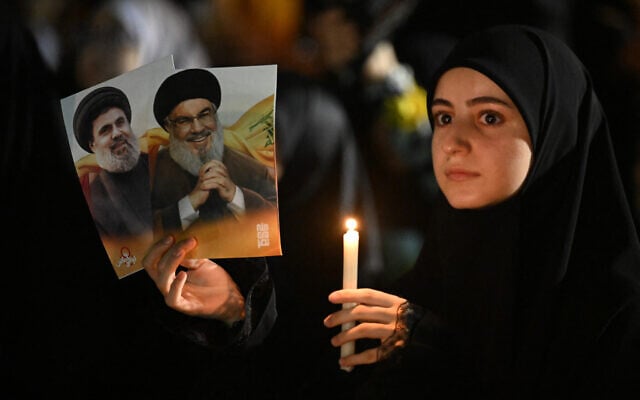

Lebanon’s Iran-backed terror group Hezbollah on Saturday will commemorate one year since its longtime leader Hassan Nasrallah was killed by Israel.

Crowds are expected to gather in Hezbollah strongholds in the southern suburbs of Beirut, Lebanon’s south and east. The group’s secretary-general, Naim Qassem, who took over a month after Nasrallah’s killing, will make an address.

Tensions over the commemoration have been mounting this week, particularly after Hezbollah projected the portraits of Nasrallah and his slain designated successor, Hashem Safieddine, on the famed towering rocks off the coast of Beirut.

Despite orders to the contrary by Lebanese Prime Minister Nawaf Salam and the Beirut governor, the display went ahead, angering Lebanese opponents of Hezbollah who said the cliffs should not be used for political displays.

On the evening of September 27, 2024, a string of Israeli bunker-busting bombs on a Hezbollah complex in Beirut’s southern suburbs killed Nasrallah, who had led the powerful Shi’ite terror group for more than 30 years.

Israel’s ensuing air and ground campaign in Lebanon prevented a formal burial for Nasrallah for months. Followers, including his son, have since flocked to his grave to pray.

Nasrallah’s killing came as Israel escalated operations in Lebanon in a bid to ensure the safe return home of some 60,000 northerners displaced when the terror group, unprovoked, began launching near-daily attacks on border communities starting October 8, 2023 — a day after fellow Iran-backed group Hamas invaded southern Israel, sparking the war in Gaza.

The Israel-Hezbollah war ended with a November 27 ceasefire that required the terror group to cede its arms in southern Lebanon to the state. Israel has continued striking the terror group, accusing it of violating the agreement.

The deal also required Israel to vacate southern Lebanon within 60 days, but Israel has since retained control of five strategic points inside Lebanon despite Beirut’s demands that Israeli troops withdraw.

The war and Nasrallah’s death dealt huge blows to Hezbollah. His heir-apparent and cousin, Safieddine, was killed three weeks after Nasrallah in another massive Israeli strike in Beirut. By December, Hezbollah’s Syrian ally Bashar al-Assad was toppled.

And in January, Lebanon swore in a new president, Joseph Aoun, ending a two-year vacancy in the post. Aoun, the former Lebanese army chief, has vowed to maintain a state monopoly on arms — a veiled threat against Hezbollah, the only Lebanese armed group not to surrender its weapons to the state after the 15-year Lebanese civil war ended in 1990.

Now, pressure is swelling in Lebanon on the terror group to disarm — a demand Hezbollah has rejected.

Despite the blows Hezbollah has sustained, a senior Hezbollah political official told The Associated Press that the terror group was rebuilding.

“The loss of this leader was a very painful blow to Hezbollah,” said Mohammed Fneish in the run-up to Saturday’s anniversary of Nasrallah’s death.

“However, Hezbollah is not a party in the usual sense that when it loses its leader, the party becomes weak,” he said. “In a relatively short period of time, it was able to fill all the positions it lost when (leaders) were martyred, and it continued the confrontation.”

An Israeli military official, speaking anonymously in line with regulations, said in a statement that Hezbollah’s “influence has declined considerably” and that “the likelihood of a large-scale attack against Israel is considered low.”

But the statement added that “the organization is attempting to rebuild its capabilities; efforts are limited but expected to expand.”

The military declined to comment on how much of Hezbollah’s arsenal of missiles and drones Israel believes remains intact.

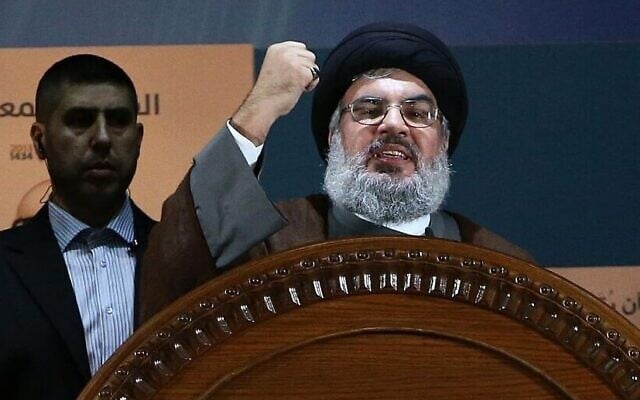

Nasrallah became secretary general of Hezbollah in 1992, aged just 35, after his predecessor, Sayyed Abbas al-Musawi, was killed in an Israeli helicopter attack.

With his fiery speeches, Nasrallah swiftly became the public face of a once-shadowy group founded by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards in 1982 to fight Israeli forces that had invaded Lebanon that year with the stated goal of stemming rocket attacks by Palestinian terror cells on northern Israel.

Nasrallah was at the helm when Israel withdrew from Lebanon 18 years later, and he declared a “Divine Victory” after the 34-day Israel-Hezbollah war of 2006, which was sparked when the terror group ambushed Israeli troops, killing three and abducting two who were later returned dead.

As Hezbollah under Nasrallah grew to become Lebanon’s most influential political and military force, it also developed a regional role as the spearhead of Iran’s so-called Axis of Resistance regional network of anti-Israel proxies, including Hamas in Gaza, the Houthis in Yemen, and, formerly, the Assad regime in Syria.

Hezbollah’s Lebanese critics have accused the group of giving Iran undue influence over Lebanon’s internal affairs, and of inviting Israeli attacks on Lebanon.

Meanwhile, the growing pressure on Hezbollah to disarm, and delays in reconstruction of areas battered in the most recent war with Israel, have left many in Hezbollah’s Shi’ite base feeling that there are attempts to marginalize them.

Lebanese political writer Sultan Suleiman said that feeling contributed to the base rallying and an overwhelming victory by Hezbollah and its allies in this year’s municipal elections in its traditional political strongholds.

Some who originally favored disarmament have reassessed.

“There’s a portion of this community that was psychologically worn down after this war, and started saying, fine, let’s give up the weapons and we’ll be able to relax,” Lebanese journalist Jad Hamouch said. “But after they saw how Israel is behaving in the region, now they’re saying, no, we want to keep the weapons.”

A Western diplomat who spoke on condition of anonymity in order to speak freely said the Lebanese state is caught in a catch-22 regarding its decision to disarm the group.

The cash-strapped and understaffed Lebanese army, where many soldiers work second jobs to make ends meet, is ill-equipped to face a force of battle-hardened and better-paid fighters who also, in some cases, come from their own communities, he said.

“I don’t see any coming back on this (decision), but I don’t see how it will go forward either,” he said.