Sharifa Zuheirah, a woman in her 40s, has lived in her husband’s hometown of Bethlehem since the two got married years ago.

Since the start of the year, though, she has been returning more and more frequently to Nu’man, the tiny East Jerusalem hamlet where she grew up.

Her visits are driven by fears that at any moment the Jerusalem Municipality could demolish her mother’s house, which, like all homes in the village, has three demolition notices hanging over it.

“Since the demolition warnings were delivered, I come twice a week. I’m terrified the municipality will show up any day and destroy the homes,” she told The Times of Israel outside the house where her mother, a widow in her 70s, lives alone.

If the order is carried out against the homes, which mostly hug a single road on a hill in the far southeastern corner of Jerusalem, it will mark the first time an entire East Jerusalem village will have been erased by Israeli authorities.

According to the municipality, which began issuing the demolition orders in January, the approximately 45 structures in the hamlet were built without proper permits.

That is because Nu’man has already largely been erased by Israel, at least bureaucratically. Though the land it sits on is inside East Jerusalem, its residents have never been recognized as city residents, placing them in a Kafkaesque grey zone.

Despite being registered as West Bank Palestinians, the hamlet’s approximately 150 residents pay municipal taxes to Jerusalem. At the same time, they are excluded from its rights and services, including an approved city zoning plan, normally a prerequisite for being granted a building permit.

According to the city, Nu’man sits on land zoned for agriculture. It said enforcement actions were being carried out against “buildings constructed without permits after 1967, which make up most of the neighborhood’s structures.”

Israeli authorities regularly cite the lack of building permits for demolition orders carried out against Palestinian construction, whether in East Jerusalem or in parts of the West Bank under its civil control. Critics say Israel refuses to approve zoning plans or issue permits for Palestinian neighborhoods, forcing them to build illegally to house growing populations.

