Nine months into his 10-year term, Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi Kalman Ber is seeking to breathe new life into the Chief Rabbinate, an institution largely defined by its resistance to change.

Revamping the fusty body would be no simple task, likely requiring challenging long-held power structures, but Ber approaches the process as a uniter rather than a divider.

As the body that largely oversees the Jewish character of the state, the Rabbinate wields sweeping influence over Israeli life. It sets kashrut standards in both the public and private sectors, holds exclusive authority over Jewish marriage, and directs the rabbinical court system responsible for several Jewish issues, including divorce and conversions.

But while Ber envisions changes to many of these areas, he is no revolutionary. A Rabbinate stalwart with a reputation as a peacemaker, he is steadfast in his belief that most problems can be solved only by working behind the scenes and avoiding messy public fights.

Ber sat down with The Times of Israel for a wide-ranging interview during the so-called Three Weeks, a time of mourning and communal reflection preceding Tisha B’Av, when themes of unity and healing societal divisions are often emphasized. The fast day, which marks the anniversary of the destruction of both the First and the Second Temple, begins Saturday night and ends Sunday night.

“It is not enough to call someone my brother,” Ber said. “Every night, before going to sleep, everyone should reflect on whether they have done something for someone outside their own community.”

But to succeed, he stressed, people need to move from words to action.

For Ber, as chief rabbi, that means embracing Jews of all stripes and making the Rabbinate accessible to as wide a swath of people as possible.

It is with that spirit of that the chief rabbi says he wants to implement changes to the way the rabbinate handles marriages, reversing a trend that has seen a growing number of Israeli couples opt out of wedding ceremonies through the Rabbinate – the only way for Jews to legally wed in Israel.

“One of the parameters to measure my success is to bring more couples to get married through the Rabbinate,” the rabbi said, adding that he has already assembled a team to come up with a working plan.

Ber also vowed to soon roll out a kashrut reform that he says will cut bureaucracy, increase selection and lower prices.

For many Israelis, the Chief Rabbinate represents a problematic or at best irrelevant institution, with over 50 percent of the public not accepting it as a religious or spiritual authority, according to a 2024 Israel Democracy Institute survey.

Ber defended the need for a Rabbinate and for the country to maintain its Jewish character, while stressing the importance of personal religious freedom.

“The state must have a Jewish character, because your father and my father wanted to come here because this is a Jewish state,” he said. “On a private level, everyone can do what they want, and, oy vey, I would be the first to protest if someone was told what to do.”

During the interview, Ber both stressed his close connection with many secular Jews and his aspiration to reach out also to Jews in the Diaspora. However, he was harshly critical of non-Orthodox Jewish movements, describing them as challenging “the core foundations of our religion.”

While his comments appeared to single out Reform Judaism, many Orthodox Israelis often use “Reform” as a catch-all for any non-Orthodox stream, reflecting a lack of familiarity with the array of Jewish schools of thought that have proliferated in the Diaspora but remain largely outside the Israeli mainstream.

The rabbi offered a Jewish perspective about the war in Gaza and on the need for Israel to be a light unto the nations in the context of protecting Druze in Syria.

Asked whether he considered the war in Gaza to be a milhemet mitzvah, a concept in Jewish law denoting a divinely sanctioned war that Jews are obligated to fight, Ber said that there was no doubt that a war of Israel against an entity that aims to destroy it should be considered as such.

Still, ultra-Orthodox leaders have steadfastly refused to forgo the decades-long blanket exemptions from army duty traditionally afforded to the Haredi community. The Supreme Court’s declaration that the practice is illegal has spurred the Haredi community to seek controversial legislation enshrining the exemptions in law rather than compromise on the issue, turning the problem into an explosive matter with the potential to bring down Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government.

Ber declined to offer an opinion on the draft crisis.

“Today we have a problem and we in the Chief Rabbinate are trying, in [private] ways, not in the media, to solve the problem,” he said. “I was a city rabbi for many years, and I saw that many things can only be solved when they are addressed behind the scenes, not in the media. Otherwise, there is no chance.”

