Ameenah Qumber is a regular visitor to Israeli prisons, where she checks in on detainees serving time for terror-related offenses, the vast majority of whom are Palestinian security prisoners arrested by Israeli forces in the West Bank or Gaza.

According to Qumber, an attorney who works for the human rights group Center for the Defense of the Individual, known in Hebrew as HaMoked, conditions in prisons are “difficult.”

“We are already in a second wave of scabies that began in April,” Qumber said.

Scabies is a highly contagious skin condition caused by microscopic mites that burrow into the skin. It leads to intense itching, especially at night, and is often accompanied by a rash. The disease, almost nonexistent in Israel and the Palestinian territories before the ongoing war in Gaza, has become a growing problem in the security wings of the prison system over the past two years.

Security prisoners — those incarcerated for offenses that intentionally harm national security — are housed separately from criminal prisoners and are not eligible for many of the benefits available to the general prison population. For instance, they are typically ineligible for prison furloughs and, in most cases, cannot have life sentences commuted to a 25-year term.

“Security prisoner” is a catch-all term applied to detainees, convicted prisoners and administrative detainees who are held without charges for extended periods, without trial.

It is an administrative designation determined by the Israel Prison Service based on a range of considerations, including suspicion of offenses committed, ideological affiliation and intelligence information. In general, the term applies to any prisoner whose offenses — or suspected offenses — could potentially harm the security of the state.

As of July, 10,762 security prisoners are being held in Israel, according to figures provided by the Israel Prison Service (IPS) to HaMoked. Nearly all are Palestinians from the West Bank or Gaza. A small number — no more than a few dozen — are Arab citizens of Israel or Jewish Israelis. The IPS does not publish data disaggregated by ethnicity or nationality.

Jessica Montell, executive director of HaMoked, told The Times of Israel that those accused of a wide range of offenses fall under the categories of security prisoners or detainees.

“Military law defines a broad array of actions as ‘security offenses,’ from throwing stones at Israeli vehicles to planning and carrying out terror attacks,” said Montell. “This is in contrast to offenses that are not considered to have a ‘nationalist motive,’ which are classified as criminal rather than security-related offenses.”

She noted that being designated as administrative detainees or unlawful combatants also turns Palestinians into security detainees, without disclosing the offenses they are suspected of.

Of the 10,762 security prisoners, Israel is holding 1,419 security prisoners serving sentences imposed by the courts; 3,260 detainees who have not yet been convicted; and 3,629 administrative detainees. In addition, Israel is holding 2,454 “unlawful combatants” — a designation given by Israel to all Gazans arrested during the October 7 attack and subsequently inside the Gaza Strip during the war.

The current total of security prisoners is more than double that of October 1, 2023, just days before the Hamas-led terror invasion — which saw some 1,200 people in southern Israel slaughtered and 251 abducted to the Gaza Strip, touching off the ongoing war in Gaza — when the IPS reported 5,192 security prisoners in Israeli custody.

Qumber shared what she’s heard firsthand from prisoners.

“The prisoners I met in recent months said they were infected with scabies, began complaining, and asked to be sent to the clinic and were refused, for months,” she told The Times of Israel. “Later, they were given a single treatment: one acetaminophen pill and an ointment. Just once, over months.”

Rights groups point out that scabies was virtually unheard of in Israeli prisons before October 7, 2023. The outbreak is just one indicator of a broader collapse in prison conditions following a sharp rise in arrests of Palestinians since the start of the war, leading to increased prison overcrowding.

Both Physicians for Human Rights–Israel and HaMoked began documenting cases of scabies in late 2024, submitting complaints to the IPS and filing petitions to the Israeli High Court of Justice demanding urgent medical care.

Qumber described what she has seen in prison clinics: “The scabies spreads across the body — arms, legs, stomach, back. The marks are everywhere. In the early stages, it causes intense itching, and the prisoners scratch until they bleed. It keeps them from sleeping. Even after they start to heal, the marks remain like burn scars.”

Mohammed Abu Mukh, a security prisoner held in Ketziot Prison, submitted a sworn affidavit in May through Physicians for Human Rights–Israel, describing his scabies infection and harsh conditions in detention.

“For two months I’ve been suffering from scabies, with sores even in sensitive areas,” Abu Mukh said. “When I raised the issue, the examination in the wing was superficial, done by a medic. One time, a dentist came — who had nothing to do with it.”

“There’s no washing machine or dryer in the prison wing, and it’s impossible to wash blankets or sheets,” he added. “When they brought me summer clothes, they gave me items that had been used by other prisoners who had scabies.”

The Times of Israel reached out to other security prisoners who were infected during their imprisonment and have since been released, but they declined to speak, saying they feared they might be arrested again for doing so.

Amid growing concern from medical rights groups, the IPS stated in response to a media inquiry in March that out of the hundreds of prisoners held in Ketziot — just one of Israel’s primary security prisons — only 49 had been diagnosed with scabies, and that the situation was “under control.”