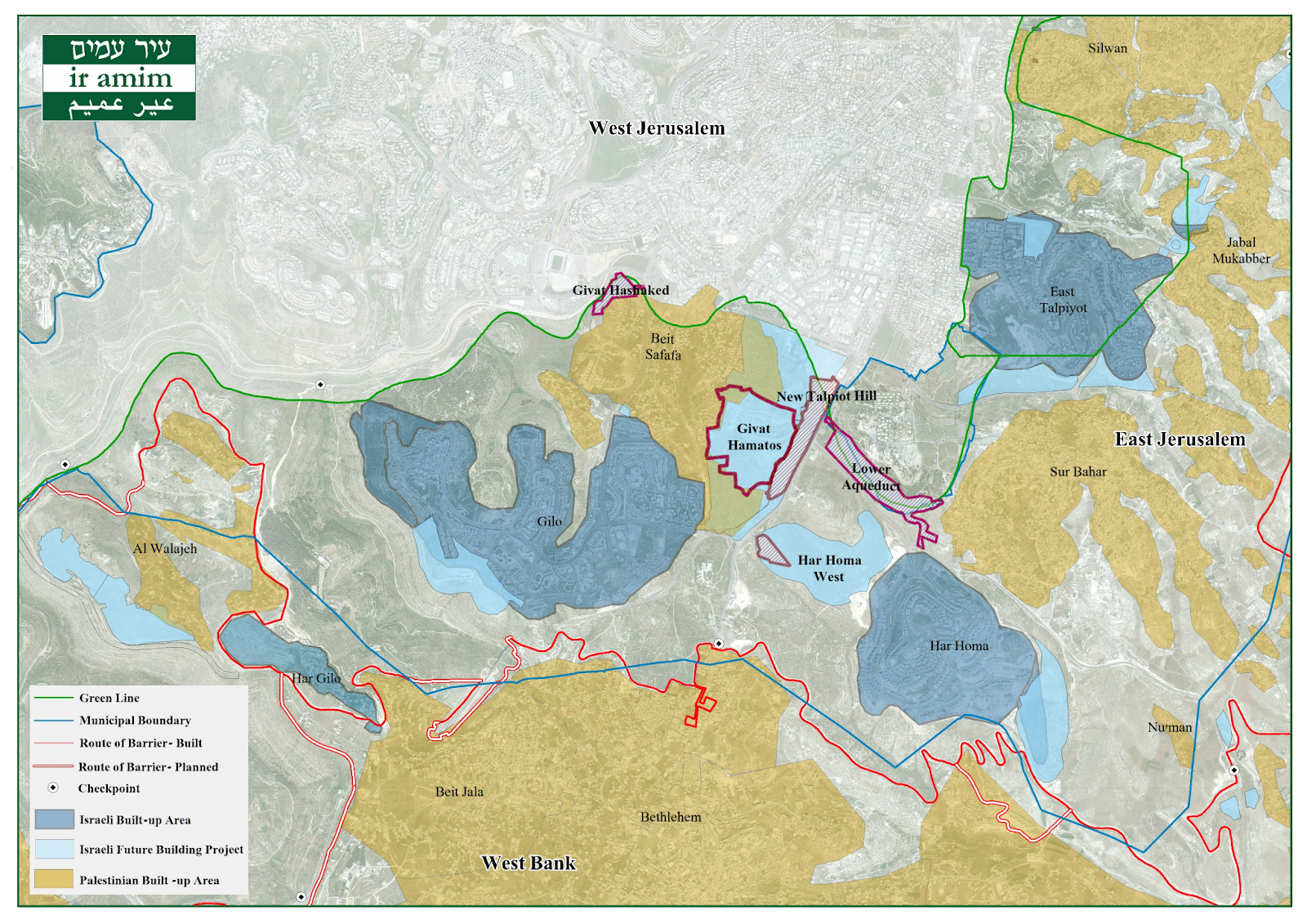

Such demolitions are on the rise, according anti-settlement NGO Ir Amim.

A report by the NGO found that 255 structures were demolished in East Jerusalem last year, including 181 housing units and another 74 non-residential units. The figure marked a 14% jump over the previous year.

After Israel captured the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan in the 1967 Six-Day War, When Israel captured East Jerusalem from Jordan in 1967 and declared the city unified, it also expanded the borders of the city well outside its urban footprint, encompassing villages far outside what would have been considered part of the city at the time.

The new Israeli military administration, which was also responsible for the West Bank, granted those living inside Jerusalem’s new borders permanent residency in Israel, entitling them to health care, welfare, and education — though not full citizenship or the right to vote in national elections.

Those living outside the city were registered as “West Bank Arabs,” with no rights in Israel.

For reasons Israel has never explained, Nu’man’s residents were included in the latter category, despite their homes being well within the city.

Nu’man resident Jamal Draawe told The Times of Israel that his grandparents first arrived in what is now the hamlet nearly a century ago, long before the establishment of Israel.

“They lived in tents and caves here, and in the 1940s they and others began to build homes,” he said. “In 1967, after the Israeli census, the villagers were classified as West Bank residents, not Jerusalemites. But people continued building houses and living here.”

Until the 1990s, children from Nu’man studied at the closest school in Umm Tuba, an East Jerusalem neighborhood whose residents hold Israeli permanent residency. Back then, the boundaries between East Jerusalem and the West Bank were open, and few paid attention to the bureaucratic distinctions.

Everything changed in 1993, with the creation of the Palestinian Authority under the Oslo Accords. That year, those classified as West Bank residents received green identity cards from Ramallah and became eligible for Palestinian-provided services such as education and health care.

Nu’man’s children were barred by Israel from attending East Jerusalem schools, forcing them to study in the West Bank town of Beit Sahour, near Bethlehem.

Residents also started receiving water and electricity from the PA rather than from the Jerusalem Municipality.

Nonetheless, in 2019, residents started receiving notices from the Jerusalem Municipality demanding the payment of property taxes, on the grounds that their homes lay within municipal boundaries — despite the fact that they receive no services from Israel or the city, including education, health or even garbage collection.

“From 1993 until 2019, a garbage truck from the Palestinian Authority entered once a week with Red Cross coordination,” Draawe recalled. “But the municipality demanded we pay the tax and stopped the truck from coming.”

Since then, each household has had to burn its waste in makeshift pits. Walking through the village, one can see the smoldering sites between homes. Residents were also billed retroactively for decades of unpaid taxes, amounting to tens of thousands of shekels each.

Today, every household pays around NIS 5,000 ($1,460) a year in property taxes to the municipality. Those who fail to pay face asset seizures and travel bans.

In response to a query from The Times of Israel, the Jerusalem Municipality said in a statement that tax levies had no connection to a building’s permit status.

“Every structure within the city’s boundaries is subject to tax payments, whether it was built legally or not,” it said.

In the early 2000s, Israel cut off the road linking Nu’man to East Jerusalem as it constructed the West Bank security fence, even as it included Nu’man on the same side of the barrier as the rest of Jerusalem.

