BEIRUT, Lebanon — Hezbollah has long been considered Iran’s first line of defense in case of a war with Israel. But since Israel launched its massive barrage against Iran this week, the Lebanese terror group has stayed out of the fray.

A network of powerful Iran-backed militias in Iraq has also remained mostly quiet, even though Israel allegedly used Iraq’s airspace, in part, to carry out the attacks.

Domestic political concerns, as well as tough losses suffered in nearly two years of regional conflicts and upheavals, appear to have led these Iranian allies to take a back seat in the latest round convulsing the region.

Hezbollah was formed with Iranian support in the early 1980s as a guerrilla force fighting against Israel’s occupation of southern Lebanon at the time.

The group helped push Israel out of Lebanon and built its arsenal over the ensuing decades, becoming a powerful regional force and the centerpiece of a cluster of Iranian-backed factions and governments known as the “Axis of Resistance.”

The allies also include Iraqi Shiite militias and Yemen’s Houthi rebels, as well as the Palestinian terror group Hamas.

At one point, Hezbollah was believed to have some 150,000 rockets and missiles, and the group’s former leader, Hassan Nasrallah, once boasted of having 100,000 fighters.

Seeking to aid its ally Hamas in the aftermath of the Gaza terrorist group’s October 7, 2023, attack on southern Israel and Israel’s subsequent offensive in Gaza, Hezbollah began launching rockets across the border.

That drew Israeli airstrikes and shelling, and the exchanges escalated into full-scale war in September 2024. Israel inflicted heavy damage on Hezbollah, killing Nasrallah and other top leaders and destroying much of its arsenal, before a US-negotiated ceasefire halted that conflict last November. Israel continues to hold five strategic points in southern Lebanon and to carry out near-daily airstrikes in what it says are ceasefire violations by Hezbollah.

For their part, the Iraqi militias occasionally struck bases housing US troops in Iraq and Syria, while Yemen’s Houthis fired at vessels in the Red Sea, a crucial global trade route, and also began targeting Israel with ballistic missiles.

Hezbollah and its leader Naim Qassem have condemned Israel’s attacks and offered condolences for the senior Iranian officers who were killed.

But Qassem did not suggest Hezbollah would take part in any retaliation against Israel.

Iraq’s Kataib Hezbollah militia — a separate group from Lebanon’s Hezbollah — released a statement saying it was “deeply regrettable” that Israel allegedly fired at Iran from Iraqi airspace, something that Baghdad complained to the UN Security Council over.

The Iraqi militia called on the Baghdad government to “urgently expel hostile forces from the country,” a reference to US troops who are in Iraq as part of the fight against the Islamic State group, but made no threat of force.

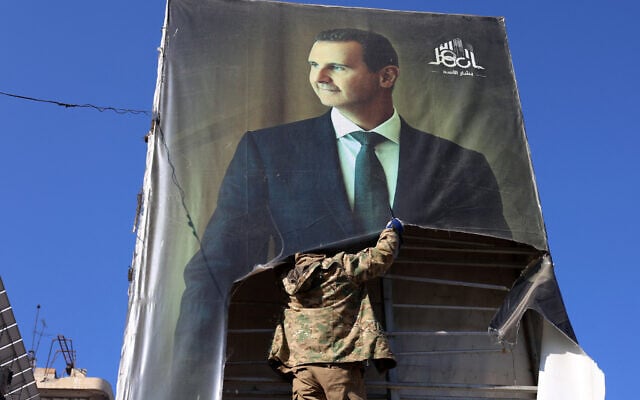

Hezbollah was greatly weakened by last year’s fighting and after losing a major supply route for Iranian weapons with the fall of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, a key ally, in a lightning rebel offensive in December.

The new government in Beirut, which has taken a harder stance with the wounded Hezbollah, also issued a warning to the group not to involve Lebanon in the fighting.

“Hezbollah has been degraded on the strategic level while cut off from supply chains in Syria,” said Andreas Krieg, a military analyst and associate professor at King’s College London.

Many Hezbollah members believe “they were sacrificed for Iran’s greater regional interests” since Hamas’s attack on Israel, and want to focus on “Lebanon-centric” interests rather than defending Iran, Krieg said.

Still, Qassim Qassir, a Lebanese analyst close to Hezbollah, said a role for the group in the Israel-Iran conflict should not be ruled out.

“This depends on political and field developments,” he said. “Anything is possible.”

Both the Houthis and the Iraqi militias “lack the strategic deep strike capability against Israel that Hezbollah once had,” Krieg said.

Renad Mansour, a senior research fellow at the Chatham House think tank in London, said Iraq’s Iran-allied militias have all along tried to avoid pulling their country into a major conflict.

Unlike Hezbollah, whose military wing has operated as a non-state actor in Lebanon — although its political wing is part of the government — the main Iraqi militias are members of a coalition of groups that are officially part of the state defense forces.

“Things in Iraq are good for them right now, they’re connected to the state — they’re benefitting politically, economically,” Mansour said. “And also they’ve seen what’s happened to Iran, to Hezbollah, and they’re concerned that Israel will turn on them as well.”

That leaves the Houthis as the likely “new hub in the Axis of Resistance,” Krieg said. But he said the group isn’t strong enough — and too geographically removed — to strategically harm Israel beyond the rebels’ sporadic missile attacks.

Krieg said the perception that the “axis” members were proxies fully controlled by Iran was always mistaken, but now the ties have loosened further.

“It is not really an axis anymore as (much as) a loose network where everyone largely is occupied with its own survival,” he said.