On February 21, 2025, a few hours before Omer Shem Tov was set to be released after some 500 days in captivity in Gaza, his mother Shelly shared a clip on her Facebook page featuring some moments of a Shabbat she had attended at a hotel in Jerusalem a year before.

“Nothing happens by chance: everything is from Him,” Shelly wrote. “Exactly one year ago, on the eve of the Shabbat featuring the weekly Torah portion of Mishpatim, we were invited to a Shabbat organized for hostage families.

“It was the first Shabbat in my life that I observed according to halacha [Jewish law],” she continued. “On that day, I took upon myself to keep Shabbat, and since then, I have kept Shabbat throughout the year. And more than I kept Shabbat, Shabbat kept me. And God willing, on this Shabbat, I will get to hug my Omer exactly one year later.”

Shem Tov was taken captive by Hamas terrorists at the Nova festival with his friends Maya and Itay Regev on Saturday, October 7, 2023.

When the Regevs were released in the ceasefire agreement of November 2023, Itay, who had been kept with Omer, revealed that his friend had started to observe Shabbat as much as he could. Shem Tov would use a piece of toilet paper as a kippah head covering and avoided turning on the flashlight that was his only source of light on Friday nights. He also hoarded a half-bottle of grape juice they had once been given, taking a sip every week after reciting the Kiddush, which sanctifies the Shabbat, according to details Shem Tov himself shared in interviews after his release.

Although the Shem Tovs observed some Jewish traditions before Omer was kidnapped, up until that moment, the family had identified as secular. While Omer was in Gaza, the family in Israel increasingly adopted Jewish practices during the 17 months of his ordeal.

The Shem Tovs are not an isolated case.

The January-February 2025 ceasefire deal between Israel and Hamas saw 23 Jewish hostages from October 7 released alive, in addition to two Israeli men with mental health issues who had voluntarily entered Gaza years earlier, five Thai hostages, and eight bodies.

In those weeks of hope and chaos, as the country held its breath, witnessed hostages come home, and mourned over the eight who were brought back in coffins, many of those who returned revealed how, in captivity, they found a new spiritual path, including some individuals who came from completely secular backgrounds.

At least 12 of the 23 shared that they had discovered new meaning in Jewish rituals while they were in Hamas’s tunnels.

According to two clinical psychologists who spoke with The Times of Israel, the phenomenon is not surprising.

Dr. Einat Yehene, head of Rehabilitation at the Health Division in the Hostages Families Forum, a researcher, clinical neuropsychologist, and expert rehabilitation psychologist, said it is not uncommon for people’s relationship with faith to change as a result of dramatic, life-changing events.

“This is something that I have witnessed throughout my years of experience working with people in all kinds of life-changing events, traumas like car accidents, severe injury, death, and other losses,” she said.

“People either become more religious or more secular as they experience a faith crisis, because they come to believe that if there were a God or any protecting power in this world, this would not have happened,” said Yehene.

Yehene noted that from what she has seen in the cases of the hostages and their families, many more have found faith than lost it.

“This situation [of captivity] causes the hostages and their families to grapple with an overwhelming sense of helplessness,” the psychologist said. “When people feel that they are powerless, they externalize the power and feel more in control by believing that, if it’s not me, there must be somebody else who will fix the situation.”

Yehene said that the idea of a higher power can also help hostages and families as they seek a meaning in the ordeal they are going through.

“People need to find meaning in traumatic events in order to be able to integrate them into their life narrative and also endure their adverse consequences,” she noted. “They need to find answers for questions like, why did this happen, why to me and not to other people, what can I learn from it.”

The psychologist explained that the idea that there is something bigger than yourself in the universe can help provide these answers.

The Shabbat attended by Shelly Shem Tov was organized by the NGO Kesher Yehudi.

Established in 2012, until October 7, Kesher Yehudi primarily focused on bringing together ultra-Orthodox and secular Israelis for study partnerships (chavrutah in Hebrew), fostering unity across societal divisions, as its founder, Tzili Schneider, told The Times of Israel in a video interview.

“We work to connect the two parts of society farthest from each other,” the mother of 11 said.

Over the years, Kesher Yehudi has connected approximately 17,000 study pairs, with 6,000 of these pairs still active.

Asked whether the program has the goal of kiruv, or “bringing close,” the Hebrew term to persuade people to become more religious, Schneider said, “There is a big purpose of kiruv, but a different kind of kiruv — bringing people together, so that they can feel close like brothers and sisters.”

