Every year during Ramadan, 32-year-old Palestinian journalist Rahma Ali joins thousands of worshipers at the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem during the month-long Muslim holiday. But last year, a few months after the October 7, 2023, Hamas invasion and amid Israel’s subsequent war in Gaza, Ali was denied entry for the first time.

“They saw that I was from Shuafat and said no. That’s never happened before,” she recalls.

A resident of the Shuafat refugee camp on the outskirts of Jerusalem, Ali says that Ramadan last year was a somber affair: “It was very sad because of the war, especially seeing what was happening in Gaza; nobody was celebrating.”

On the eve of Ramadan this year, about a month into Israel’s fragile ceasefire with Hamas, Ali says that the holiday will be better.

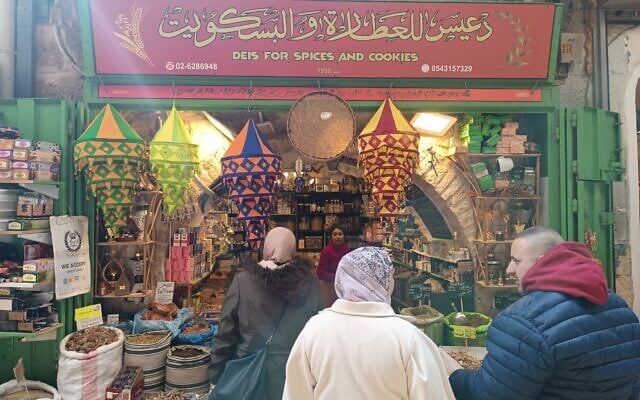

“Things are quieter now in Jerusalem since the ceasefire started,” she says. It’s not like it was even a few months ago. It feels like more businesses have reopened and just a lot more normal.”

In recent years, Ramadan has often served as a flashpoint for existing tensions between Israelis and Palestinians, sometimes leading to violent escalations, most notably in 2021 during the previous Israel-Hamas war, Operation Guardian of the Walls. With Ramadan likely to begin at sundown on Friday, there is great worry regarding the potential for violence.

Nivine, a Palestinian peace activist from the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Shuafat (not to be confused with the Shuafat camp), is very concerned about the rising tensions.

“Last year there were still feelings of hope, but not this year. The economic situation is so bad, the war in the West Bank is still going on, and we have fatigue from all of the deaths we’ve seen in Gaza. There’s anger mixed with a sense of helplessness,” says Nivine, who requested that her last name be withheld for her security.

With Israel’s ongoing operation in the West Bank, rising settler violence, the economic crisis, and lack of faith in domestic and international leadership for a long-term solution, there is ample tinder to ignite a wider escalation.

If that weren’t enough, US President Donald Trump is expected to soon announce his support for full or partial annexation of the West Bank — an event that Dr. Michael Milshtein, a senior analyst at Tel Aviv University’s Moshe Dayan Center and former head of the Department of Palestinian Affairs for the Israeli Military Intelligence (AMAN), warns will “add more fuel to the broader crisis.”

“I’m really afraid that we are reaching a point of implosion. If something dramatic takes place at the Temple Mount, it could trigger it,” Milshtein says.

Sensitivities regarding the Temple Mount, known as the Haram al-Sharif to Muslims, and specifically the Al-Aqsa Mosque, have historically served as a trigger for violence. Amid concerns over terror threats, Channel 12 reported that Israeli security services including the Shin Bet, Israel Police and the Defense Ministry have recommended limiting access to the Temple Mount during Ramadan to men over the age of 55, women over 50, and children under 12, and that a maximum of 10,000 people be admitted for Friday prayers. The government has yet to approve these measures.

In response, Hamas issued a Telegram statement urging Palestinian Muslims in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, as well as Arab Israelis, to flock to the Temple Mount and resist Israeli attempts to “desecrate and control” the site “by any means.”

The Israel Police said via their spokesperson’s unit that they are expecting thousands of worshipers and visitors to Jerusalem to visit the Old City, the Temple Mount and other holy sites. They would not comment on planned restrictions on worshipers or concerns about violence but said that “additional reinforcements” would be deployed across the Old City, the Temple Mount, surrounding neighborhoods and routes leading to worship sites, with “special attention… to areas connecting East and West Jerusalem and paths taken by worshippers.” Police deployments will be further bolstered on Fridays, particularly during the midday prayer.

Nivine says that the reportedly planned restrictions on worshipers and the added police presence at Al-Aqsa are akin to “pouring oil over a fire.”

“Every single time there is violence across the city, it usually goes back to the Al-Aqsa Mosque. You’re asking for trouble by limiting the numbers,” she says. “People are very angry, so any small trigger could have a larger effect.”

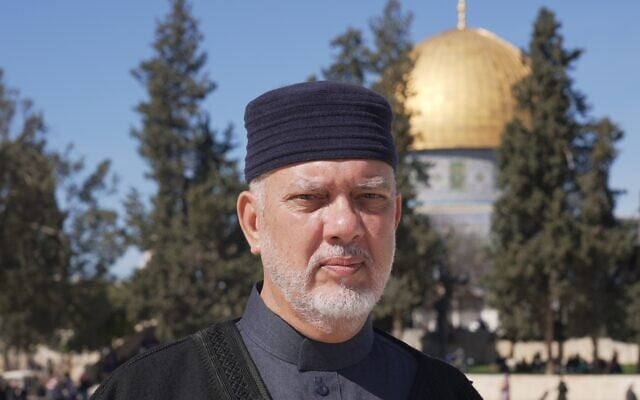

Prof. Mustafa Abu Sway, a member of the Islamic Waqf council that oversees the administration of Islamic holy sites including the Al-Aqsa Mosque, says that planned restrictions on worshipers constitute “a direct violation of the freedom of worship” as well as of the unwritten status quo agreement on the administration of shared religious sites.

