Sayeh Seydal, a jailed Iranian dissident, narrowly escaped death when Israeli missiles struck Tehran’s Evin Prison, where she was imprisoned. She had just stepped out of the prison’s clinic, moments before it was destroyed in the blasts.

The June 23 strikes on Iran’s most notorious prison for political dissidents killed at least 71 people, including staff, soldiers, visiting family members, and people living nearby, Iranian judiciary spokesman Asghar Jahangir claimed Sunday. In the ensuing chaos, authorities transferred Seydal and others to prisons outside of Tehran — overcrowded facilities, known for their harsh conditions.

When she was able to call her family several days ago, Seydal pleaded for help.

“It’s literally a slow death,” she said of the conditions, according to a recording of the call provided by her relatives, in accordance with Seydal’s wishes.

“The bombing by the US and Israel didn’t kill us. Then the Islamic Republic brought us to a place that will practically kill us,” she said.

Iran’s pro-democracy and rights activists fear they will pay the price for Israel’s 12-day air campaign aiming to cripple the country’s nuclear program. Many now say the state, reeling from the breach in its security, has already intensified its crackdown on opponents.

Israel’s strike on Evin — targeting, it said, “repressive authorities” — spread panic among families of the political prisoners, who were left scrambling to determine their loved ones’ fates. A week later, families of those who were in solitary confinement or under interrogation still haven’t heard from them.

Nobel Peace Prize laureate Narges Mohammadi, a veteran activist who has been imprisoned multiple times in Evin, said that Iranian society, “to get to democracy, needs powerful tools to reinforce civil society and the women’s movement.”

“Unfortunately, war weakens these tools,” she said in a video message to The Associated Press from Tehran.

Many now fear a potential wave of executions targeting activists and political prisoners. They see a terrifying precedent: After Iran’s war with Iraq ended in 1988, authorities executed at least 5,000 political prisoners after perfunctory trials, then buried them in mass graves that have never been accessed.

Already during Israel’s campaign, Iran executed six prisoners who were sentenced to death before the war.

The Washington-based Human Rights Activists in Iran documented nearly 1,300 people arrested, most on charges of espionage, including 300 for sharing content on social media, in just 12 days.

Parliament is fast-tracking a bill allowing greater use of the death penalty for charges of collaboration with foreign adversaries. The judiciary chief called for expedited proceedings against those who “disrupt the peace” or “collaborate” with Israel.

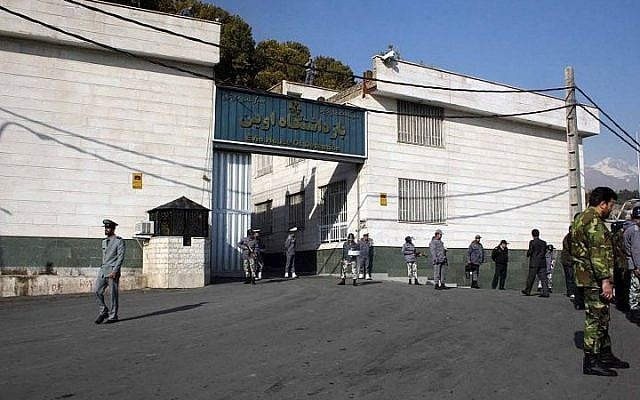

Evin Prison, located in an upscale neighborhood on Tehran’s northern edge, housed an estimated 120 men and women in its general wards, as well as hundreds of others believed to be in its secretive security units under interrogation or in solitary confinement, according to HRA.

The prisoners include protesters, lawyers, and activists who have campaigned for years against Iran’s authoritarian rule, corruption, and religious laws, including the enforcement of Islamic attire on women. Authorities have crushed repeated waves of nationwide protests since 2009 in crackdowns that have killed hundreds and jailed thousands.

The strikes hit Evin during visiting hours, causing shock and panic.

Seydal, an international law scholar who joined protest movements over the past two decades and has been in and out of jail since 2023, recounted to her family her near brush with death in the prison clinic. The blast knocked her to the ground, a relative who spoke to Seydal said, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals.

Visiting halls, the prosecutor’s office, and several prisoner wards were also heavily damaged, according to rights groups and relatives of prisoners. One missile hit the prison entrance, where prisoners often sit waiting to be taken to hospitals or court.

At the time, Defense Minister Israel Katz said only that a missile was fired at the prison gates amid a wave of strikes on “regime targets and governmental repression bodies.�

IDF Spokesman Brig. Gen. Effie Defrin said the same day that the strike was carried out “in a pinpoint manner, to avoid harm to those uninvolved.”

“Attacking a prison, when the inmates are standing behind closed doors and they are unable to do the slightest thing to save themselves, can never be a legitimate target,” Mohammadi said. Mohammadi was just released in December when her latest sentence was briefly suspended for medical reasons.

During the night, buses began transferring prisoners to other facilities, according to Mohammadi and families of prisoners. At least 65 women were sent to Qarchak Prison, according to Mohammadi, who is in touch with them. Men were sent to the Grand Tehran Penitentiary, housing criminals and high-security prisoners. Both are located south of Tehran.

Mohammadi told AP that her immediate fear was a lack of medical facilities and poor hygiene. Among the women are several with conditions needing treatment, including 73-year-old civil rights activist Raheleh Rahemi, who has a brain tumor.

In her call home, Seydal called Qarchak a “hellhole.” She said the women were packed together in isolation, with no hygiene care, and limited food or drinkable water.

“It stinks. Just pure filth,” she said.

“She sounded confused, scared and very sad,” her relative said. “She knows speaking out is very dangerous for her. But also being silent can be dangerous for her.” On Sunday, Sayeh made another call to her family, saying she was briefly taken back to Evin to bring her belongings. The stench of “death” filled the air, her relative quoted her as saying.

The 47-year-old Seydal was first sentenced in 2023. In early 2025, her furlough was canceled, and she was assaulted by security and faced new charges after she refused to wear a chador at the prosecutor’s office.

Israel began an air campaign against Iran’s nuclear and military infrastructure on June 13, saying its sweeping assault on Iran’s top military leaders, nuclear scientists, uranium enrichment sites, and ballistic missile program was necessary to prevent the Islamic Republic from realizing its declared plan to destroy the Jewish state.

Iran responded to the Israeli attacks with near-daily barrages of missiles at cities, killing 28 people and wounding thousands, according to health officials and hospitals.

After the US also bombed key Iranian nuclear sites last week, Washington brokered a ceasefire between Israel and Iran.

Mehraveh Khandan grew up in a family of political activists. She spent much of her childhood and teen years going to Evin to visit her mother, rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, who was imprisoned there multiple times.

Her father, Reza Khandan, was thrown into Evin in December for distributing buttons opposing the mandatory headscarf for women.

Now living in Amsterdam, the 25-year-old Mehraveh Khandan frantically tried to find information about her father after the strike. The internet was cut off, and her mother had evacuated from Tehran. “I was just thinking who might die there,” she said. It took 24 hours before she got word her father was OK.

In a family call later, her father told how he was sleeping on the floor in a crowded cell rife with insects at the Grand Tehran Penitentiary.

At first, she thought the Evin strike might prompt the government to release prisoners. But after seeing reports of mass detentions and executions, “all this hope is gone,” she said.

The war “just destroyed all the things the activists have started to build,” she said.