After stints fighting in the Global War on Terror in the early 2000s, soldiers in the United States forces were increasingly diagnosed with neuropsychiatric conditions that evaded explanation. Slowly, researchers began to tentatively find a correlation to battlefield concussions.

“A lot of American soldiers were coming back with neuropsychiatric problems that were eventually linked to blast concussions. But it took until 2006 — a full five years — for the military to even begin screening for concussions. It took another five to six years for them to fully develop their traumatic brain injury (TBI) protocols,” Dr. Raquel C. Gardner, director of clinical research of the Joseph Sagol Neuroscience Center at Sheba Medical Center, told The Times of Israel.

According to figures released by the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center in the US and cited in studies, 413,853 US military service members were diagnosed with TBI between 2000 and 2019.

“I began studying and working in neuroscience against the backdrop of the Global War on Terror, which started in 2001. There was beginning to be an awareness of TBI and that this needed to be looked into,” Gardner said.

Before immigrating to Israel with her family in 2021, Gardner had a clinical research program focused on TBI at the University of California San Francisco. It was funded by the NIH, US Department of Defense and Veterans Health Administration.

TBI is another term for a concussion, which can be mild, moderate, or severe. While most people who suffer a concussion fully recover over time and with proper treatment and follow-up, some continue to be symptomatic.

When the war against Hamas broke out on October 7, Gardner was certain that Israel would start seeing a lot of combat-related traumatic brain injuries.

She was thinking mainly about invisible TBI — the kind where the injury is not apparent to the eye. No bullet or shrapnel has pierced the skull.

“We still do not know what the long-term effects of single or multiple occurrences of TBI are,” Gardner said.

Most times, TBI can’t even be seen by medical imaging. As a result, it is often not properly diagnosed or treated.

The challenge at the moment is to educate Israeli medical professionals, get them to screen the wounded for the condition and provide appropriate care. Gardner, who has set up a wartime TBI program at Sheba, admits that this is a big ask from the staff as they work nonstop to save soldiers from immediately life-threatening injuries.

In a recent interview with The Times of Israel in her office at Sheba, Gardner recounted how she and her partners at the hospital began on October 8 to set up war-related TBI initiatives. She was fortunately able to rely on aspects of the research program she transferred from UCSF. She also leveraged her connections with other TBI experts around the world.

As important as it is for the IDF and the Israeli medical system to get a better handle on TBI, Gardner emphasized that Israel is no further behind on this as compared to countries other than the US. She’s eager to move the research forward but also recognizes priorities and puts things in perspective.

“It took the US at least a decade to get somewhere with this, and it continues to do studies costing huge amounts of money. Israel is six months into an ongoing war for its survival,” she said.

The following are highlights, edited for brevity, from The Times of Israel’s conversation with Gardner.

The Times of Israel: Many people are familiar with the term concussion but have never heard it referred to as TBI. Can you provide some clarification?

Dr. Raquel Gardner: First there is an exposure. It can be a hit to the head, an acceleration or deceleration (a strong sudden head movement), or a blast wave that travels through the head and brain.

If the person feels and exhibits no symptoms immediately, then we say it is a sub-concussive event.

Some of my research has been on American football players who have suffered repeated sub-concussive events. This has been linked to something called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which at this point can only be diagnosed after death during a brain autopsy. This has also been seen in autistic children with head-banging behavior, victims of domestic violence and soldiers with head impacts from repetitive blasts.

Not everyone with repetitive sub-concussive events ends up with CTE. We don’t yet know why some people get it and some don’t. The repetitive sub-concussive impacts are necessary but not sufficient for developing the condition.

So what has to happen for one of the exposures to cause a TBI?

At least one of three things needs to happen after the exposure for there to be a clinical TBI diagnosis. One is a loss of consciousness for any period. Another is what we call peritraumatic amnesia, or a loss of memory immediately after the exposure. The final one is an alteration of consciousness, which is essentially confusion, disorientation, or repeated questioning. You can categorize the severity of the injury based on how bad the symptoms are and how long they lasted after the exposure.

If the symptoms are bad enough or lasted long enough, a head CT will be done. If blood is seen on the CT, that is another way to make a clinical diagnosis of TBI.

What we mostly see from modern warfare is concussion as a result of a blast that is CT-negative for blood and involves loss of consciousness or amnesia of less than 30 minutes. Usually, it’s either no loss of consciousness or for just a few seconds. These cases of TBI are therefore categorized as mild.

What are you doing at Sheba to address TBI during the war?

The first thing we did was draw from all the best TBI screening tools in existence — especially for high- and low-level blasts — and create our own validated tool in Hebrew to use with the soldiers in our rehabilitation units. Optimally, screenings should be done within 24 hours of the exposure, but that hasn’t been possible for us.

