Every morning, Yiscah Smith steps into her garden — a quiet pocket of flowers and shade tucked into a narrow alleyway in Jerusalem’s scenic Nachlaot neighborhood — and speaks to God.

“Whatever I say today probably is a little different from what I said yesterday, and maybe it will be different tomorrow, because my experience with God is by nature always changing,” Smith said. “What remains my anchor is that I can depend on it.”

Smith, an educator and activist who teaches at the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, met with the Times of Israel to discuss her latest book, “Planting Seeds of the Divine: Torah Commentaries to Cultivate Your Spiritual Practice,” published last month by the Jewish Publication Society.

The book stems from monthly Shabbat morning gatherings Smith, 74, has held in the garden for the past eight years, and contains spiritual lessons and practices divided across 47 chapters covering the Torah’s 54 weekly portions, including several double portions.

“I feel closer to God in nature than I do in a synagogue,” she said. At the gatherings, she added, “I share a teaching, we sing a lot, we meditate, I bring people to contemplative practices, and we have a potluck lunch.”

Over the years, participants often asked if there was a book she could recommend for those interested in engaging in similar practices at home.

“Planting Seeds of the Divine” offers exactly that — a guide to integrating textual study and spirituality, echoing the intimate gatherings she’s cultivated in her garden.

For each chapter, the author chooses one or more verses from the respective portion that she associates with a specific middah (character trait or virtue). She then offers a concise explanation of where the verses appear in the biblical narrative before introducing selections from two types of rabbinic commentaries. The first features Jewish sources from centuries or millennia ago, including the Talmud and medieval commentators such as Rashi, Ibn Ezra and Sforno. The second section focuses on Hasidic and neo-Hasidic masters, as well as Smith’s personal interpretations.

Each chapter concludes with a specific spiritual practice, inviting readers, for example, to reflect on themselves, focus on their breathing or meditate.

Smith’s favorite chapter is the first, on Bereshit, the portion that begins the book of Genesis, which she associates with the middah of “the need to connect with others.”

“I believe that the current spiritual malady in the world is loneliness,” she said. “We have a need to connect. When we don’t, it’s as if I’m thirsty and I don’t fulfill the need to drink. I’ll get dehydrated.”

The chapter begins with two famous verses from the creation story in Genesis’ opening chapters.

“And God created humankind in the divine image, creating it in the image of God — creating them male and female,” the book’s translation reads. “The Eternal God said, It is not good for the Human to be alone.” (Gen. 1:27, 2:18)

Smith writes, “Through a spiritual lens, the purpose of all of Creation was, and continues, to bring and reveal relationship, closeness, and connection — with oneself, with God, with other human beings, and with all of God’s creations.”

She then encourages the reader to envision an ideal spiritual path for their own life.

“Seeing it as a physical path, visualize yourself as a curious hiker,” she writes. “You’ve received the opportunity to explore any landscape of your choice. […] As you meet fellow travelers moving along their own paths, envision that at any intersecting point, the sense of connection enhances your own joy.”

She goes on to ask, “How does it feel not to connect—and then to connect?”

For Smith, the question is hardly theoretical: She was in the middle of writing the book on October 7, 2023, when thousands of Hamas-led terrorists swarmed into Israel, killing some 1,200 people, wounding thousands and taking more than 250 hostages.

Smith feels that the attack — the worst Jewish catastrophe since the Holocaust — came after a period of strained relations, or broken connections, between different parts of Israeli society, particularly over the government’s judicial overhaul.

“I sense intuitively that there’s a direct connection between that event and everything that led up to it,” she said. “We could have all done better.”

And like many Israelis, she had personal connections to October 7.

“I have a granddaughter who is an officer in a search and rescue unit and who was at the Zikim base, another who is dating a musician who was at Nova,” she said, referring to a military base and a music festival that were among the bloodiest sites of the attack.

“Like everybody else, I was traumatized,” she said.

“Planting Seeds of the Divine” follows Smith’s first book, a 2014 memoir titled “Forty Years in the Wilderness: My Journey to Authentic Living.”

Smith, who is a transgender woman, was raised in a largely non-observant Jewish family in 1950s New York and gravitated toward the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement at university, ultimately becoming a rabbi and father of six in Jerusalem’s Old City. In the 1990s, in a deep crisis, Smith left that life and Judaism behind. After age 50, she transitioned and came to re-embrace Judaism.

“For the past 20 years, it’s been so exciting,” she said. “I get up every morning so excited to be Jewish.”

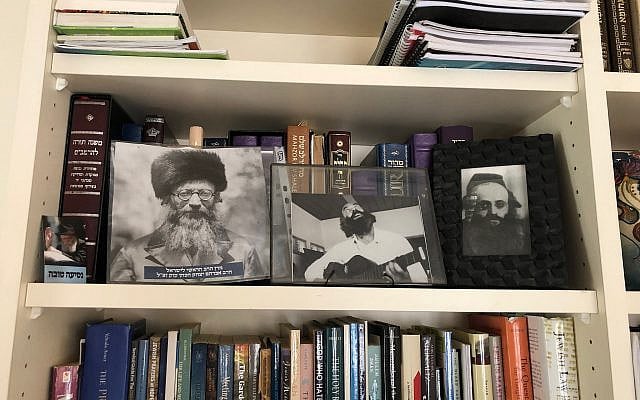

Smith credits her grounding in traditional Jewish knowledge to the years she spent immersed in ultra-Orthodox frameworks.

“Being a believer in divine providence, I have no regrets that I went into that world,” she said. “I was glad I went in, and I’m more glad I left because I took with me a discipline of learning that, unfortunately, many liberal people I connect with more now don’t hold as an important value.”

The idea of writing another book remained in the back of Smith’s mind until a 2022 trip to Warsaw. There, she visited the gravesites of relatives of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, known as the Piaseczner Rebbe, who was killed in the Holocaust.

“His teachings brought me back to my soul, to God, to Judaism and the world, the spiritual dimension of the world,” she said. “I knew I wouldn’t see his grave, as he was murdered in a death camp and buried in a mass grave. But his mother, his wife and son were buried there, and that was the closest I could get to this presence.”

As she was standing in the cemetery, Smith felt a calling.

“On his wife’s gravestone, the rebbe honored her as his chavruta, study partner, who learned with him every day and edited all his manuscripts,” Smith explained.

“It was so radical for a Hasidic master to give such public acknowledgment to his wife,” she added. “As I was standing there, I heard a voice telling me to start writing my book. As if the woman told me, ‘You admire what I did with my husband. Now it is your turn’.”

The book aims to help readers across the Jewish religious spectrum connect with the religion’s spiritual dimension.

“I wrote this book for Jews with a more traditional background who are interested in spiritual teachings and for Jews who are sensitive to spiritual teachings but do not have a background in traditional commentaries,” Smith said.

Smith also hopes the book will serve as a resource for Jewish leaders, rabbis, teachers, educators, chaplains and therapists, as well as a growing population of students and researchers studying spirituality in universities worldwide.

“I also wrote it for non-Jews, gentiles who are spiritually sensitive, including theologians,” Smith said, explaining that she frequently welcomes non-Jewish participants to her classes.

“In my classes, in the lectures I give, many have come to me, Jews and non-Jews, and told me the same thing: ‘I did not know that Judaism had this.'”