A High Court petition filed by villagers against the route of the fence at the time was rejected on the grounds that residents were there illegally, since they were registered as West Bank Palestinians despite physically residing inside Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries, a paradox created by Israel’s own decision in 1967.

Since then, the only way in or out of Nu’man has been through a checkpoint designated exclusively for village residents, which links the village to a road running through the West Bank, though it sits mere steps from a separate checkpoint into Jerusalem.

“In 2006, when the wall was completed, the army compiled a list of everyone in the village. Since then, only those on the list are allowed through the checkpoint,” Draawe told The Times of Israel.

Non-residents must apply for a permit from the IDF, but approval is not always granted, and even when it is, entry is not guaranteed. The Times of Israel was able to access the village with Ir Amim, which had requested advance approval for entry. Those seeking to enter had to wait by an unmanned gate until guards stationed at the nearby checkpoint into Jerusalem allowed them in.

A villager who asked to use the alias Ahmad said the restrictions on entry have grown even stricter since October 7, 2023, amid Israeli fears that West Bank Palestinians could carry out an invasion similar to Hamas’s assault from Gaza. “Before October 7, outsiders could sometimes walk into the village. Today, they don’t allow it at all,” he said.

Two years ago, Ahmad was granted permanent residency in Israel, joining the small number of Nu’man residents to have been granted the status, typically through marriage to partners from East Jerusalem. The move, which can take decades to process and requires extensive legal proof of residence, came 35 years after he married his wife.

In December 2024, all 150 residents petitioned the Jerusalem District Court to grant them permanent residency like other Palestinians in East Jerusalem. The court has yet to rule.

Draawe, who carries a green Palestinian Authority ID, cannot enter Jerusalem and so works as a clerk for the PA.

“I earn a salary from the Palestinian Authority and hand it straight to the Jerusalem Municipality,” he said with a bitter smile.

Nu’man’s residents say the first time they learned that their homes were officially inside Jerusalem was in 1993, when municipal inspectors arrived and demolished a covered parking structure, saying it had been built without a permit. Only then did villagers realize that despite being classified as West Bank residents, their homes were inside Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries and subject to city planning regulations.

Several new houses had been built in the hamlet during the 1990s, but they too were demolished by the municipality for lack of permits. Since then, villagers say, no new construction has taken place. The approximately three dozen stone structures making up the village are all more than 35 years old.

Under Israeli law, including in Jerusalem, building permits require an approved master plan for the area. Unlike in West Jerusalem neighborhoods, Nu’man has never had such a plan approved. In 2006, residents submitted a request for one, but the city rejected it, arguing the land was zoned as agricultural and “unsuitable for residential use.”

A city-wide masterplan designates part of the hamlet’s land as a city park, and the rest as “open area.”

Residents submitted a new request for a zoning plan in recent months, but have yet to receive a response. What they have received, however, are three official warnings that their homes stand to be demolished.

Reut Maimon of Ir Amim, which has been assisting the villagers, sees the warnings as part of a deliberate effort to force people out.

“Demolishing these homes is not only unjustified, it is a planning crime that endangers the future of dozens of families. Across East Jerusalem we see Palestinians being uprooted through bureaucratic means, and Nu’man is no different. They are being pushed out of the city through so-called ‘legal’ steps,” she told The Times of Israel.

The municipality has not formally declared an intent to evict Nu’man’s residents. In June, it announced plans to expand the nearby Har Homa neighborhood over an additional 59 dunams (14.5 acres), adding 476 apartments in several 8-12 story buildings, as well as commercial structures, a school and more. The city has not published plans for the project, but existing zoning maps do not show the new neighborhood reaching Nu’man’s homes.

The Jerusalem Municipality said there were no plans to put Israeli homes where Nu’man stands now.

“The land on which the houses were built is not zoned for residential purposes. The municipality has no intention of building in the area,” it said in response to a question from The Times of Israel.

Ahmad described a sense of despair in the village as demolition looms. He fears that most villagers, who hold green PA ID cards, will be expelled once the houses are gone.

“We’re under pressure. We don’t know our future here. The situation is very hard, very dark,” he said. “It could be that tomorrow they come and destroy our homes.”

Draawe insisted that he would never leave: “Even if they demolish my house, I won’t go. Where would I go? This is my land, my father’s and my grandfather’s.”