As a young boy growing up in Kermanshah, in western Iran, Payam Feili, now 40, would race to a shelter with his parents when air raid sirens pierced the air, signaling incoming Iraqi bombings during the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s.

In a surprising twist of fate, decades later, Feili once again found himself running for cover — this time as his native country launched ballistic missiles at his adopted city of Haifa last month in retaliation for Israel’s preemptive strike on Iran’s nuclear program.

A gay poet and political dissident who was arrested multiple times before he fled Iran, Feili made headlines in 2015 when he visited Israel and sought asylum in the Jewish state. Ten years later, he experienced the Israel-Iran war “as a child witnessing his parents fighting,” he told The Times of Israel.

“My family was there getting attacked,” he said. “I live here and I was under attack from the ayatollahs. It was a confusing situation.”

Yet, according to Feili, not only he, but millions of his fellow Iranians, saw the Israeli military operation as a beacon of hope, a sign that change might finally be possible in their country.

“Persian people inside Iran were under attack and still said thank you because they thought [Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali] Khamenei would go to hell,” he said, sharing a profound disappointment about the regime surviving the war.

Feili spoke with The Times of Israel in his small apartment in Haifa, surrounded by pictures, books and an affectionate cat.

During the interview, a projector beamed Iran International — an all-news Persian-language station based in London — onto a white wall in the kitchenette. The Islamic Republic designated the outlet a terrorist organization in 2022.

Payam said he watches Iran International a lot.

“I don’t like to watch the news, but I have to understand what is happening there,” he said.

Feili was born to a Kurdish family in 1985. He said religion was never part of his upbringing.

“Despite growing up in this Muslim Shia country, I did not receive any religious education, and my parents always encouraged me not to take part in any religious ceremony,” he said.

When he was a teenager, Feili moved to Karaj, a large city some 30 kilometers from Tehran.

Despite homosexuality being illegal in Iran, he was open about his sexual orientation. His book “I Will Grow and Bear Fruit… Figs,” which was eventually translated into Hebrew, started with the words “I am 21 years old. I am gay. I love the afternoon sun.”

In 2014, after spending 44 days imprisoned in a container by the Iranian authorities, the poet fled to Turkey, fearing for his life.

“When I left Iran, I was totally lost and looking for a land,” Feili recalled. “I thought, as an openly gay Iranian writer risking his life, I would get a lot of help from human rights organizations, but instead I was completely lonely.”

“The only person who actually helped me was Miri Regev,” he added.

Regev, a veteran Likud politician and Israel’s current transportation minister, was then serving as culture minister.

One of Feili’s books had been translated into Hebrew. Regev persuaded the Interior Ministry to grant the author a tourist visa to present his work in Israel – something that would have otherwise been impossible for the citizen of an enemy state.

The poet, meanwhile, was living in Turkey during a period that he described as “horrible.”

“I was just wandering from organization to organization, gay rights organizations, human rights organizations, just to find a place, to find a home,” Feili said.

“For two years, I never unpacked my suitcases, because I thought I was about to fly somewhere,” he noted. “Back then, it felt endless. In the end, it was okay.”

As happy as Feili was to get to Israel, life was not easy in the Jewish state. While he describes Israelis as very friendly toward him, it took him years to be granted refugee status.

“Meanwhile, I had to live like a criminal, working under the table, with no medical care,” he recalled.

During his first years in Israel, as Feili lived in Tel Aviv, he found himself entangled in heavy drug usage and lost two close friends to suicide.

The author described this period in “Madam Zona” (zona means “prostitute” in Hebrew), a memoir published in 2020.

“If I had not written my memoir, I could not recognize who I am,” Feili said. “I have to read myself. If I don’t, I am lost.”

The poet stressed that he does not want to complain, because both Israel and Israelis did a lot for him.

“I felt a lot of heart from the Israeli people,” he said. “They are warm. They love to host lonely people like me. And they did it. I will always appreciate it.”

Feili also stated that, with his refugee status, he now receives the same benefits as an Israeli citizen.