We asked the soldiers questions about what happened to them to determine whether they were exposed. If they were, we could use the screening information to make a clinical diagnosis. We also asked them about post-concussive symptoms. Among these are headache, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to sound, sleep difficulties, general fatigue, irritability and depression. Insomnia is almost universal among soldiers who have blast concussions.

What did you find?

We found that 60 percent of the first 50 soldiers we screened met the clinical criteria for concussion. Of the soldiers screened who had non-blast mechanisms of injury, only 25% had concussions. However, of the soldiers who were injured by a blast, 75-80% had a concussion. The screening is ongoing for soldiers in the rehab units and we are tabulating all the data.

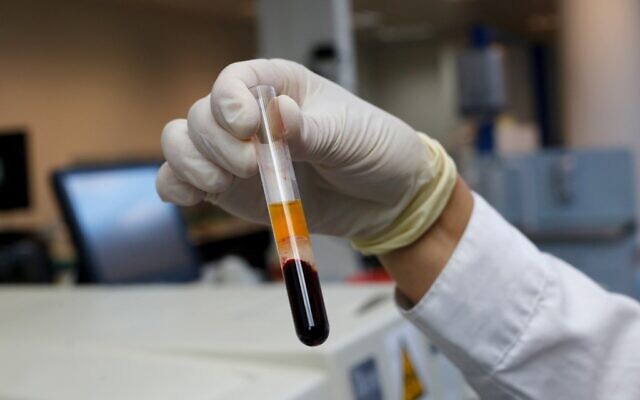

You were involved in studies that led to FDA approval last year for a blood test that can help diagnose TBI. How does that work?

The test detects two proteins in the blood. It is very good at ruling out intracranial hemorrhage with 99% specificity. But what we also know from our research studies, is that the protein levels elevate anytime there is an acute traumatic brain injury, even in a patient with a CT or even an MRI that does not show bleeding in the brain.

Immediately after October 7, we reached out to Abbot Laboratories asking them to distribute the test to us for what would be off-label use. They were not planning to distribute it to the Middle East, but they agreed. The test arrived here on January 1. We are in the process of validating it in our hospital laboratory, but in the meantime we are already doing the test on every soldier evacuated to our emergency room. We have found that every soldier who meets the criteria for a clinical TBI diagnosis also has elevations of these markers in their blood.

TBI and PTSD often go hand-in-hand because brain injury occurs in a very stressful combat situation. Soldiers may also be stressed from bodily injuries. Can this blood test help in differentiating the two conditions?

Yes. Let’s say a soldier is in a booby-trapped building and there is a blast. The soldier is affected by the blast wave and also sees that his friend who was fighting next to him has been killed. The soldier can exhibit concussive-like symptoms, such as confusion and disorientation, but this is not necessarily from a TBI. This can also be the way he is reacting to emotional trauma. The blood test can tell us whether he had a concussion or not.

What about soldiers who are exposed to repeated low-level blasts, such as those in the armored corps?

The US military is doing studies to try to determine the safe threshold of low-level blasts. We don’t know how this blood test we discussed can be used to predict who will go on to have chronic post-concussive symptoms or not. There’s a huge amount that we don’t know. We are already leveraging everything we know from the US military, but we need more manpower and resources to also study this here in Israel with the IDF. There needs to be a medical group here that champions this condition. It could be neurology, psychiatry, or physical medicine and rehabilitation.

How is the US military studying the effects of low-level blasts?

They are studying this in training settings. They have begun outfitting special forces units with blast gauge monitors. A company called Blast Gauge makes a three-sensor system that captures pressure and acceleration experienced in an explosive blast.

One sensor goes on the back of the neck, one on the chest, and one on the shoulder. Anytime there’s a blast, the sensors send information wirelessly to a tablet. The system stores information cumulatively showing how much blast pressure a soldier has been hit with over time. The system has its drawbacks and pressure wave dynamics are very complex.

Another system from a different company being tried out involves only one sensor that immediately shows the level of pressure from the blast exposure. The soldier can look at the gauge on his uniform and immediately see how much exposure they have had. The researchers have found that the behavior of the soldiers using this device has changed based on the readings. Even just a slight change of position can change the pressure exposure level.

How have the soldiers at Sheba diagnosed with TBI handled it?

We have found that the vast majority of them are dealing with it well.

The key is to educate the soldiers — and everyone else — about how to address the symptoms. We emphasize that there is no reason to suffer from the symptoms and that the patient should see their doctor because there are ways to effectively deal with them.

The most important thing is sleep, which is extremely important for neurological recovery and rehabilitation. If a person with a concussion has trouble sleeping, it is okay for them to use sleep medication prescribed by their doctor. Natural sleep is better, but medicated sleep is also an option in this situation. Just reassuring people with TBI that their chances for recovery are extremely high often makes them less anxious and enables them to sleep.

We don’t have a magic pill to fix brain injury. The most important thing we can do now is to diagnose, educate, and help people optimize their own recovery.