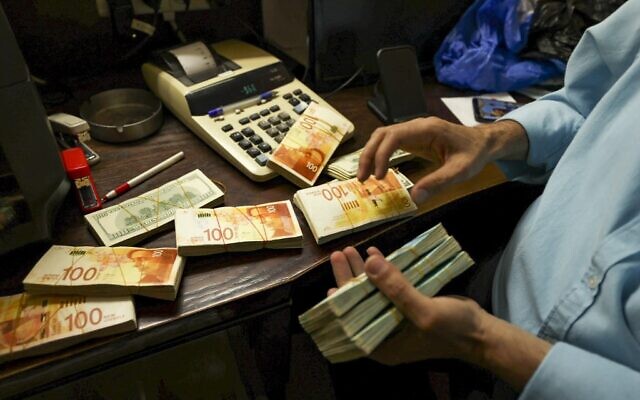

After selling a car a couple of weeks ago, Muhammad took the NIS 10,000 ($3,000) check to his bank — but he couldn’t make the deposit.

“If you just want to deposit money in the bank, they won’t take it,” said Muhammad, a father of three from Ramallah who asked to remain anonymous to protect his privacy. “Even if it’s for a transaction or a check that needs to be deposited, it’s hard.”

So he waited, check in hand, depleting his account until he was in overdraft. Then he tried to deposit the money again.

“They saw I was in the red,” Muhammad recalled. “And then when I came in and said, ‘I have an NIS 10,000 check,’ they said, ‘Oh, you do? Then give it to us.'”

Such experiences have become common across the West Bank, where an Israeli policy that dates back more than 30 years has given Palestinian banks a buildup of surplus shekels. That, in turn, has led the Palestinian Authority to place a ban on accepting any more — a decision that is hobbling the local economy, which runs on the Israeli currency and is intertwined with the Israeli market.

The glut of shekels has had concrete consequences across the territory and it has created a severe liquidity crisis in a region already feeling economic strain from the war in Gaza and the PA’s own chronic financial problems.

“Palestinian imports and exports are primarily to and from Israel, and they are conducted in shekels,” Sameh Al-Ataout, an economics expert at An-Najah University in Nablus, told The Times of Israel. “Many Palestinians work in Israel and earn shekels. More than 2 million Arab citizens of Israel enter the Palestinian territories each year, they shop, they eat — all in shekels.”

The roots of the problem go back to the Oslo Accords, the 1994 Israeli-Palestinian treaty that created the PA. The accords’ economic annex, known as the Paris Protocol, designates the shekel as the official currency of the Palestinian territories. Palestinian banks were to rely on the Bank of Israel to exchange currency, primarily into US dollars and Jordanian dinars.

While the protocol did not specify a cap on how much currency could be exchanged, it did state that “to avoid undesirable fluctuations in the foreign exchange rate, monthly ceilings for conversion will be agreed upon in annual and semiannual meetings” between the Bank of Israel and its counterpart, the Palestinian Monetary Authority.

Also created in the 1994 Oslo Accords, the Palestinian Monetary Authority serves as the regulatory body overseeing the banks operating in the Palestinian territories — most of which were established long before the PA was founded.

In practice, for nearly three decades, Israel has imposed an informal currency exchange limit of NIS 18 billion per year ($5.4 billion), or NIS 4.5 billion ($1.35 billion) per quarter. This number has remained static despite considerable inflation — and Palestinian economic expansion — since the mid-1990s. The PA’s GDP has grown from $5 billion in 2005 to $17 billion in 2023, according to the World Bank.

“The Palestinian economy has grown over the past 25 years. There’s been real growth,” Al-Ataout said. “This ceiling no longer matches the scale of the economic relationship between the Israeli and Palestinian sides.”

The Palestinian Monetary Authority said recently in a public statement that Israel had placed “restrictions and ceilings… on money transfers.” In other words, it stopped converting shekels out of concern that the annual cap would be exceeded.

That policy means that Palestinian banks now have growing piles of shekels they can’t convert. On May 29, the Palestinian Monetary Authority made an open-ended announcement that the banks would stop accepting shekels.

In response to a request for comment, the Bank of Israel told The Times of Israel: “There has been no change in instructions or directives regarding these matters.” Israel’s Finance Ministry spokesperson similarly stated that “there has been no change in instruction on this matter from the Finance Ministry.”

The shekel ban is exacerbating an existing economic crisis in the West Bank. A sharp reduction in Israeli work permits for Palestinians following the Hamas-led October 7, 2023, attack has deprived the territory of a major source of income. Now, the ban means Palestinians are facing frozen bank accounts, a black-market currency exchange and growing disruptions to daily economic activity.

“If I go to deposit a check in shekels, the bank refuses to take it — they ask for Jordanian dinars instead,” a Nablus resident who asked to remain anonymous told The Times of Israel. “If you try to exchange shekels for dinars or dollars at the bank, they won’t do it.

The Nablus resident explained that, “for the first time, a black market for foreign currency exchanges has emerged in the West Bank,” where consumers’ shekels end up losing value and are exchanged at four shekels to the dollar as opposed to the official rate of approximately 3.3.

In addition to individuals, institutions and businesses are also struggling to deposit revenues. Palestinian gas stations — where customers pay mostly in cash — have been hit particularly hard. With banks refusing to accept their accumulated stocks of shekels, some stations have had to reduce their services.

On July 2, the Palestinian Monetary Authority announced that it had resumed transferring surplus shekels from Palestinian to Israeli banks, sending NIS 4.5 billion in the third of four planned quarterly transfers for the year.

But according to Iyad Zaitawi, a senior official at the authority who gave an interview to a PA media channel, that amount is just a dent in the whole. Palestinian banks are still holding another NIS 13 billion in surplus and are still not accepting more shekels. He added that the PMA is currently trying to negotiate an increase in the annual conversion cap from Israel from NIS 18 billion to NIS 25 billion.

The PA has no practical way to create an independent currency, which would require Israeli consent and economic cooperation, something that would only be possible under a final-status agreement.

The crisis highlights Israel and the Palestinian territories’ deep economic interdependence. The two economies function as one integrated system, with a shared currency and cross-border trade.

According to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, the Palestinian Authority was Israel’s third-largest export market in 2022, accounting for 0.7% of Israel’s GDP in the most recent figures available. Thousands of Arab Israelis study, visit and stay in the West Bank, and tens of thousands of Palestinians work in Israel, primarily in construction and agriculture.

But recently, Israel has taken steps to limit its economic coordination with the PA. Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who oversees the exchange policy, has voiced hostility toward the PA. He has also previously frozen PA tax revenues, which Israel collects, in retaliation for diplomatic developments or Palestinian policies the Israeli government opposes.

Last month, just hours after the United Kingdom and other countries sanctioned Smotrich and National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir for “inciting violence against Palestinians,” Smotrich ordered the cancellation of key protections that enable cooperation between Israeli and Palestinian banks. Specifically, he moved to revoke a government guarantee (known as the “indemnity”) that shields Israeli banks from liability when working with Palestinian institutions.

For that decision to take effect, Smotrich must formally sign it, and the security cabinet must approve it. Neither step has so far occurred. (Smotrich’s office did not respond to a request for comment.)

“Today, the Israeli finance minister’s goal is to dismantle the Palestinian Authority economically,” Nidal Foqaha, director of the Geneva Initiative, a group promoting a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, told The Times of Israel.

“If there were a different government in Israel, we wouldn’t be in this situation,” Foqaha said. “Israel has no problem accepting shekels — it’s their currency.”