, 2,000 men had already spilled out of the mosque following afternoon prayers. They descended to the Western Wall through the new door the mufti had built for that purpose. Led by the sheikhs of Al-Aqsa, the mob cheered, “Allah is the greatest!” and “Kill the Jews!” Armed with sticks and clubs, they beat a rabbi, tore a Torah scroll, then set fire to Jewish prayer books and to the notes to God that Jews had for generations placed in the crevices of the wall’s stones. From there, they passed through the Old City and emerged onto Jaffa Road, where they killed the first Jew they found.

After the mob retreated, Jewish journalist Wolfgang Von Weisl visited the wall and collected the remains of the torn Torah scroll and prayer books. Sir Archer Cust, a senior British official, approached Von Weisl and asked him not to publish any news of the Muslim demonstration “of a character likely to inflame Jewish public opinion.” Von Weisl, an Austrian Jew who wrote for numerous German newspapers, disregarded the British officer’s request. So did the Hebrew press, which also received warnings from British officials to refrain from publishing “exciting statements about the events of that day.”

The following day, Muslims returned to the wall to attack worshippers and interrupt Sabbath prayers. Jerusalem descended into a spiral of mayhem. On Saturday, August 17, a group of Jewish teenagers was playing soccer in a field near Lifta, an Arab village on the outskirts of Jerusalem, when they accidentally kicked their ball into a family’s tomato patch. Avraham Mizrachi, a 17-year-old Jewish boy, went to retrieve the ball from an Arab girl. Mizrachi was stabbed by an Arab man. A brawl broke out between the groups, leaving two dozen bruised and bloodied young Arabs and Jews. The Jewish boys proceeded to beat up random Arab residents of the neighborhood, stabbing one young man in retaliation for Mizrachi. Attacks on Jews by Arabs occurred throughout the day in various parts of Jerusalem.

The next four days saw a series of attacks and counterattacks, with Jews roughing up Arabs as they walked through Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarters, and Arabs attacking Jews when they entered Arab neighborhoods. The young Arab man who was stabbed by Jews recovered from his wounds. Avraham Mizrachi did not. Following his death on August 20, his funeral the next morning morphed into a protest against the British and the Arabs. Masses of Jews joined the funeral procession, which the police tried to restrict to Jewish areas, hoping to avoid further clashes. The mourners took their time, walking slowly through the city over the course of three hours toward the cemetery. When they tried to break through a line of British officers led by Douglas Duff, the police charged at them with clubs, beating dozens of mourners and wounding nearly thirty of them. Amid the mayhem, Mizrachi’s body fell to the ground, uncovered from its shrouds.

The following day, British officials were in a frenzy of meetings, trying to calm the passions raging in Jerusalem’s streets. They met with Zionist leaders, who issued appeals to the Jewish community to remain calm and refrain from political demonstrations. They met with Muslim leaders, who promised to tone down the incendiary speeches that were being delivered at mosques. If those messages were delivered, they made little difference.

Around midnight on Wednesday, August 21, a band of 100 Arabs on horseback approached the Jewish neighborhood of Yemin Moshe, a hilltop of cobblestone alleyways and stone homes overlooking the Old City. Police rushed to the area and the would-be attackers retreated. The following day, a group of Jewish worshippers was stoned at the Wailing Wall. A Russian Christian mistaken for a Jew was severely beaten in the Old City. Thirty miles north of Jerusalem, a 70-year-old Jew was stoned and robbed while walking through the city of Nablus.

Rumors were circulating in the Jewish and Arabic press that the mufti had called for masses of Arabs to gather at Al-Aqsa that Friday, August 23, to defend Islam from the Jews. Jewish officials who met with Acting High Commissioner Luke on August 22 asked him if the government would disarm anyone who came to Jerusalem the next day carrying clubs or heavy sticks. Such a step would be dangerous, Luke said, as “it might infuriate people who were carrying sticks without any evil intention.” Luke assured them that he had arranged for “calming speeches to be made in the mosques on the following day,” and that he had ordered armored vehicles to be sent from Transjordan.

Solomon Horowitz, a member of the Palestine Zionist Executive, suggested that Luke hold an emergency meeting between Jewish and Muslim officials to call for a truce. On Thursday evening, August 22, Luke welcomed three members of the Zionist Organization and three representatives of the Palestine Arab Executive in his Jerusalem home. The goal was to issue a joint proclamation to the country’s Arabs and Jews. The hours-long gathering over tea was friendly. Agreements were made on a statement calling for peace. The proclamation, drafted by Zionist Executive member Isaiah Braude, read: “We, the undersigned representatives of the Moslem and Jewish supreme institutions, wish to inform both the Jews and the Moslems that at a joint meeting we came to the conclusion that the present excitement among the Moslems and the Jews is chiefly due to a misunderstanding. We are convinced that by goodwill the misunderstanding can be cleared up. For this reason, we demand that both the Jews and the Moslems should do their utmost to attain peaceful and quiet relations. We all deprecate any acts of violence and appeal to everyone to assist their supreme institutions in the sacred work of obtaining peace between both nations.”