However, updated data presented by IPS in July showed a very different picture. In May alone, Ketziot recorded 2,500 cases. A broader chart revealed that while around 500 scabies cases were recorded across all Israeli prisons in March, that figure surged into the thousands starting in late April. The outbreak peaked in June, with nearly 3,000 prisoners diagnosed. As of July 6, that number had dropped to 1,400 — a figure that still matches a previous high set in November 2024.

“The data shows that what they told the court did not reflect what was actually happening on the ground. It shows how the state deals with this in court — by not stating the reality,” said Adi Lustigman, an attorney who contacted the IPS on behalf of Physicians for Human Rights–Israel.

In a statement issued to The Times of Israel, the Israel Prison Service responded: “The IPS operates in full cooperation with the Health Ministry to address the spread of scabies in the prison system, in accordance with professional protocols and binding medical guidelines. In cases where an infection is suspected, immediate measures are implemented, including isolation, medical treatment, severing contact with the general prison population, and additional steps to maintain personal hygiene and cleanliness.”

Even before the October 7 massacre and the ongoing war in Gaza, Israel’s National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir had pushed for harsher jail conditions for Palestinian security prisoners.

In February 2023, he ordered the closure of bakeries run by inmates in Nafha and Ketziot prisons, stating the move was intended to “prevent privileges for terrorists.” The decision ended up increasing prison costs, as the IPS was forced to buy bread from external suppliers.

Following the outbreak of war and the sharp rise in detainees for whom the IPS was responsible, Ben Gvir declared a “state of emergency in prisons” in early October 2023. The measure reduced living space per inmate, and the Knesset passed an emergency law that allowed authorities to worsen living conditions for prisoners, rolling back previous entitlements.

While the legislation made no distinction between criminal and security inmates, its practical implementation mostly affected the latter, especially in terms of reduced food rations and other targeted restrictions.

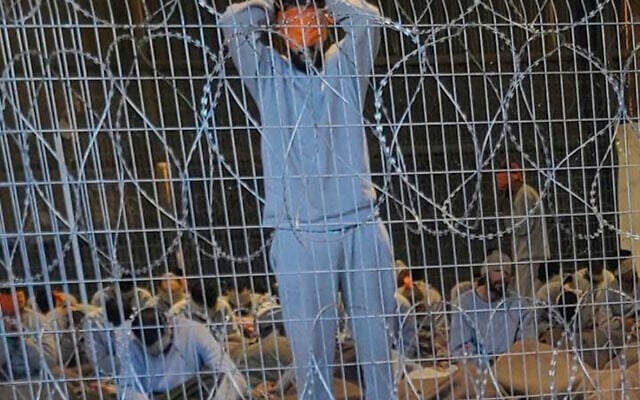

Before the war, the average number of security prisoners per cell was five or six. Today, testimonies indicate that some cells hold 14 to 16 people.

“The emergency law allows for certain things to be withheld — reduced time in the yard, fewer showers,” said Lustigman, who has tracked the treatment of security detainees. “The overcrowding also facilitates the spread of disease. What we’re seeing is a level that falls below previously accepted standards and below human dignity. If someone needs a doctor and doesn’t see one, if someone can’t go outside during the day, that’s a violation of basic human dignity.”

Since October 7, Ben Gvir has repeatedly called for harsher measures against security prisoners.

In December 2024, after the High Court of Justice issued a conditional order compelling the state to explain why it had reduced food rations to the point of significant weight loss among detainees, Ben Gvir issued a defiant response.

“Indeed, on my watch, the era of feasts, marmalades, and lamb meat is over,” he said. “There are no more bakeries and no more canteens funded with terror money. Terrorists’ prison cells will not be hotels again. The High Court wants to return us to the days of summer camps and all-inclusive resorts.”

July 2025 is the second consecutive month in which Israel has broken its record for the number of incarcerated security prisoners since HaMoked began tracking monthly figures in 2008.

According to IPS, the total prison population in Israel — both criminal and security inmates — stands at 24,000 as of July. This number does not include thousands of security detainees being held in military facilities under IDF control.

The surge in detainees stems from sweeping arrest campaigns carried out by the IDF across the West Bank since October 7, amid fears of another Hamas-style surprise attack. In addition, thousands of Palestinians have been arrested in Gaza during the prolonged war.

In response to the growing number of security detainees, Israel has significantly expanded its use of military detention facilities, holding not just dozens but hundreds and even at times thousands of Palestinians in sites operated by the IDF rather than the IPS.

In June, Israel confirmed that 2,790 Palestinian detainees from the Gaza Strip were held in Israeli jails and detention facilities. Of those, 660 are being held in military detention facilities. Since December, Israel has freed 1,244 Gazan detainees — mostly in the hostage-ceasefire deal with Hamas earlier this year.

