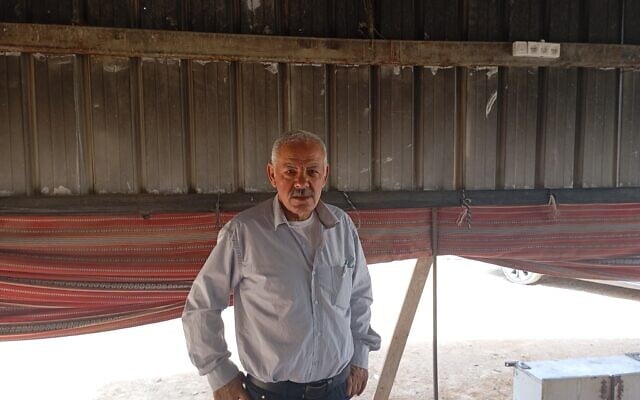

For Youssef Ziadna, marking the second anniversary of the October 7, 2023, massacre means reopening wounds he has struggled to live with since that dark day.

The 47-year-old minibus driver from Rahat still hears the screams from the Nova music festival near Kibbutz Re’im, where he drove straight into Hamas gunfire and pulled dozens of young Israelis to safety.

“I stared death in the face,” Ziadna told The Times of Israel this week, “but I couldn’t leave people behind.”

In the days after the attack, stories such as Ziadna’s spread across Israel — Bedouin men rescuing partygoers, soldiers and families from border communities — briefly uniting a nation in grief and pride. On Sunday night, Israel received from Hamas the body of another Bedouin October 7 hero, tracker Muhammad el-Atrash, who was killed fighting terrorists and whose remains were abducted to Gaza.

For his actions, Ziadna became a national symbol of courage — one of the first recipients of President Isaac Herzog’s newly created Medal for Civilian Bravery — as one of several Bedouin citizens who risked or lost their lives that day. Among the approximately 1,200 people slaughtered in southern Israel that day, 21 were Bedouin citizens. Six Bedouin were among the 251 abducted into Gaza.

Members of Ziadna’s own extended family were among those directly affected by the carnage: Abed, a relative, was murdered alongside his girlfriend Yulia Chaban at Zikim Beach, and four others were abducted — two of whom were later confirmed killed in captivity.

But as the war ground on, the sentiment of national unity faded. Today, Ziadna says that he struggles with depression, is unable to return to work due to physical ailments, and feels forgotten by the same country that hailed him as a hero.

Despite receiving threats from Hamas sympathizers, Ziadna says his request for a gun license was denied. Parents of Nova survivors — with whom he remains in warm contact — had urged him to apply for one, given that he continues to drive within the Gaza border region.

“They praised me on TV,” he said quietly, “but when I asked for help, the door was closed.”

Across the Negev, where thousands of Bedouin live in uneasy harmony with the state, many share Ziadna’s disappointment: despite their heroism and shared sacrifice on October 7, the hopes and promises for greater equality that followed have quickly faded.

A week after the October 7 attack, as funerals were still being held for Jewish Israelis and Bedouins alike, Atiya Abu Asa says he found a demolition order taped to his family home in an unrecognized village near Ar’ara BaNegev.

Residents of the village and others like it nearby had quickly mobilized in the face of the Hamas invasion. Some drove to Ofakim to assist first-responders under fire; others walked to the local police station, asking how they could help.

“People even went to Ashkelon and to the district headquarters,” recalled Abu Asa, one of the village leaders. “We didn’t wait for anyone to call us — we just went to help. And then the state came for our houses.”

In recent months, residents say, demolition orders have arrived even at the homes of Bedouin reservists serving in the military or recently returned from the front. Today, around 1,500 Bedouins serve in the IDF, according to Defense Ministry data, and several Bedouin soldiers have also been killed fighting in Gaza.

According to Ilan Amit, co-director of an Arab–Jewish civil-society organization in Beersheba, enforcement of illegal structures has reached levels unseen in decades.