Schneider explained that one of the elements that inspired her to get involved with the hostages was that one of the young men kidnapped at Nova had maintained a very strong bond with his Haredi chavruta study partner. She emphasized that the Haredi community in Israel needed to be more involved in the plight of those held in Gaza.

Schneider recalled how, at the beginning of 2024, she decided to visit a hostages family tent in Jerusalem with her friend Yaffa Deri (wife of the Sephardic Haredi party Shas’ leader Aryeh Deri).

“I met with eight or nine families, maybe some 30 people, not even one of them was Shabbat-observant,” Schneider said of her visit to the tent.

She shared how she had a back-and-forth with those in the tent and asked them, to whom were they addressing their slogan, “Bring them home now.”

“I asked them, ‘Are you talking to Sinwar, who kidnapped them?’ They said no. ‘So are you talking to [then-US President Joe] Biden?” They said that it looked like he couldn’t do it. What about Bibi [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu]? ‘Maybe.'”

Yet, the families expressed skepticism that even Netanyahu could bring their loved ones home.

“I asked them, if it was not Sinwar, not Biden and not Bibi, who could bring back the hostages,” Schneider said. “It was a very moving moment, because all the eyes and the hands pointed up to the Heavens.”

A mother whose son was kidnapped and is still in Gaza told Schneider that she believed God could save her child because, from all that she had heard about his capture, he should have died, and the fact that he survived meant that God was looking after him (50 hostages remain in Gaza, at least 28 of whom were confirmed dead by Israel).

Schneider said that, eventually, she and that mother became close friends, and at the time she spoke with The Times of Israel in March, they were talking every night.

After those in the tent appeared to agree that only God could save the hostages, Schneider proposed that the families take action “to appeal to Him.”

In her conversation with The Times of Israel, Schneider invoked the concept of hishtadlut — a form of faith that emphasizes making proactive efforts toward a goal while acknowledging that the outcome ultimately rests with God. The Jewish sages contrast this with bitachon, a mode of trust that entails complete reliance on God’s will, without taking any personal action.

“I know that the war started on Shabbat,” Schneider said she told the hostage families. “Maybe we will persuade Him by doing something to honor Shabbat.”

Schneider suggested keeping together “one Shabbat kehilchata” (according to Jewish law).

“I immediately said that I was not promising them that this would return their children, but I could promise that it was the right activity in the right channel,” she noted. “I told them that keeping one Shabbat according to Jewish law would make a big impression on God.”

After that first Shabbat, Kesher Yehudi organized several additional shabbatonim either for hostage families or Nova survivors, in addition to prayer gatherings and holiday celebrations. The events were also attended by Haredi families and youth.

“I have been so impressed with the mesirut nefesh [act of self-sacrifice] of some of those Nova survivors,” Schneider said.

“For me, Shabbat is a fun time, I don’t need self-sacrifice to keep Shabbat,” she added. “But I have seen them going without a cigarette, clinging to the walls, asking me when it is over, and I would say that even keeping Shabbat for a few hours is something important to God, but they would insist on keeping a full Shabbat to say they did something for their friends.”

Schneider also shared a story about how the mother of a hostage took part in a prayer gathering that Kesher Yehudi organized at Rachel’s Tomb near Bethlehem in the West Bank.

“She prayed for a sign of life from her son, and the following day Hamas published a propaganda video of him,” Schneider recalled. “After that, she called and said she should have prayed for his freedom instead.”

According to Yehene, fostering a sense of connection is a factor that might influence hostages’ loved ones to get closer to religion.

“They adopt all kinds of spiritual practices to maintain the bond with the hostage, to send them energy,” she said. “Sometimes, they even make all kinds of promises that if the hostage is safe and returns, they’re willing to take more practices upon themselves, like in a vow.”

Some hostages may have taken on more Jewish rituals while in captivity as a way to differentiate themselves from their Muslim captors as a survival technique, Yehene said.

“Their Jewish religious identity becomes more prominent,” she explained, because the hostages need it in response or as a shield to their embroilment with their Muslim captors.