Still, Ber said that he was completely confident a solution would be found, even though he acknowledged he did not know how long it would take.

The rabbi has long presented himself as a bridge with the ability to connect different worlds.

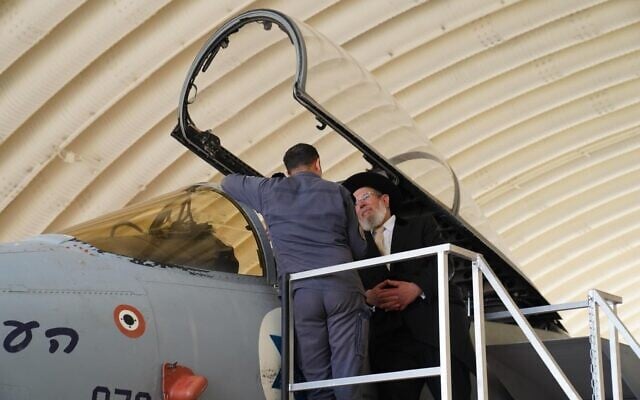

A descendant of prominent rabbis from both Hasidic and non-Hasidic streams, Ber was born in Tel Aviv in 1957 and learned and later taught in national religious institutions, including Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavneh, a yeshiva where young men combine Torah study and army service.

Ber himself served as a combat soldier in the Nahal Brigade. Of his two sons, one has also already served in the army, and the other is currently learning Torah full-time but plans to draft in the future.

In 2014, Ber was appointed chief rabbi of Netanya, where he maintained good relations across communities, from the Sanz Hasidic group, which has a significant presence in the coastal city, to its many secular residents.

In October, the 150-member committee responsible for appointing the chief rabbis — comprising roughly 80 rabbis and 70 public officials — chose him over religious Zionist hardliner Rabbi Micha Halevi.

His selection was made possible by the support of a broad coalition that included the ultra-Orthodox United Torah Judaism party, the moderate national religious rabbinical organization Tzohar, and many secular committee members. Halevi, by contrast, was backed by Bezalel Smotrich’s Religious Zionism party and the Sephardi Haredi party Shas, which has wide influence over the chief Sephardi rabbi.

Ber currently serves as the head of the Chief Rabbinate Council, the body advising all governmental bodies on Jewish issues, while his Sephardi counterpart, Chief Rabbi David Yosef, serves as the President of the Grand Rabbinical Court, overseeing the rabbinical courts in the country. After five years, they are set to switch roles.

“A rabbi cannot be sectarian,” Ber said during the interview. “Just as the president of the state may come from a political party but must rise above partisanship to serve all citizens, so too must a [chief] rabbi transcend divisions. If he remains only a rabbi for his own group, he fails in his mission. To truly fulfill his role, a rabbi must be a rabbi for everyone.”

The following interview was conducted in Hebrew and translated into English. It has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

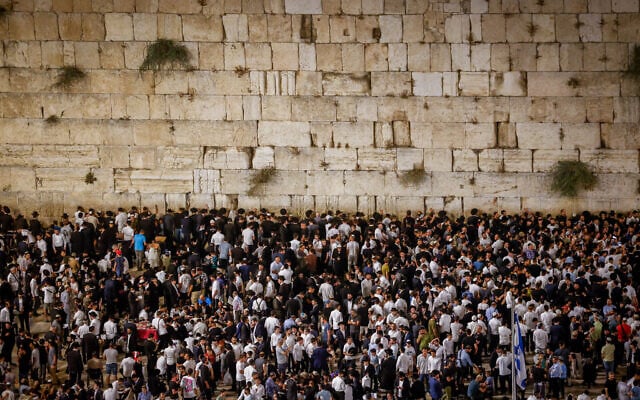

The Times of Israel: We are in the middle of the Three Weeks. What should Israelis be thinking about as we approach Tisha B’Av?

