ROSH HANIKRA — Israeli researcher Dr. Mia Elasar and Haris Nicolaou of the Cypriot Agriculture Ministry stood together on a cliff overlooking the Mediterranean Sea in northern Israel on Tuesday and told a story about Maya, a Mediterranean monk seal and one of the rarest marine mammals in the world.

The seal was first spotted in Israel in 2010 and has been seen four more times since. In August 2024, in the middle of the war with Hezbollah, Israeli soldiers on patrol near the northern border with Lebanon spotted Maya again.

Maya is one of roughly 600-700 monk seals left in the world, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, though other estimates put the number even lower. The species is classified as endangered.

Elasar, who heads the Mediterranean monk seal research at the environmental nonprofit Delphis Association, recounted that when Nicolaou first arrived in Israel on Monday, he showed her photographs of female seals that he had tracked in Cyprus. One seal looked familiar and Elasar couldn’t hide her excitement.

“That’s Maya!” she exclaimed to Nicolaou.

By the scars on the seal’s face, Elasar recognized the mammal that, Nicolaou said, was known in Cyprus as Anassa, Greek for “mother of Jesus.”

Nicolaou, the coordinator of the Mediterranean monk seal monitoring program in Cyprus, said that the seal gave birth to a pup last year and then, “after she nursed her pup for five months, she took a holiday and came to Israel,” 240 kilometers (149 miles) away.

Elasar said that Maya has been observed in recent years splitting her time between Israel, Cyprus and Lebanon.

“We follow her on social media and were happy to learn that yesterday Maya was spotted off the coast of Lebanon,” the researcher said.

Monk seals travel in the eastern Mediterranean waters between Greece, Turkey, Cyprus and Israel.

Although these countries are often beset by wars, conflicts and closed borders, “the seals are free,” Nicolaou said.

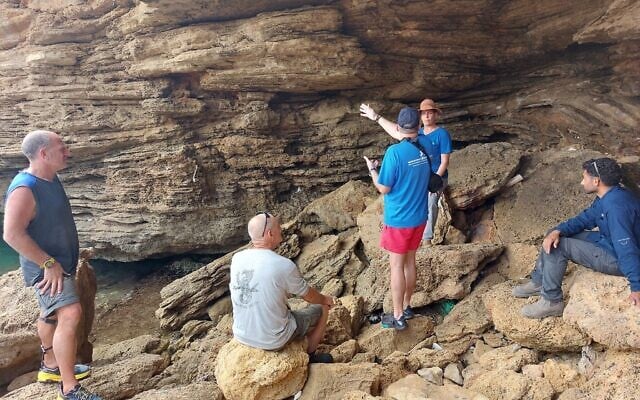

Delphis, which advocates for the protection of marine mammals in Israel, invited Nicolaou to consult on a project to restore two caves in the Rosh Hanikra area near Israel’s northern border with Lebanon. By renovating the caves to meet the seals’ needs, they’re hoping the seals might be encouraged to return to Israel — and to stay.

Researchers believe that one reason seals don’t stay in Israel is that they have nowhere to breed.

The cave restoration project was launched in March 2023, around the time a monk seal named Yulia was found on a beach in Tel Aviv and then vanished.

The Rosh Hanikra caves could be an ideal place because they are dark and quiet, which seals need, but the caves lack a dry bench or shelf where seals can rest while they breed and not be pulled out to sea.

Elasar explained the personal significance of the project to a group of journalists by sharing her own experience.

“I hadn’t been to this area in 18 months because of the war,” Elasar said as she walked along the rocky shoreline. “Being here isn’t something I take for granted.”

For months since October 8, 2023, the Lebanese terror group Hezbollah attacked Israeli communities and military posts along the border on a near-daily basis, with the group saying it did so to support Gaza amid the war there.

That war began the previous day, when thousands of Hamas-led terrorists invaded Israel, butchering 1,200 people and kidnapping 251 into Gaza.

Elasar, who lives in Rosh Hanikra, was evacuated along with 60,000 other residents from 32 communities in the northern region.

She moved six times during the war and returned to her home, which was damaged by bomb blasts, in January.

Marine life flourished during the war with Hezbollah because the shoreline and sea near the northern border were closed to humans. Elasar said that the abundance of fish, lobsters and other food might attract the seals to come back.

The seals weigh up to 300 kilograms (661 pounds) and need some five kilograms (11 pounds) of food each day. They’re hefty animals, which is part of the problem.

It’s almost impossible for the seals to climb up rocky ledges within the caves.

The cave restoration project is being carried out in partnership with the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, the Monk Seal Alliance (MSA), the Cypriot Agriculture Ministry’s Village and Environmental Development Department, and the Deutsche Stiftung Meeresschutz Foundation.

The contractor, Bar Marine Services, works with Delphis volunteers under the supervision of Nicolaou, who previously oversaw the restoration of 16 caves for seals in Cyprus.

The contractors placed bags of cement in the cave, which the researchers believe can be used by the seals to help them pass over the rocky ledges to reach a protected plateau in the back of the cave. There, a pregnant seal can remain dry even when the sea is turbulent and crashes against the rocks.

Seals normally have one pup at a time. The researchers have installed cameras to monitor the seals if they do make their way into the renovated cave.

“We’re excited but we’re waiting with patience,” Elasar said.

“The discovery underscores the importance of regional cooperation in conserving monk seals,” she said.

“No matter what is happening with politics on the outside, when researchers sit around the table, all we’re discussing is preserving monk seals,” she said. In fact, Israeli and Turkish researchers will soon publish a joint research study about monk seals.

The seals have “lots of enemies,” Nicolaou said. “Young animals are caught in fishing nets. They have collisions with boats. Tourists disturb them. If a young seal pup is disturbed and loses sight of its mother, it means certain death.”

In the past, a monk seal would spend her 10-month pregnancy lying on a beach. Today, there aren’t enough isolated beaches for seals to do that.

The animals have resorted to caves where they are safe and undisturbed.

Although there are 5 million tourists who descend on Cyprus each year, Nicolaou said, the government has been able to make five protected areas for the seals. He thought there were no monk seals at all until 2010. Now there are 22 seals living in six caves that Nicolaou helped to restore.

Elasar said she could talk “for an hour” about people’s dependency on the sea.

“As long as the ecosystem of the sea is stable, we can continue to live and get oxygen and food from its waters,” she said. “The monk seal plays a part in its stability and health.”

Moreover, she said, “With all the chaos and all the pain around us, it’s nice to hear about an optimistic story.”

“We always hear about species that are vanishing or being destroyed,” she said. “It’s rare to read an ecological story with a good ending.”