On June 15, just two days after Israel launched its attack on Iran’s nuclear program, police arrested two young men in Tiberias based on a tip from the Shin Bet security agency.

Yoni Segal, 18, and Omri Mizrahi, 20, allegedly planned to fly abroad, possibly to Cyprus, en route to undergo weapons training in Iran. Their mission, according to a state prosecutor’s indictment: to assassinate a top Israeli scientist in exchange for NIS 200,000 ($60,000) each.

In an indictment filed in early July, prosecutors alleged that the defendants’ handlers promised to grant them and their families safe haven in Iran, “where all their needs would be met and the defendants would comfortably live out the rest of their lives.”

The plot marked one of Iran’s most dramatic recruitment attempts uncovered in Israel in recent months — but by no means the only one.

Since the outbreak of the war with Hamas in Gaza, Israeli authorities say they have ferreted out dozens of their own citizens allegedly recruited by Iran for espionage and other activities, from plotting assassinations to spray-painting pro-Iran slogans on cars.

The growing number of alleged Iranian agents has even prompted Israel to open up a new wing for them in Haifa’s Damon prison.

As of July, law enforcement had arrested at least 45 suspects involved in 25 separate cases since October 7, 2023, an Israel Police spokesman told The Times of Israel. Charges have been filed against 40 of them, according to a security official.

The only conviction so far has been of an Israeli businessman who was likely targeted rather than recruited randomly, as many of the others appear to have been.

The unlikely operatives, from diverse walks of life, are usually ordinary civilians contacted by Iranian intelligence officers online. The effort appears to be part of a mass recruitment scheme by Tehran to gather intelligence on Israel’s alleged nuclear and military sites, as well as key Israeli figures such as defense officials and top scientists.

“Iran tries to recruit as many [spies] as possible. Maybe most of them are small fish, but they’re hoping eventually to catch a big shark, recruit a quality agent — that’s their way,” explained reporter and spycraft expert Yossi Melman in an interview with The Times of Israel.

The suspects in Israel, state prosecutors’ indictments show, come from all corners of the country’s society. Among those charged with espionage are Russian-Israeli soldiers from the Haifa suburbs, a Haredi man from Bnei Brak, a West Bank settler and an Arab Israeli college student.

The common thread linking these suspects is not ideology but the promise of quick cash. Spies usually begin by carrying out seemingly innocuous tasks for small sums of money, which quickly escalate into severe offenses such as intelligence gathering and even assassination plots, the indictments show.

The Shin Bet has not responded to requests for comment.

For Iran, the recruitment effort may be its way of trying to even the score after years of successful espionage and sabotage activities attributed to Israel, including assassinations of nuclear scientists and damaging attacks on nuclear sites.

During the opening of the 12-day Israel-Iran conflict, Israel deployed an extensive spy network it had cultivated in Iran, with attacks on scientists and secret meetings of military officials giving a window into the depth and breadth of its intelligence on Tehran’s inner sanctums.

In the weeks since, Iran has arrested some 700 alleged spies and collaborators working with Israel’s Mossad spy agency, according to Iran’s semi-official Fars news outlet. On Monday, the head of the country’s judiciary called for the cases to be expedited, the official Mizan news outlet reported.

Despite the effort, Tehran hasn’t yet succeeded in taking out any of the Israeli targets in its crosshairs, though there have been several close calls. There are also suspicions that intelligence gathered by spies could have helped Iran target key sites during the war in June, in which the Islamic Republic fired hundreds of ballistic missiles at Israel.

Among other targets, Iranian missiles hit the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Soroka Medical Center in Beersheba and, an Israeli official told Reuters, a number of military sites. The barrages were in response to Israel’s sweeping assault on Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missiles programs. Israel said the attack was necessary to eliminate the “existential threat” posed by the Islamic Republic, which openly calls for the destruction of the Jewish state.

Iranian state media claimed in early June that Iran had obtained a vast trove of “strategic and sensitive” Israeli intelligence, including files related to Israel’s nuclear facilities and defense plans, but no evidence was provided to support the claims.

Iranian espionage in Israel is not a new phenomenon. But in the past, Melman said, it was usually targeted toward recruiting Arab citizens of Israel seen as more likely to be sympathetic to the cause, and complemented by efforts by Palestinians and the Hezbollah terror group in Lebanon.

“It was very few and far between, continuous throughout the years but minimal,” he noted.

Over the past two and a half years, though, Iran has been trying to build up an espionage network within Israel through what Melman called a “spray-and-pray” approach — agents casting a wide net across all parts of society in hopes of stumbling upon a few quality recruits.

This involves Iranians reaching out to Israelis through social media — most recent cases have been through the Telegram messaging app, which has relatively lax content moderation rules — with offers of money in exchange for carrying out missions of escalating severity.