Rabbi Kalman Ber: The Talmud says that the First Temple was destroyed because of idolatry, sexual immorality, and the shedding of blood, the three gravest transgressions [according to Jewish law]. The Second Temple was destroyed because of baseless hatred. The Talmud asks: What is worse? The answer points out that after 70 years, the First Temple was rebuilt, while we are still waiting for the Second Temple to be rebuilt. This means that baseless hatred is something much more terrible.

What was this baseless hatred? [At the time of the Second Temple] everyone was serving God according to God’s will, but if someone practiced differently, they were viewed as a rodef [a pursuer of another Jew, who it is permissible to kill], an apostate, or a non-Jew.

Peace, the opposite of baseless hatred, is selfless love; it does not mean that everyone has to think in the same way or be in the same way, but we must leave room for each other.

In the weekly Torah portion of Pinchas, we recently read, “Let Hashem appoint someone over the community” [Numbers 27:16]. Rashi says that this is a leader who knows how to accommodate each spirit and each individual. What does it mean? That he agrees with everyone? I think that what he means is someone who knows how to include every person. Today, this is the most important thing that we need.

Before the [October 7] war, we were in a terrible place — a real war between brothers. The war has, in many ways, brought us closer together. This needs to continue. How? It is not enough to call someone “my brother”; we need to take care of everyone, even those who are not from our community.

I will tell you a story. A month after Simchat Torah [October 7, 2023], I was invited to join a visit to the Gaza periphery. We visited several places, and in the end, we went to Kfar Aza, the most devastated community.

There, a man approached me and said, “I’m a staunch atheist, and if you had come here before October 7, I would have preferred to see you outside our gate.” That wasn’t easy to hear. But then he added, “Now, I want to ask you for a big hug — and if you don’t mind, a selfie.” I asked his name and agreed, but I also asked him: “You’re still you, and I’m still me — what changed?” He replied, “I’ve seen what [religious people] are doing here in Kfar Aza, and what you’re doing in Shfayim, where I’ve been evacuated to. And I understand now — we really are brothers.”

I’ve learned that truly connecting with someone takes more than words — it means showing up for them and taking action.

The Jerusalem Talmud points to a striking paradox in the Bible: during the reign of King David, many fell in battle, while under a wicked king, no one did. Why? Because under the evil king, the people were united — while in David’s time, they were divided. As we approach Tisha B’Av, the message is clear: what we need is not unity in words, but unity in action.

Every night, before going to sleep, everyone should reflect on whether they have done something for someone outside their own community.

How do you view the role of chief rabbi?

First of all, the Chief Rabbinate takes care of some core issues, kashrut, marriage, agunot [women chained in their marriages], and so on.

However, beyond that, a chief rabbi must also be a beacon for Judaism and Torah. [The first chief rabbi of Mandatory Palestine] Rabbi [Abraham Isaac] Kook wrote upon establishing the Chief Rabbinate that its mission is to bring the light of Torah to every individual.

In these days since the war began, I can tell you that the thirst for Torah, for faith, for Judaism, is immense. People are eager to hear these teachings. As we approach the month of Elul, there is a lot we want to do. In his time, Rabbi Kook launched what he called a “rabbis’ journey,” traveling by donkey and horse to reach communities across the Land [of Israel]. That spirit must continue — not on horseback, but with the modern tools at our disposal: Shabbatons, educational gatherings, and more. On the Shabbatot when I’m not at home, I strive to be with the people of Israel — all of them.

In your first interview after being elected, in the national religious newspaper Makor Rishon, you described yourself as both Zionist and Haredi. Why was it important for you to emphasize that dual identity?

It is written of Queen Esther that she found favor in all those who saw her [Esther 2:15]. The Sages explain that this means she knew how to speak to every group so that they would feel she could represent them.

A rabbi cannot be sectarian.

Just as the president of the state may come from a political party but must rise above partisanship to serve all citizens, so too must a [chief] rabbi transcend divisions. If he remains only a rabbi for his own group, he fails in his mission. To truly fulfill his role, a rabbi must be a rabbi for everyone.

For some people in Israel, the Chief Rabbinate is a problematic institution, either because it represents religious coercion or because they have had bad experiences interacting with it.