The first of these IDF facilities was the Sde Teiman base in southern Israel, and in the months since the war began, the military has established additional sites.

Sde Teiman has been used by the army since 2009 to hold Palestinians from Gaza arrested during Israeli military operations. During the current war in Gaza, the number of detainees held there has increased dramatically.

On July 21, Qumber visited detainees at Sde Teiman, some of whom were also infected with scabies.

“They said they’re allowed to shower twice a week, for three minutes at most, and then the water is shut off,” she said. “They’re given a single piece of soap for 14 or 16 inmates sharing a cell. Some have scabies, some don’t, but they’re not separated. They’re not put in isolation until they recover. They’re all using the same bar of soap and two towels for everyone. They sleep on filthy mattresses for long periods. The main reason for infection is the lack of hygiene.”

Since 2024, international media have reported disturbing testimonies from Sde Teiman. In the first year of the war, detainees described being held in cages rather than proper buildings, sometimes shackled for hours or even days.

Following a petition filed with Israel’s High Court last year over the conditions at Sde Teiman, most of those detained in the early months of the war were transferred from IDF custody to IPS-run facilities.

Still, most Gazans arrested today are initially held at Sde Teiman for several weeks before being moved to other facilities — either IPS prisons or new detention sites set up by the military in response to the court petition, often near existing prisons.

Even in these alternative facilities, reports of mistreatment persist. In January 2025, the public broadcaster Kan published testimonies of severe physical abuse allegedly carried out by soldiers and officers in both Sde Teiman and other army-run sites — including a military detention facility hastily established near Ofer Prison during the war and a smaller military site in Anata (at the Anatot base), near Jerusalem. In June, Israel confirmed that a military detention facility at the Anatot base had been closed.

The IDF Spokesperson stated in response to a query from The Times of Israel: “The national responsibility for the incarceration of security detainees lies with the Israel Prison Service. Due to the shortage of prison space within the IPS, organizational and structural processes were carried out to support the IDF’s operational need for handling security-related arrests.

“Upon arrival at the facility, detainees are examined by a physician, and regular medical inspections are conducted at the site. The detainees receive appropriate medical care, in accordance with international law, and when necessary, they are transferred for treatment under the Health Ministry.

“Hygiene products are provided to the detainees as needed and as required by law. They are given regular access to showers and sanitary conditions in accordance with legal standards.”

The emergency regulation passed in October 2023 did not specifically address food provisions for security prisoners, but since the October 7 attack, there has been mounting evidence of a significant reduction in the quantity and quality of food provided to detainees.

In an ongoing High Court petition filed in April 2024, the Association for Civil Rights in Israel presented testimonies from security prisoners describing extreme and prolonged hunger and deteriorating food conditions in prison. Among the accounts was that of a diabetic inmate who said he had resorted to eating toothpaste to raise his blood sugar, and others who reported losing dozens of kilograms over recent months.

One prisoner who remained anonymous testified: “Since October 7, 2023, I haven’t felt full even once… For four months, I was in a constant state of hunger. I lost almost 22 kilograms [48.5 lb].”

Another anonymous detainee at Ofer Prison stated: “For breakfast, [the 11 inmates in our cell] were given one container of yogurt or white cheese for the entire cell, so each person got about a teaspoon. For lunch, we were given one bowl of chickpeas or beans or peas or lentils and one bowl of rice for the whole cell — barely enough for four portions. So each inmate received about three or four teaspoons of rice.”

Mohammed Abu Mokh, a security prisoner held at Ketziot, submitted an affidavit to the court in May in which he said: “I’ve lost weight because of starvation in the prison. I sometimes feel dizzy. I weighed 70 kilograms [154 lbs] before my arrest; now I weigh 57 kilograms [125 lbs].”

The petition remains under review by the High Court, and both sides are currently awaiting a ruling.

In July, Israeli media outlet Haaretz published (Hebrew link) the account of a 16-year-old Palestinian detainee, who requested anonymity, stating he was released only after a parole committee found that he had become so underweight that his life was in danger. According to the investigation, this occurred due to food restrictions at Megiddo Prison, where he had been held.

The IPS did not respond to a request for comment about the case.

Qumber, who has monitored the medical condition of security prisoners over the past several months, is unequivocal about what needs to be done.

“Why did these inmates contract scabies? Because of violations in their most basic living conditions — regular access to showers, soap, and shampoo.

“To address the problem, first and foremost, prisoners must receive proper medical care — regular access to prison clinics and ongoing medical follow-up,” she said. “And, just as important, basic hygiene: clean clothes, showers, fresh air, and food. They’re simply not getting enough food.”

“We believe the government has a legal obligation to guarantee minimum living conditions,” added Lustigman. “When diseases are spreading, there’s no legal basis that can justify this. It violates both the law and human dignity.”