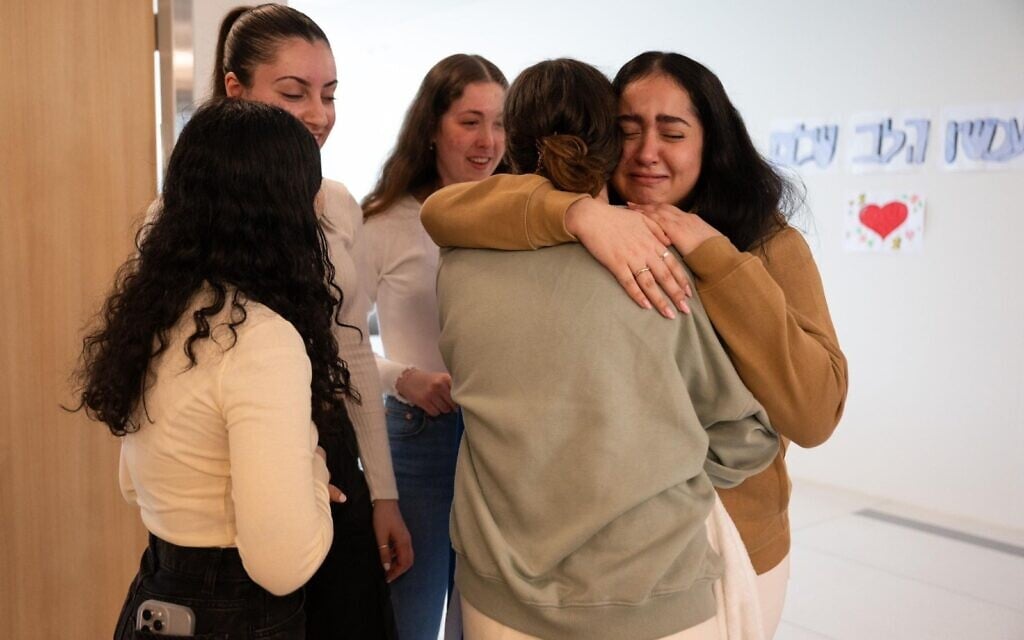

Former surveillance soldier Agam Berger is a prominent case of a released hostage who embraced her Jewish religious identity. When, shortly after she was liberated from Gaza on January 30, 2025, Berger flew in a military helicopter on her way to the hospital, she held up a sign on a dry-erase board reading “I chose a path of faith and I returned through a path of faith… There is no other than the Creator.”

Rumors had been circulating for a while about how the 20-year-old had started observing Shabbat and other aspects of Jewish law during her time in captivity. At the same time, her parents, fighting for her return, had also found new meaning in religion.

“Three weeks after Agam was kidnapped, we brought a Torah scroll to her room, to wait for her return,” her mother Merav shared during an event at the Anu Museum in Tel Aviv in May. “I thought that it was not appropriate for a Torah to just wait in a room, so we started a synagogue on the ground floor of our building, and there we prayed every Friday night and Shabbat morning.”

“Agam was kidnapped as a Jew,” she added. In Gaza, “she refused to eat meat [because it was not kosher] and did not eat hametz [leavened food] during Passover, and, at some point, she received a siddur [prayer book] and she prayed every day.”

Berger herself shared in an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal that the Hamas terrorist holding her tried to coerce her into converting to Islam.

“Our faith and covenant with God, the story we remember on Passover, is more powerful than any cruel captor,” she wrote.

According to Rabbi David Stav, from the moderate Modern Orthodox rabbinical group Tzohar, Berger’s frankness about her faith may have inspired other hostages to share their Jewish experiences, which were in turn shared eagerly by individual Israelis and news outlets.

“I think that this shows that the Israeli society after October 7 is not what it used to be before. [Jewish practices] are not considered exotic or strange but rather something that belongs to everybody,” Stav told The Times of Israel by phone.

The rabbi also emphasized that the choice of hostage families to engage in good deeds for their loved ones in danger is not limited to religious acts.

“I just met with a family last week that told me how they will just try to do good in order to strengthen their son who is in captivity,” he said. “One of the people asked me to tell the story of his son to inspire good things. He did not become observant, but he decided to be a better person.”

Stav, a frequent participant in rallies at Tel Aviv’s Hostages Square, believes that many people affected by the hostage crisis had hoped for greater support from religious Israelis — and are disappointed by their absence.

“Jewish awakening is not happening because of religious people, or because of rabbis,” he said. “It’s happening in spite of them.”

According to Yehene, for many hostages who were freed in the January-February ceasefire, engaging in Jewish practices has also in some way become part of their identity as returning hostages, especially for those who were in captivity and observed rituals together.

“The fact that many engaged together in Jewish practices is really becoming part of their united solidarity, part of their culture in captivity,” she said. “It’s almost as if they developed a language for themselves.”

Shir Siegel, daughter of Keith, who was kidnapped from Kibbutz Kfar Aza and released on February 1, shared in an interview with the Israeli Channel 14 a few weeks after his release that, in captivity, her father would recite blessings over food and the foundational Jewish prayer, Shema Yisrael, something he had never done in his life.