When it came time to sign the document, the Arab representatives refused. According to the British account of the meeting, they “would not agree that the time was ripe for the signature of one document by prominent persons of the two races.” Before leaving Luke’s house around 10:00 that night, the men agreed to reconvene four days later, on August 26. By then it would be too late for too many.

Arab villagers armed with sticks and knives converged on Al-Aqsa that night. The colonial police force was disastrously unprepared. There were 171 British officers in all of Palestine, and no military force to speak of. Of the 1,500 Palestinian policemen, the vast majority were Arabs. Many either joined their brothers in arms or refrained from using force out of fear of becoming targets for vendettas. The country’s head of police, Arthur Mavrogordato, was on vacation in England. The British had six armored cars and no more than six workable airplanes. In Jerusalem, just 72 policemen were stationed across the entire city, and none in the Old City were armed.

The Haganah, however, had been preparing for this moment. Commanders of the underground Zionist militia had sensed the inevitability of riots weeks earlier. Throughout that night, armed Haganah men and women patrolled the Jewish neighborhoods of Jerusalem.

In early August 1929, 17-year-old Aharon Chaim Cohen stood at a meeting of Haganah fighters in Jerusalem as his officers announced that an attack on Palestinian Jewry was imminent. “Who is ready to serve as a spy among the Arabs?” a commander asked the group of volunteers. Cohen was the only one who stepped forward.

Born in Jerusalem, Cohen was one of the only Mizrahi members of the Haganah. His father was from Iran. His mother’s family hailed from Morocco. Cohen was fluent in Arabic, and lived in the mixed Arab-Jewish neighborhood of Musrara. He was told to report to Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, a senior member of the Haganah and the Zionist Executive who would go on to become Israel’s second president. Ben-Zvi instructed Cohen to quit his job at the printing shop where he worked to support his family, and to become a full-time spy. This teenage Palestinian Jew may well have been the first spy for the unborn Jewish state that would come to enlist many like him.

After securing a keffiyeh and abaya, the traditional Arab headdress and robe, Cohen blended in seamlessly. He went by Ibrahim Da’er, taking the surname of a large Muslim clan from Musrara. His first two weeks were spent wandering the streets of Jerusalem’s Muslim neighborhoods, perfecting verses from the Quran, practicing Islamic prayer customs, and becoming a familiar presence at Al-Aqsa Mosque. He provided reports to Haganah headquarters, detailing the storage rooms of weapons he discovered at the mosque, the sermons delivered there, and rumors he heard about plans to strike Jewish communities in and around Jerusalem.

The night of August 21, he was stopped by a group of about a dozen armed Arabs just outside the Old City. “Hands up,” they ordered him. “What is your name, and what are you doing wandering the streets at this hour?”

“My name is Ibrahim Joz Da’er,” Cohen told them. “I’ve been sick for a few days, and the doctor told me to take long walks at night for fresh air.” Still suspicious, the armed men tested him by ordering him to recite the opening prayer of the Quran. He did so calmly and to perfection. “Go home, and don’t be seen here again until next week,” they told him.

As he walked back to the Old City, realizing that he could have been killed, Cohen fainted. He woke up to the faces of Avraham Ikar, a veteran of the Jewish Legion who was now head of the Haganah’s Old City battalion, and Shoshana Gershonovitz, a leading female member of the Haganah who would later establish the women’s unit. After finding Cohen unconscious in a dark alleyway, they brought him to the hospital.

On Thursday, August 22, Yosef Hecht, the head of the Haganah, sent Cohen to Hebron with another Haganah member, Saadia Kirschenboim, to assess the city’s security needs. Their first stop was the Anglo-Palestine Bank to meet with its manager, Eliezer Dan Slonim, the well-known pillar of Hebron’s Jewish community. Cohen asked Slonim to gather the city’s Jewish leaders. He had an important message to relay. Slonim agreed and invited various rabbis and elders, including his 49-year-old father, Chief Ashkenazi Rabbi Yaakov Yoseph Slonim, and Meir Franco, the 63-year-old Chief Sephardic Rabbi.

Gathered in the bank, Cohen and Kirschenboim told the men that the Jews of Hebron were in danger of an impending riot. The Haganah wished to send reinforcements to protect them. The young spy presented two options: the Haganah would either send a group of fighters with weapons to safeguard the city’s Jews, or they could transfer the Jews from Hebron to Jerusalem until it was safe to return.