“The only thing I cannot do is to vote,” he said, joking that, with the current political climate, he is actually happy not to do it.

Feili said he chose to come to Israel in the hope of finding a sense of Middle Eastern kinship.

“I am not polite enough to be in Europe,” he joked. “I prefer it here. You don’t need to be so polite here.”

Despite his deep opposition to the current regime in Iran, Feili said he deeply loves his Persian identity.

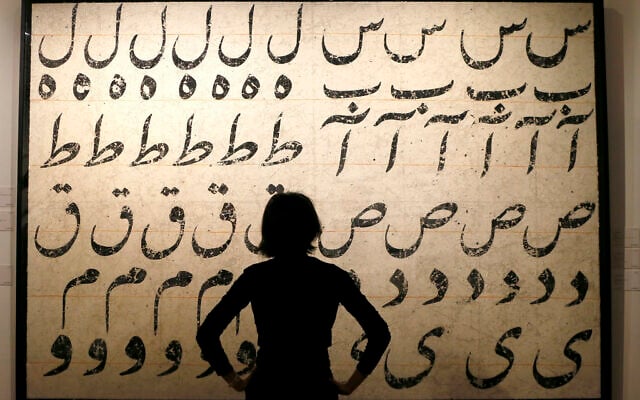

“No matter what, I am happy that Persian is my mother tongue because I am in love with the language,” he said.

He described writing as something as indispensable as breathing.

“Writing for me is a way to explain myself to myself,” Feili said. “This is not always a good position to be in, because it feels like having no explanation for your existence. I love that writing gives me the answers.”

For this reason, Feili never stopped composing, even during the Israel-Iran war.

“These ones, who have beheaded my dreams /Will one night hang my lineage from the gallows/ Surely, as stripped of all as they are/ At dawn they will hang all I have — and all I am,” reads one of the poems he wrote during the war.

The war started on June 13, after Israel began a sweeping assault on Iran’s top military leaders, nuclear scientists, uranium enrichment sites, and ballistic missile program to prevent the Islamic Republic from realizing its avowed plan to destroy the Jewish state.

Iran retaliated to Israel’s strikes by launching around 550 ballistic missiles and 1,100 drones. The attacks killed 28 people and wounded over 3,000 in Israel, while some 13,000 were left displaced from their homes. Regime-controlled Iranian media said 935 people in Iran were killed in Israeli strikes.

Feili said people in Iran are deeply disappointed with how the confrontation between Iran and Israel ended.

“After October 7, the Israeli government and even the US have been talking about killing the snake in Tehran,” he said.

“[The Israeli attacks] fucked all the atomic places, all the missiles places, they wounded the snake but did not kill him,” he lamented. “Now the snake does not have any power against Israel, but it has a lot of power against the Persian people.”

According to Feili, the situation in Iran is now more perilous for those who oppose the regime than ever.

“Even as people were under attack by Israel, in a horrible situation, they felt hopeful,” he said. “But now that [the regime] is just wounded, it will be even more dangerous.”

Feili said that he and millions of people are angry about it.

“I can’t say that it is everyone in Iran, but many,” he said.

Asked whether he believed the Iranian people could bring about a regime change on their own, Feili was skeptical.

“We need help,” he said. “Our hands are empty.”

According to Feili, Persians and Jews have a long history of mutual assistance.

“We helped the Jewish people to come back to Israel after the Babylonian exile,” he said, referring to how the Persian Empire allowed Jews to return to the land of Israel after it defeated Babylon in the 6th century BCE.

“It would be very beautiful if Israel could help us,” he added.

Reflecting back on his childhood experience of seeking shelter from bombing, the poet recalled how disturbing the sirens and booms were for him, as a child who could not even spell the word “war.”

“Now I am 40 and I understand what war is,” he said.

Feili explained that despite the fear, he found something beautiful in joining Israelis from all walks of life in the public shelter in front of his apartment.

“I went there and sat,” he said. “There were people, workers, old people, young people who whenever they got in, they started to joke. They started to laugh.”

“I thought it was both beautiful and sad, how they got used to being at war,” he noted.