She added that for the first Shabbat at home, the family checked with Keith what he would be happy to have.

“I expected he’d want some dish he loves or a good challah, but he replied, ‘You know what I want most of all? A kippah and a Kiddush cup,'” she said.

The Berger and Siegel families were also among those who attended the Shabbat organized by Kesher Yehudi in February 2024.

Kesher Yehudi is but one of many religious organizations involved with the hostages and their families in different capacities.

Events and initiatives for the hostages have been promoted, among others, by Aish HaTorah and by Haredi activist Riki Sitton, who was invited to light one of the torches at Israel’s 77th Independence Day Celebration in May, in recognition of her work.

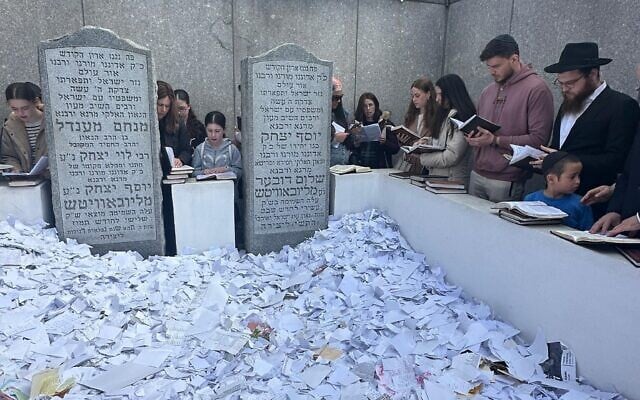

Already in November 2023, the Chabad Lubavitch Hasidic movement organized a charter flight for approximately 170 hostage family members to fly to the United States for an intense visit, which began with a stop in New York to pray at the Ohel, the resting place of the late Rebbe Menachem M. Schneerson. The trip also included the 300,000 people-strong March for Israel in Washington, DC.

Since then, hostage families and released hostages have made regular visits to the Ohel.

“I am not a religious person, but what gave me strength as I arrived in the darkest place, 50 meters underground, was to recite Shema Yisrael every day,” former hostage Eli Sharabi said as he visited the site in April in a clip shared with The Times of Israel by a Chabad spokesperson. Sharabi was released on February 8, 2025, and only then learned that his wife and two daughters were slaughtered on October 7, 2023, and that his brother Yossi had been murdered in captivity.

One of the people who helped coordinate that first November 2023 trip from Israel, specifically assisting the families with the logistics, was Rabbi Mendy Naftalin, a member of the Chabad community.

Naftalin told The Times of Israel that some three weeks after October 7, he was approached by high-tech entrepreneur and fellow Chabadnik Yossi Rabinovitz, who had been asked by a representative of the Hostages and Missing Families Forum to find a Chabad member willing to volunteer at the Forum.

“The Forum was making an effort to reach out to all sorts of people and communities in Israel, and in addition, Chabad has very strong connections abroad,” Naftalin said.

Naftalin, who was 23 at that point and had not yet been ordained as a rabbi, described starting to volunteer at the Forum when both the organization and Israel as a country were still in deep chaos after the attacks.

“As I showed up, I was trying to figure out what I could do, and I decided that I would be in touch with Chabad emissaries all over the world to bring hostage family members to visit their countries [to raise international awareness],” he said.

Naftalin recalled feeling a little out of place at the beginning, the only ultra-Orthodox person with his full Chabad black and white attire, in a place with very few religious people.

“These were kibbutznik, Ashkenazi families, really not ultra-Orthodox, but I had another way to find something in common,” he explained. “I speak a little Yiddish, and this way, I started to connect with them.”

As he met more and more relatives of the hostages, listened to their stories, and worked with them, Naftalin developed deep ties with many that he maintains to this day, he said, although he moved to Madrid a few months ago as a new Chabad emissary there.

Among other things, Naftalin said he helped organize campaigns inviting the public to perform specific mitzvot (commandments), such as lighting Shabbat candles or reciting the Shema to pray for the return of the hostages, working closely with their families.

“I had never done such things, and suddenly I had to figure out how to do it,” he said.

“I simply made a phone call, one after the other,” he added. “The biggest campaign we ran was for Bar Kupershtein, inviting people to light candles for him the Shabbat before Pesach [2024]. I remember it well because it fell on the same date as the Rebbe’s birthday.”

Yehene noted that the religious revival seems particularly significant among the hostages released in early 2025, more so than those freed in the 2023 deal. The shorter duration of captivity in 2023 — and factors such as the presence of children — may have created a different dynamic.