“I’ve been working in the Negev for more than 20 years,” he said. “I’ve never seen anything like this — entire villages being bulldozed. It’s the worst situation for Bedouins since the establishment of the state.”

For decades, Israel has been trying to convince scattered, off-the-grid Bedouin villagers that it is in their interest to move into government-designated Bedouin townships, where the government can provide them with water, electricity and schools.

The High Court has previously deemed many of the unrecognized Bedouin villages illegal, and the government has said they are trying to bring order to a lawless area and give a better quality of life to the impoverished minority.

The Bedouin allege that Israel is seeking to clear the land to develop new towns for Jewish settlement. They assert that they have roamed the area since long before Israel was founded, were driven out during the War of Independence in 1948, and were resettled there in the 1950s by the martial law administration imposed on many largely Arab-populated areas during the state’s early years.

The demolitions, Amit said, are part of a wider crisis in the Negev, home to some 280,000 Bedouin citizens, about 100,000 of whom live in roughly 40 unrecognized villages without infrastructure, planning rights, or bomb shelters.

In Rahat — Israel’s largest Bedouin city and among its poorest — residents are also grappling with a surge in violent crime, including a recent shooting that left an 8-year-old boy dead.

In November 2024, far-right National Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir bragged that under his watch, demolitions of illegal homes in the Negev had increased by 400 percent. Community activists confirm that there has been a sharp uptick in home demolitions under the current government, though the actual number may be more modest than Ben Gvir’s claim.

Earlier this year, a report came out claiming that Ben Gvir told police to prioritize demolishing illegally constructed buildings used as family homes, overstepping the bounds of his authority in an apparent attempt to target Israel’s Arab community.

Naomi Kahn, director of the international division at Regavim — an NGO founded by Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, an ally of Ben Gvir, that monitors land use and advocates for enforcement of planning laws — said many of the structures are “illegal encampments on Israeli state land” that block lawful development.

“In the end, no one should be building illegally anywhere under the jurisdiction of the State of Israel,” said Kahn. “Reservists who serve the country should get consideration — but the law still has to be enforced.”

The Israel Land Authority denied that Bedouin were being targeted. Enforcement operations “are carried out in accordance with the law and court rulings against trespassers and illegal squatters in all sectors and across the country, to ensure that state lands remain available and properly and equally managed,” a spokesperson told The Times of Israel.

The authority added that “in cases involving soldiers and reservists serving on the front lines, the ILA reviews relevant cases with sensitivity and discretion in determining the timing of enforcement,” noting that it “encourages and supports reserve service through special benefits, including specific benefits for Bedouin soldiers and members of the security forces.”

In August 2024, the ILA said it had decided not to serve a demolition order for the home of Farhan al-Qadi, a Bedouin man held hostage for 10 months before being rescued from a tunnel by troops. But it would not comment on the fate of the homes of his neighbors in the unrecognized Bedouin village of Khirbet Karkur, where over two-thirds of structures were slated to be razed.

In Rahat, Hanan al-Sana, co-CEO of Itach Ma’aki – Women Lawyers for Social Justice, has spent the last two years trying to transform the pain of October 7 into renewed partnership. In the chaotic days after the attack, she helped found the Jewish-Arab Emergency Task Force, turning her pre-war women’s rights network into a lifeline for communities suddenly cut off by the fighting.

“When Jewish and Arab women pack food together in a dusty village, they’re not just packing meals — they’re packing hope,” said al-Sana. “We’re in a crisis, yes, but crisis also means opportunity.”

In the months that followed, the Task Force helped launch small joint projects — from food drives for single-parent families to dialogue groups for women across the south.

“If we can work together in war,” al-Sana said, “we can rebuild trust in peace.”

Ziadna still clings to that fragile trust. After stopping therapy for several months, he said he has now started meeting again with his psychologist, trying to quiet the painful memories that return each night.

“We will keep living,” he said softly. “Jews, Arabs, Druze, Christians — we are all citizens of the State of Israel. First of all, be a human being. That’s the most important thing.”

Times of Israel staff contributed to this report.