The leaders of Hebron’s Jewish community were unanimous. “Neither this nor that is necessary,” said Eliezer, an imposing figure who stood more than 6 feet tall, with suntanned skin and dark brown eyes. “No harm will come to the Jews of Hebron,” he insisted, owing to the warm relations that had prevailed between them and their Arab neighbors. The rabbis echoed Eliezer, assuring Cohen and Kirschenboim they had nothing to fear. The Arabs of Hebron were their friends.

Cohen abruptly left the meeting and walked out of the bank and into a Jewish home nearby, where he changed into his alias, Ibrahim Da’er. Dressed in his abaya and keffiyeh, he went to the market. After walking around for a while and finding nothing out of the ordinary, he entered a busy café and took a seat. Soon after, a man came in and invited four other patrons to the home of Sheikh Taleb Marka, an associate of the Grand Mufti who represented Hebron in the Palestine Arab Executive and led Hebron’s Muslim Association. Two of the men returned a few minutes later and summoned another customer at the café to the sheikh’s house. Cohen returned to the market, asked someone where Sheikh Marka’s house was, and walked in.

Marka, whose black beard was peppered with white hair, was telling the men seated around him about the Jewish plot to conquer Al-Aqsa. Once the Jews of Jerusalem had seized it, Marka explained, the Jews of Hebron planned to conquer Ibrahimi Mosque—the Tomb of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs. “The Jews who live amongst us and nursed from our mothers’ milk, it is they who will betray us more than the Moscovites,” said Marka, using the derogatory term for Jews who had come to Palestine from Eastern Europe. “It will be a great deed to slaughter them first.”

Cohen returned to the Jewish Quarter, changed back into his usual clothes, went to the bank, and told the Jewish leaders who were still gathered there what he had seen and heard. “Please,” he begged them, “allow a group of Haganah fighters to come here and protect the Jews of Hebron.” Still they insisted there was no need for armed Jews in Hebron. The Haganah’s presence would do more harm than good, they argued. They invited several Arab leaders of Hebron to the bank to make their case. “Even if all the Jews of Palestine are killed, not a hair will fall from the head of a Jew in Hebron,” vowed one of the sheikhs. Eliezer Slonim asked Cohen and Kirschenboim to leave. That day, Cohen met with Ben-Zvi and gave him what he called a “black report” on the situation in Hebron.

Shortly after midnight that night, Eliezer awoke to a knock at his front door. He pulled himself out of bed and opened the door to find a group of unexpected visitors: twelve members of the Haganah and their suitcases. Dressed in civilian clothes, their bags were packed with guns, bullets, and explosives. There would soon be an attack on the Jews of Hebron, the militants told Slonim. They had come—Baruch Katinka, nine young men, and two young women—to defend the community.

Slonim, tired and frustrated, brought the group into his house and proceeded to scold them. “If there was a need for men and weapons, I would request them myself!” he shouted. “There is no need because the Arabs won’t raise a hand against us. On the contrary, new faces in Hebron will only provoke them.”

Then came another knock at the door. Two Arab policemen entered the house and told the visitors to come to the police station. Ten of them followed, while two managed to stay at Slonim’s house with the suitcases of weapons. Arriving at the station, the Haganah fighters were met by the British Chief of Police, Raymond Oswald Cafferata, who was wearing his pajamas.

Born in Liverpool, 32-year-old Cafferata had joined the Palestine Police in 1921. Recruited from the Black and Tans, British reinforcements for the Royal Irish Constabulary who were known for their brutality during the Irish War of Independence, Cafferata had just been assigned to Hebron. Since his arrival on August 2, he had barely scratched the surface of the place and its people. He had met with just a few of the local Arab leaders and hadn’t yet gotten to know the city’s Jewish community. The only Englishman stationed in Hebron, Cafferata commanded a paltry force of 33 constables, nearly half of them elderly or in poor shape. All but one of the policemen were Arabs.

“Who are you and what are you doing here?” Cafferata asked the group of Haganah men and women at the station. They had come for a hike, they told him. It was a pitiful cover story considering they had arrived well after dark and tensions in the country were worse than they had ever been. Like Slonim, Cafferata was out of patience. Now was no time for hiking, he lectured them. “Go back to Jerusalem at once,” he commanded. And so they went, leaving Hebron’s Jews to defend themselves with nothing more than their prayers.

Slonim was the only Jew in Hebron with a gun. On Friday morning, he told the two Haganah men who had stayed at his house with their suitcases to

drive back to Jerusalem as well.

This was not the Haganah’s first foray into Hebron. In 1928, Haganah commander Yaakov Pat had paid a visit to the Hebron Yeshiva. He met with a group of students and asked them what they would do if Arab riots broke out in Hebron. “Without a doubt, we would defend ourselves,” they told him.

“How would you do that if you don’t have the necessary training?” he asked.

“With the help of God,” they said.