Yet, she emphasized that although the focus on Jewish tradition seems especially strong in the months following their release, it may still prove to be a transitional phase.

“We don’t know if this will last in the years to come,” she said.

When asked whether strengthening one’s religious identity during a crisis can be seen as a positive or negative phenomenon, Yehene explained that religious belief can play a crucial role in coping with trauma.

“Religious beliefs, or spiritual beliefs, not necessarily connected to Judaism, help people because they help them go through the daily routine; they make them feel connected to something bigger, that they are not alone,” she added. “These tools are very helpful.”

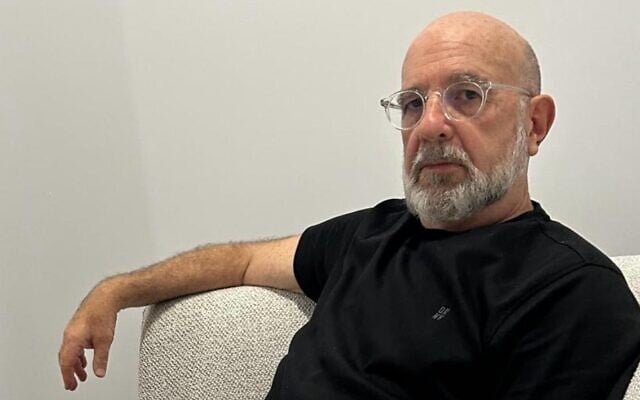

Her comments were echoed by another clinical psychologist, Dr. David Senesh.

An expert in PTSD and intergenerational trauma, Senesh shared with The Times of Israel his perspective on the newly found spirituality of former hostages and family members not only as a professional in the field, but also out of his tragic, personal experience.

A nephew of iconic Zionist poet Hannah Senesh, in 1973, Senesh was captured by the Egyptian army during the Yom Kippur War, imprisoned and tortured for 40 days. He was then released together with some 200 Israeli POWs in November the same year.

“When you’re coming out of this experience, of course, you’re in deep existential crisis,” he said. “After you take care of all the other needs, physical needs, the emotional needs, it is about how you see the world again.”

“Some people look at their own story, and that is usually the story of a miracle,” he noted. “When people are coming from this near-death experience, they have to attribute it to something, and some people build a larger story, that there is a divine intervention and there is a meaning to this.”

Senesh stressed that this has never been relevant for him personally.

“I was an atheist before, and I remain so to this date,” he said. “I consider my own rescue or survival to be a twist of fate, and that’s good enough for me.”

At the same time, he also said that beliefs can help deal with trauma.

“As a therapist, I will always go for a person to have something he can believe in; it can be a divine entity, his government, his superiors, and he can find meaning in what he did and what he went through,” he added.

Senesh said that as he pursued his career in psychology over the decades, he made a conscious choice not to work with former POWs or hostages, as he felt it would be something too close to home, focusing instead on other trauma victims, and especially children who experience domestic abuse.

Senesh and Yehene acknowledged that since both former hostages and their families find themselves in a situation of extreme vulnerability, it is crucial for anybody who interacts with them to be very careful.

“In situations like this, people are in a state of deep distress and crisis; they are very sensitive, and they can be manipulated sometimes and influenced,” Senesh said.

“In my profession, we are trying to help, but not to take any advantage or implement ideas or beliefs in their mind,” he said. “I’m not saying that religious people do that. However, there might be people who can be helping, which is great, but they also kind of have an influence on [former hostages and families’] life view. They are so fluid and they can be influenced so easily that I think that one has to be very cautious about not doing that.”

Yehene said that in her work at the Forum, she had witnessed religious values being pushed.

“There are a lot of religious entities, people who want to donate money, all kinds of religious organizations that want to be involved with the hostages,” she said, declining to name names. “There are all kinds of agendas, and sometimes the hostages are accommodating these agendas because of their own vision. This is also something we need to be aware of.”

Speaking about the hostages taken on October 7, the psychologist said that turning to religion can be positive, especially in the wake of the deep rupture in trust between them and the state.

“The collapse of the basic trust between [Israel and] the people who became hostages, the way they became hostages, the way that they were abandoned is the worst situation,” he said. “I was not abandoned, but they were. When they come out of there, it is very difficult to fix it.”

According to Senesh, religion, as something not connected to the state, can provide a space for it.

“Religion is a good place for people to be in,” he said. “You don’t have to prove anything. You don’t have to disprove anything. You can hold to it if it’s good enough. If it makes people more confident and more resilient, it does the work.”