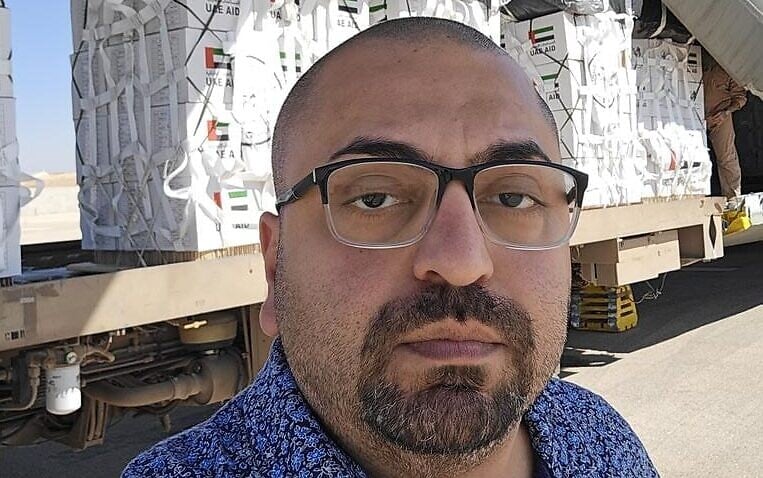

For activist Ahmed Fouad Alkhatib, flying over the Gaza Strip on a humanitarian mission this week to drop pallets of aid into the beleaguered enclave marked something of a bookend.

Twenty-five years ago, Alkhatib arrived in his family’s native Gaza from Saudi Arabia on a flight that landed at the Strip’s airport — a short-lived symbol of the era’s heady aspirations for Palestinian peace and prosperity.

On Monday, two decades after he left the Strip, he was back on a plane over Gaza, getting a 10,000-foot view of how those hopes had shriveled into misery and destruction.

“Flew into Gaza’s airspace for the first time in 25 years, after my Palestinian Airlines 2000 flight into the Strip’s int’l airport,” Alkhatib wrote on X following the flight.

Alkhatib was last in the Strip in 2005, when he was 15 years old. He left the enclave for what was meant to be a temporary stint in the US on an exchange program.

But by the time he was set to come back, his return was stymied by a blockade placed on Gaza following the kidnapping of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit.

Separated from his family, who remained in Gaza, Alkhatib eventually applied for political asylum in the United States with the help of aid organizations and peace activists. Today, his older brother is still in the enclave, while the rest of his family have either left the Strip or been killed.

An outspoken critic of Hamas, Alkhatib today heads Realign For Palestine, an Atlantic Council project aimed at building support for Palestinian statehood and challenging entrenched narratives in the conflicts.

“After Oct 7, I decided to invest in having a presence on social media to humanize the Palestinians in Gaza, share sorely lacking voices and perspectives, and specifically engage with audiences outside of my own side/echo chamber,” Alkhatib wrote in a Times of Israel blog in January 2024. “Dialogue and engagement between Palestinians and Jews/Israelis are desperately needed first steps to establish human-to-human connections and inject grassroots fuel for a different future.”

He is also critical of Israel, holding the country responsible for the deaths of over two dozen relatives during the war. However, he has been steadfast in tempering his rhetoric in the name of fostering dialogue and what he calls “radical pragmatism.”

Those ideas, he says, have been embodied by the United Arab Emirates, which agreed in 2020 to normalize ties with Israel, becoming the first country to join the Abraham Accords.

“I have generally been an admirer of the UAE model and think it can be helpful to Gaza — in terms of economic prosperity, in terms of radical pragmatism, as well as their relationship with Israel,” he told The Times of Israel in a video interview from the UAE. “There has been leverage, very pragmatic, to now become one of the most significant, top providers of aid to the Gaza Strip — something like 42 -48% of the overall aid to Gaza is provided by the UAE.”

Alkhatib said he reached out to Abu Dhabi to see if he could have a look at what went into the country’s humanitarian efforts in Gaza.

The UAE agreed, he said, and offered him the opportunity to participate in the airdrops and to better understand the full logistical effort involved.