According to police, recruits have vandalized bus stops, photographed and filmed the Iron Dome air defense system batteries and army bases, stalked public figures and, in extreme cases, even set in motion assassination plots. They normally receive payments in the form of cryptocurrency.

The accused spies are a diverse crowd, varying drastically in age, ethnicity and religious observance. While the suspects are all seemingly lured by the promise of easy money, Iranian recruiters also appear to be trying to take advantage of rising disaffection with Israel’s leadership among wide swaths of the public.

Many recent espionage incidents uncovered by the Shin Bet have involved young Israelis, often university students or recently released IDF soldiers.

“There’s no ideology here, it’s only the money,” said Melman. But it’s also evident that Iranian agents pay careful attention to Israel’s political contours and appear to exploit surging polarization to reel in potential recruits.

At least one Iranian handler has specifically sought out Haredi and Muslim recruits, according to an indictment filed against 22-year-old Bashar Musa, a Ben-Gurion University student arrested in June.

According to prosecutors, Musa was instructed to invite his Iranian handler to additional Telegram groups specifically geared toward the ultra-Orthodox and Muslim communities.

His lawyer did not responded to a request for comment.

In many cases, including the recent assassination plot, agents reached out to Israelis under a political pretense, describing themselves as acting “on behalf of Kaplanist leftists” — a reference to anti-government protesters who regularly demonstrate in Tel Aviv — and similar phrases.

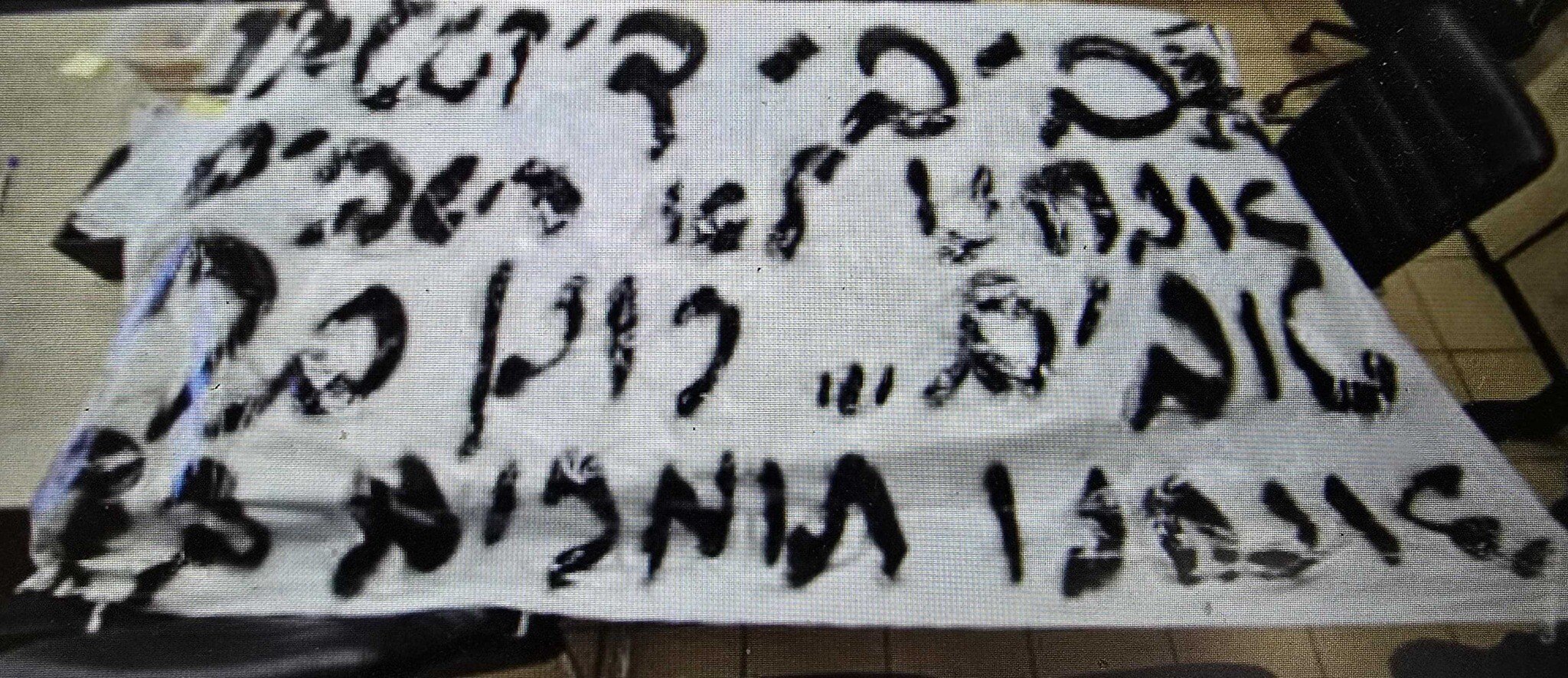

The two would-be assassins from Tiberias had allegedly started out with minute tasks — scrawling “Bibi is a dictator” on slips of paper and banknotes, then filming videos of themselves burning the messages.