The people of Israel returned to their land to be the people of Israel. The state must have a Jewish character, because your father and my father wanted to come here to live in a Jewish state. This is not religious coercion. On a private level, everyone can do what they want, and, oy vey, I would be the first to protest if someone was told what to do in their life, but the state needs to be Jewish.

At the same time, as someone who was a city rabbi for a long time, I know how important it is to make everyone feel welcome.

What do you think of the war in Gaza? Some people have called it a milhemet mitzvah, a divinely commanded war. Do you agree? How do we as Jews reconcile the war and the terrible devastation it creates with the idea that every person is created in God’s image?

I need to say, first of all, that Judaism is not against Islam, is not against Christianity, is not against any other religion. On the contrary, [influential medieval commentator] Rambam writes that the Holy One, blessed be He, created Islam and Christianity because they also advance the idea of monotheism, of one God.

However, we are against those who want to kill us. In the language of Rambam, a milhemet mitzvah is a war to save Israel from an enemy who attacks them. And against those entities that want to kill and eliminate us, for sure, we are talking about a milhemet mitzvah. We hope, we pray to the Creator of the Universe that He will help us so that we can win over all of them.

For those who do not try to destroy us, we do not have any issues with them; on the contrary, we want them to live in peace.

This brings us to the question of the draft crisis.

I will answer. First of all, Torah learning is very important. Our Sages say that during [King] David’s wars, David sat and studied Torah, and Yoav was his general [who did battle], and they complemented each other; otherwise, they would not have won [Sanhedrin 49a]. You need both. Today we have a problem and we in the Chief Rabbinate are trying, in [private] ways, not in the media, to solve it.

As a city rabbi, I saw that many things can only be solved when they are addressed behind the scenes, not in the media. Otherwise, there is no chance.

So you believe that there will be a solution? And how long will it take?

For sure. I don’t know how long it will take, but there will be a solution, God help us.

You served in the army. Can you share something about your experience?

Army service means many things, but one aspect I want to highlight is how it allowed me to connect with a wide range of Israeli society — people I likely would never have encountered. I was exposed to many things, many conversations, deep conversations, with different people, different groups, and even a different language.

Right now, one of the most pressing issues weighing on Israeli society is the plight of the hostages. Do you support a hostage deal?

We are all praying for the hostages, we worry for them, and we want to do everything in our power so that they will be freed.

About a deal, when the Jerusalem Temple stood, certain decisions were made by the Sanhedrin, a [legislative and judicial] body of seventy people.

I don’t think it’s appropriate for someone like me — who isn’t privy to all the details or the confidential information available to the prime minister and cabinet members — to offer an opinion on such a complex issue. In my view, it’s neither serious nor responsible to speak publicly on matters without a complete understanding. And this, after all, is one of the most difficult questions — one that, in another time, would have rightly been brought before the Sanhedrin.

Why was it important for you to speak out about the Druze?

On Sukkot, the Jewish people bring 70 sacrifices, which the Sages teach are offered on behalf of the 70 [gentile] nations of the world. This reflects our belief that the other nations matter — that we want the whole world to live in peace, “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and nation shall not lift sword against nation” [Isaiah 2:4].

Speaking specifically about the Druze, it is heartbreaking to witness the world watching in silence as horrific atrocities unfold — acts that evoke other horrible events in human history when the world also sat in silence.

The Druze did nothing; they were just born Druze. For that, they have suffered murder, humiliation and torture.

The Rambam writes that breaking a covenant is a desecration of God’s name. The Druze are with us, and while they did not formally sign a pact, they have a covenant with us, they enlist with us, and they die in battle with us. If we do not take care of our allies, this will be the most tremendous desecration of God’s name.

This is the reason why speaking up has been important to me. We are an ethical people, a light unto the nations, and we must keep our covenants.

I’d like to raise a few issues and hear your thoughts on the current situation, or changes you think should be made — beginning with the topic of kosher certification.