The UAE is one of several countries to have joined an effort to drop aid into the Strip, where humanitarian officials allege that people are starving amid Israeli restrictions on land-based deliveries of assistance. Israel began authorizing the airdrop operations in late July.

On X, Alkhatib documented his journey from Abu Dhabi, where the donated supplies were collected, to Amman, Jordan — where the pallets of aid were attached to parachutes and loaded onto military planes — and finally over Gaza, where the packages, each weighing hundreds of kilograms, are pushed out of bay doors toward the hungry people below.

The Jordanian army is responsible for inspecting the aid packages that arrive at a military base near Amman and for the logistical process of organizing the packages and attaching them to parachutes. The Jordanian army also takes part in most of the airdrops, using Jordanian aircraft alongside planes from the countries that donated the aid.

Alkhatib first joined an air mission on Monday, and overflew the Strip again on Tuesday.

“It’s a two-and-a-half-hour flight from Abu Dhabi to Amman. This is a massive aircraft I rode along on. Right now we are trying to unload the food from the plane, get it palletized in the warehouses… and then it will be airdropped into Gaza,” Alkhatib said in a video on August 25.

Hours later, he shared another video showing the successful transfer of the Abu Dhabi donations — food and medical supplies — to the aircraft that would drop them over Gaza.

“We’re about to start loading the C-130 right now — it belongs to the UAE — with the food pallets that are on these lightweight pallets here, with the parachute on top. The C-130 is smaller than the one we flew in with yesterday. The goal is to deploy more targeted airdrops in areas of northern Gaza that are most difficult to access,” he said.

During his flight on Tuesday, Alkhatib filmed the devastation in Gaza as he flew the length of the Strip, emotionally documenting widespread devastation and noting where his family had lived.

“It looked like a desolate desert in parts, where all the greenery and farmland were gone,” he told The Times of Israel. “And then it looked like something out of World War II. You can’t even imagine it. Just seeing it up close… there’s nothing I can say to describe what it looked like.”

Israel allowed international airdrop missions in the early months of the war, but the effort was discontinued in March 2024 without official explanation.

Humanitarian groups have noted that only small amounts of aid can be delivered by plane, and that the method can be dangerous, exposing Gazans to being hit by falling pallets weighing up to a ton.

According to Israel’s Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories, since the resumption of airdrops, 541 tons of food have been delivered into Gaza from the air. By comparison, over the past month, 115,000 tons of aid entered by land, Israel says.

But both Israeli and UN officials say most aid sent in by truck is intercepted before it can reach its destination, either by Gazan civilians desperate for food or organized looters.

“Airdrops are effective in certain regards but certainly inefficient,” Alkhatib said. “The drops are random, they don’t happen in the same place twice, and they’re easy for people to quickly intercept before Hamas or criminal groups can steal them. They’re part of the broader strategy of flooding Gaza with food.”

However, officials from countries participating in the airdrops told Alkhatib dropping food from planes can be preferable because it bypasses the lengthy bureaucracy needed to get food through via border crossings.

Aside from the UAE, participating countries include Jordan, Belgium, France, Singapore, the Netherlands, Italy, and even Indonesia — a Muslim country with no diplomatic ties to Israel that was nevertheless authorized to deliver aid.

Alkhatib, who met with Indonesian representatives, said Jakarta had joined the airdrop effort due to difficulties it had in sending aid by land.

But humanitarian groups say that in recent weeks, Israel has eased restrictions on collecting aid from the border crossings, after months of disputes over delays in pickups.

“Israel does not restrict or prevent UN trucks from entering, nor does it impose quantitative limits on humanitarian aid to the Strip,” COGAT said in an August 22 statement.

The opportunity to fly over Gaza was especially poignant for Alkhatib, who in 2015 founded a nonprofit aimed at advocating for a humanitarian airport in the Strip to ferry goods into enclave, describing himself as having a lifelong passion for aviation fostered by his first flight into Gaza.

The civilian airport that he flew into in 2000, in the southern city in Rafah, was bombed by Israel in 2002 during the Second Intifada, and was gradually abandoned in subsequent years. By 2022, its former runway had been turned into agricultural fields, though the shells of its terminal and control tower still stood. Today, satellite photos show, all that remains of Gaza’s onetime airport is rubble.