To Melman, the spy cases show the degree to which Iranians have been able to exploit a deep malaise plaguing Israeli society. He painted a picture of a fragmented, war-weary Israel, in which citizens are quickly losing trust in elected officials amid rampant polarization, and appear increasingly motivated by their personal finances.

“Israelis were never ready to spy, except for a small fraction of them. If they did, it was typically ideological missions for the USSR,” he said. “But to spy for an enemy country? This is the deterioration of society, there’s no other word for it.”

According to Melman, in some cases Iranian agents reaching out to potential recruits are not bothering to conceal their identity.

Iranians have used this tactic more and more in recent months, Melman said, on the assumption that an increasing number of Israelis “are willing and ready” to defect to the Islamic Republic.

Fadi Hamdan, a lawyer for Segal, argued that his client had no clue he was in contact with an Iranian agent. He later dropped the case and it was taken up by Avi Moskowitz, a lawyer in the Public Defender’s Office. He told Ynet that his client is a “young, Zionist, normative individual who had no intention of harming national security.”

But the indictment indicates that Segal indeed knew he was chatting with an Iranian agent. The charges detail that he saw that his handler was located in Tehran after the two exchanged locations over an encrypted messaging app.

Yuval Zolti, the lawyer for Mizrahi, said he could only give a statement on his client’s innocence once provided the legal documents detailing the alleged offenses.

Even when handlers aren’t completely upfront about their motives, many accused spies seem to have understood that an Iranian agent was sitting behind the keyboard. Such was the case with 33-year-old Mark Morgain, a West Bank settler arrested in late June.

According to an indictment, Morgain had been contacted earlier that month by an Iranian agent under the alias “Alex” who offered to pay him a daily retainer to do his bidding, including transporting an explosive and filming a missile interception.

Prosecutors say Morgain suspected his handler was Iranian, but told Alex that he “doesn’t want to know” whether he was working on behalf of the enemy country, calling the prospect “irrelevant.”

The Times of Israel was unable to reach Morgain’s lawyer for comment.

Some suspects, however, indeed seem to have fallen prey to subterfuge, as in the case of a 13-year-old boy from Tel Aviv who was arrested on suspicion of vandalizing bus stops at the behest of an Iranian agent.

The suspect, who has since been released to house arrest, had also been asked to take photos of the Iron Dome missile defense system, but refused, authorities said.

His lawyer told The Times of Israel that the boy blocked the contact before his arrest. He predicted that an indictment was unlikely, due to both the suspect’s age and his lack of awareness.

In the early 2010s, Iranian agents managed to turn former government minister Gonen Segev into one of its spies, running him for some six years until he was caught and sentenced to 11 years in prison.

In April, an Israeli businessman with ties to Turkish and Iranian figures was sentenced to 10 years in a plot that saw him smuggled twice into Iran, where he negotiated prices for hiring hitmen to assassinate senior officials, according to prosecutors.

With such assets hard to come by, though, Iranian intelligence operatives are also casting a wide recruitment net in the hopes that they will chance upon “a quality agent” with access to the upper echelons of Israeli society, Melman said. They do not appear to have yet succeeded.

To vet the potential agents, handlers often demand their new recruits send “verification videos” displaying their faces and identity cards, then task them with minor criminal violations in exchange for money.

These smaller tasks ensure the recruits’ commitment, and “chains them” early on to their operator, said Melman. “You’re in their hands now, you’ve already committed one crime.”

In many cases, according to court papers and reports, recruits have been willing to do these smaller tasks like vandalism or taking picture, but balk when asked to take more serious actions, like tracking targets or killing high-ranking officials.

The closest the Iranian operation has come to murder so far appears to have been an assassination attempt on a Israeli physicist who formerly held a prominent position in the Weizmann Institute of Science. A group of young men from Jerusalem’s Arab neighborhood of Beit Safafa were recruited to kill him.

The men were intercepted by security services at the research center’s entrance on the night of September 15, and soon gave up on their plan. They were later arrested and charged.

So agents turned to another recruit, 24-year-old Bnei Brak resident Asher Binyamin Weiss, asking him to assassinate the scientist and his family, and then to torch his house, according to court papers and media reports. Weiss took photos of the physicist’s home and car, but in the end declined to harm his target.

Iran did, however, succeed in targeting the esteemed research center during its war with Israel, seemingly using the same level of precision it employs in its spy campaign.

On June 15, the Islamic Republic fired a volley of ballistic missiles at the Rehovot university. One missile managed to find its target, destroying two empty buildings, damaging dozens more, and wrecking some 45 labs. But others rained on residential parts of the city at random, destroying apartments and wounding dozens of uninvolved civilians, including a Filipina caregiver who died of her wounds on Sunday.