The Jordanian-administered Waqf is responsible for managing Islamic holy sites in the city, most notably the Haram al-Sharif, where the Al-Aqsa Mosque sits. When Israel captured East Jerusalem during the 1967 Six-Day War, the government decided to maintain the Jordanian Waqf’s control over Muslim holy sites.

“The Waqf is responsible for administering inside of the [Al-Aqsa] mosque and Israel is responsible for outside of it,” says Abu Sway, who also serves as the Dean of the College of Islamic Studies at Al-Quds University and Chair for the Study of Imam Ghazali’s Work at the Al-Aqsa Mosque.

But Abu Sway claims that Israel has violated this agreement over the years, including by restricting the number of worshipers, especially — but not exclusively — during Ramadan.

“Youngsters are prevented from accessing Al-Aqsa regularly, even though there hasn’t been an incident [of violence] for 16 months,” says Abu Sway.

Despite the proposed restrictions, Abu Sway says that the Waqf’s preparations will continue as usual. These include providing medical teams for worshipers, prepping facilities, and study sessions that Abu Sway will help lead for the “thousands” of worshipers he expects to make their way to Al-Aqsa over Ramadan.

Ramadan is a stark reminder of the vast gulf in perceptions between Israelis and Palestinians. For Palestinian Muslims, it is an extremely sacred month. “All we want is to be left to pray and fast,” says Nivine. For many Israelis, however, Ramadan is often synonymous with violence and heightened security threats. For both peoples, it has become a time of extreme tension and fear, exacerbated by war and unrest.

“Ramadan is always a sensitive period of time,” says Brig. General (Res.) Yossi Kuperwasser, head of the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security, and former director-general of the Strategic Affairs Ministry.

“Especially now, with the ceasefire, which many Palestinians see as a Hamas victory due to the release of so many prisoners, we have to be prepared for an escalation,” Kuperwasser says.

Milshtein echoes this concern: “This will be one of the tensest Ramadans in years. I’m extremely concerned about the situation in Jerusalem and the West Bank.”

But for Abu Sway, it is the added police presence and potential restrictions on worshipers that are the impetus for, rather than a safeguard against, violence.

“I don’t accept the narrative that Al-Aqsa is inherently a hostile place or that Ramadan is a period of violence,” he says. “We used to host 400,000-500,000 people on Fridays during Ramadan and there were practically no restrictions or a single incident.”

For Palestinians, Jerusalem itself is central to fueling wider conflict. “Jerusalem triggers conflict in the West Bank,” says Nivine, “not the other way around.”

But for Israeli security analysts, violence in the West Bank is just as likely to trigger violence in Jerusalem, especially this year amid Israel’s ongoing offensive in the West Bank, known as Operation Iron Wall.

The operation was launched amid a wave of Palestinian terror attacks inside Israel and the West Bank in which 48 people have been killed. Another eight members of security forces have been killed in clashes with terror operatives in the West Bank.

Launched on January 21, the operation has included the recent deployment of tanks to the area for the first time in over 20 years. The army says it has killed more than 60 Palestinian terror operatives and arrested over 210 suspects. Meanwhile, Defense Minister Israel Katz said that 40,000 Palestinians had been “evacuated” from West Bank refugee camps since the start of the operation. The military has also admitted to unintended civilian casualties during the operation, at least two of which are under investigation.

Since October 7, 2023, Israeli forces have arrested around 6,000 Palestinians in the West Bank, including more than 2,350 linked to Hamas. The Palestinian Authority Health Ministry reports that over 900 Palestinians in the West Bank have been killed during this period. The military says that the vast majority of these casualties were combatants killed in firefights, rioters clashing with troops, or terrorists carrying out attacks.

Kuperwasser notes that while the operation has seen a high number of arrests made and weapons confiscated, it hasn’t succeeded in halting terror attacks coming from the West Bank.

“The attack on the buses took place just last week, so in that sense [the operation] hasn’t been effective,” he says, referencing the blowing up of three buses in Bat Yam and Holon and the attempted bombings of at least one more. Nobody was injured. “The attack was carried out by terrorists from Tulkarem, where the army has been very active.”

Beyond these heightened security concerns, both Palestinians and Israelis are quick to point out that the Palestinian economic crisis is just as significant in triggering unrest. Unemployment in the West Bank has soared from 12 percent before the war to over 30%, with around 300,000 people losing jobs — more than half of whom worked in Israel. Today, approximately 20,000-25,000 Palestinians work in Israel, mostly in the settlements, according to Milshtein.

“It is a long-held belief among the security establishment that higher employment, including through granting more permits to Palestinians to work in Israel, lowers the potential for violence,” says Milshtein, adding that security officials have urged Israel to grant more permits ahead of Ramadan. “But right now the government is in no mood to make gestures towards the Palestinians.”

Nivine says that much of this discourse reflects the widespread absence, and great need, for introspection.

“Sometimes it’s good to hold up a mirror to ourselves and think about what we are doing to trigger the other side,” she says.

However, this is a challenge due to the massive alienation felt between Palestinians and Israelis in the wake of October 7.

“Before, I felt like things were moving in a positive direction in Jerusalem, that we were normalizing having a shared city. People understood that with a lack of political horizons, we needed to find a way to share,” Nivine says. “That’s all been broken in the last 16 months.”