Syria’s interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa has in six months established himself internationally and had crippling sanctions removed, but he still needs to rebuild national institutions, revive the economy, and unite the fractured country.

It has been half a year since an Islamist-led coalition led by the new leader toppled longtime strongman Bashar al-Assad on December 8.

After ousting Assad, Sharaa has had to navigate four political entities, each with its own civil, economic, judicial and military organizations.

There is the central government in Damascus, the incumbent president’s former rebel authority in the northwest, Turkey-backed groups in the north, and a Kurdish-led autonomous administration in the northeast.

Radwan Ziadeh, executive director of the Washington-based Syrian Center for Political and Strategic Studies, said that creating relative stability in this fragile context was “a significant accomplishment” for Sharaa.

But guaranteeing the success of the five-year transitional phase will be “the most difficult challenge,” Ziadeh said.

The new authorities’ ability to maintain stability was cast into doubt when deadly sectarian clashes hit the Syrian coast in March and the Damascus area the following month.

Some reports claimed more than 1,700 people were killed in the coastal violence, mostly members of the Alawite minority to which Assad belongs.

Near Damascus, pro-government forces clashed with local militias from the Druze minority community, after an audio clip circulated on social media of a man criticizing Islam’s Prophet Muhammad.

Amid the violence, Israel launched a series of airstrikes that it framed as a warning over threats against the Druze, a minority group with communities in Syria, Lebanon and Israel.

The treatment of minorities remains “one of the greatest internal challenges,” Ziadeh said, as “building trust between different components requires great political effort to ensure coexistence and national unity.”

Badran Ciya Kurd, a senior official in the Kurdish-led administration in the northeast which seeks a decentralized Syrian state, warned against “security and military solutions” to political issues.

The transitional government should “become more open to accepting Syrian components… and involving them in the political process,” Kurd told AFP, calling for an inclusive constitution that would form the basis for a democratic system.

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio warned last month that Syrian authorities could be weeks away from a “full-scale civil war” due to the acute challenges they faced.

Sharaa’s “greatest challenge is charting a path forward that all Syrians want to be part of, and doing so quickly enough without being reckless,” said Neil Quilliam, associate fellow at the Chatham House think tank.

There are pressing security challenges, with kidnappings, arrests and killings sometimes blamed on government-linked factions.

Assaults on nightclubs in Damascus have sent a chill through the cosmopolitan capital, compounding fears that personal freedoms could shrink under the rule of the former Islamist rebels.

Recent bouts of sectarian violence have also raised concerns over Sharaa’s ability to keep radical fighters among his forces’ ranks in check.

Six foreign fighters have been promoted in the new defense ministry, sparking international criticism. A Syrian source with knowledge of the matter told AFP, however, that Damascus had told the United States it would freeze the promotions.

Washington initially said it wanted foreign jihadists to leave the country.

But American envoy to Syria Tom Barrack said recently that the US has given its blessing to a plan by Sharaa to incorporate thousands of foreign jihadists who are former rebel fighters into the national army, provided that it does so transparently.

Washington also wants the Syrian government to take control of Kurdish-run prisons and camps where thousands of suspected Islamic State group jihadists and their relatives are detained, but Damascus lacks the personnel to manage them.

Sharaa is leading a country battered by 14 years of civil war, with its economy depleted, infrastructure destroyed, and most people living in poverty.

Under the new authorities, Syria has seen an increased availability of fuel and goods, including certain fruits whose import had previously been near impossible.

After Western governments lifted many sanctions, Sharaa’s priority now is fighting poverty in order to “stabilize the country and avoid problems,” according to a source close to the president.

Economist Karam Shaar said that beyond political stability, which is essential for economic growth, other obstacles include “the regulatory framework and the set of laws necessary for investment, which unfortunately seem vague in many parts.”

Authorities have said they were studying legislation that could facilitate investments, while seeking to attract foreign capital.

Rehabilitating Syria’s infrastructure is key to encouraging millions of refugees to return home, a major demand from neighboring countries and others in Europe.

Syria must also determine its relationship with neighboring Israel.

It was reported last week that Israel and Syria are in direct contact and have in recent weeks held face-to-face meetings aimed at calming tensions and preventing conflict in the border region between the two longtime foes. Sharaa has acknowledged indirect talks aimed at calming tensions in the border region.

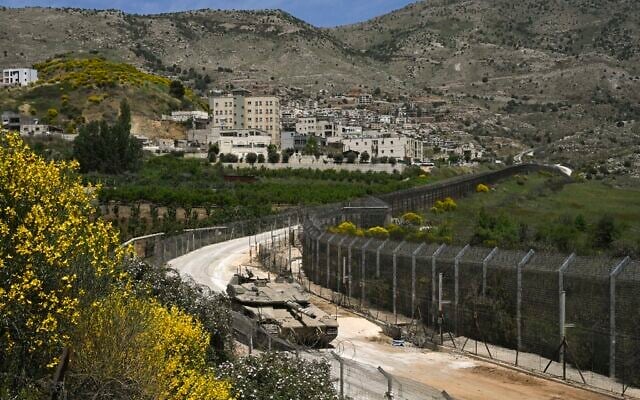

Since Assad’s fall, Israel has bombed what it says are military targets across the country to neutralize threats, and Israeli ground forces have entered southwestern Syria, where they are currently stationed in a number of outposts in a buffer zone in the Golan Heights.

The Jewish state has also cautioned against swift recognition of the new government in Syria, expressing deep skepticism about Sharaa.

On Friday, Israel carried out airstrikes near the coastal Syrian city of Latakia — its first attacks in the country in nearly a month — targeting what Israel said were weapons depots used to store anti-ship missiles. Syrian state media said one civilian was killed.

The US’s Barrack described the long-standing conflict between Syria and Israel, who have technically been at war since Israel’s creation, as a “solvable problem” through dialogue, proposing a “non-aggression agreement” between them.

But according to Quilliam, Damascus is “light years away from considering normalization” with Israel.

Times of Israel staff and Reuters contributed to this report.