We are working on implementing a reform that will decrease the bureaucracy and increase the number of kosher products on offer. The idea is for the Chief Rabbinate to continue to oversee the system, and even boost supervision through technological means, but allow for more competition.

In Israel, the cost of living is higher than in other places for many reasons not connected to the Rabbinate. Our idea is that kashrut should not represent one of the problems from this perspective.

What about marriage and divorce in Israel?

This is really a critical point for me.

While the number of couples registering for marriage at the Rabbinate is rising, the number of those marrying outside the Rabbinate is also growing.

This is a project I am actively pursuing. It should not be the case that couples who can marry in Israel end up getting married in Cyprus.

I believe one key measure of my success is increasing the number of couples who choose to marry through the Rabbinate. I’m not referring to couples facing difficulties [because their Jewish status is not recognized by the Rabbinate], but to ordinary couples — and even for couples who have issues; with great care, some can be resolved.

It’s also possible that the Rabbinate hasn’t done enough public outreach on this matter. To address this, I have already assembled a team to develop a plan.

How do you view the status of conversions?

Conversions in Israel fall under the authority of the president of the Grand Rabbinical Court, so I prefer not to comment on that matter.

Regarding conversions outside of Israel, we recognize all conversions performed by approved rabbinical courts, and we have a committee dedicated to evaluating and recognizing such courts.

Do you see problems in the system?

Obviously, we verify who is responsible for the conversion and ensure it is real, but we recognize conversions every day.

In Israel, there are dozens of cities without a chief rabbi, and their appointment has raised controversies.

It is crucial to appoint rabbis who truly fit the communities they serve. A rabbi represents Judaism and can have a significant influence, but to do so effectively, they must be connected to the local population. Each city has its own unique character.

Currently, around 40 to 45 cities — nearly half the country — lack a city rabbi. The responsibility for these appointments lies with the Ministry of Religious Services, not the Rabbinate, and I urge them to expedite the process.

Another topic that has been in the spotlight later is the appointment of new dayanim (rabbinical judges). A Haredi newspaper recently published some leaked recordings that suggested you have been very concerned about it.

This matter also falls outside of my jurisdiction, so I am not going to comment.

How do you view ties with non-Orthodox Jewish movements?

I have no personal issue with any individual; a person is a person, and I love everyone. However, the Reform movement challenges the core foundations of our religion. A fundamental belief in our faith is that the Torah given by Moses is unchangeable. While we can interpret the Torah, we cannot contradict it.

For the Reform movement, Shabbat is defined by what feels comfortable to them; for me, I observe what is fitting for the Creator of the world. I adapt myself to the Creator, not the other way around. This is the essential difference between the Orthodox and Reform movements: who serves whom.

I have wonderful relations with secular people.

I make a distinction between the movements and the individuals. I love everyone, but I cannot recognize the movement.

What do you think of the Supreme Court ruling about allowing women to take the Rabbinate exams?

This is an eight-year-long story. [The petitioners] wanted women to take the exams. The Chief Rabbinate argued that we are not an academic institution that tests knowledge; we are not even a yeshiva, we are an institution that ordains rabbis. Since women aren’t [rabbis], we said that a different framework to test and certify them should be established, but not through the Rabbinate. The court decided that the Rabbinate needs to do it.

We, along with the Chief Rabbinate Council and the [Sephardi Chief Rabbi David Yosef], will convene to discuss and decide on our next steps, including whether we still have a say. Now that this [ruling] is here, we’ll make it happen. But the point here is that the Rabbinate argued that we are not a university or a yeshiva. We have nothing against women, God forbid.

So what do you think of women who want to learn and their status?

Wonderful. A woman who wants to learn can learn, can be tested, and can receive [certification]. We are in favor.

What is your message for Jews in the Diaspora?

They are deeply significant to me. The Chief Rabbinate has considerable influence over Diaspora Judaism, and it is important for me to try to be a positive influence there. Diaspora Jewry is developing.

Most Jews abroad feel a strong connection to Israel and to the prophetic vision that brought us here, so Judaism and the voice of the Rabbinate from the land of Israel must shine outward to the entire Jewish world.