When nearly 6,000 terrorists from Hamas and other Gaza-based groups invaded southern Israel on October 7, 2023, they came not only to kill but to capture.

By nightfall, they had dragged 251 people back to the Gaza Strip: soldiers from their bases, mothers, toddlers and pensioners from their saferooms, even Thai farmhands.

“This large-scale kidnapping was a deliberate strategy,” said Boaz Ganor, executive director of the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism at Reichman University.

It was, in a sense, a proven strategy. Hostage-taking had for decades forced Israel to make major concessions, primarily the release of hardened terrorists.

Yahya Sinwar, the architect of October 7, learned this firsthand when, in 2011, he walked free from prison as one of 1,027 terrorists traded by Israel for captured soldier Gilad Shalit. In 1985, Sinwar’s mentor and Hamas’s founder, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, found his freedom the same way: Israel traded him and 1,150 other security prisoners for three captured IDF soldiers.

Jerusalem’s commitment to returning its captives from enemy hands — espoused by prime ministers, IDF veterans, hostage families and religious scholars — is a constant throughout the Jewish state’s history. But how Israel frees its hostages has evolved during the country’s 77 years, from straightforward POW exchanges to dramatic rescues to, more recently, lopsided swaps that set hundreds of terrorists free.

Now, for nearly two years, Israel has found itself in its largest and most complex hostage crisis yet. To secure the release of the vast majority of the hostages taken on October 7, Israel agreed to multiple deals that paused its campaign against Hamas and freed thousands of prisoners, including those with blood on their hands. Many believe Israel will have to do so again to get the remaining captives home.

Hamas’s leaders predicted, correctly, that Israel would pay the price, multiple analysts say. The Israeli public also seemed to take as a given that dozens of prisoners would be released for every hostage. In the two-month ceasefire that began in January, Israel released almost 2,000 terrorists and other prisoners in exchange for 30 living hostages and the bodies of eight more.

However, Israel didn’t always act this way. How did the Jewish state become accustomed to releasing masses of terrorists in exchange for a small number of hostages — even when doing so could place the lives of its citizens in peril?

Israel’s lopsided trades began in the 1950s on the battlefield, when thousands of Arab prisoners of war were swapped for small groups of Israeli soldiers. After the 1956 Sinai Campaign, Israel traded 5,500 Egyptians for four Israelis. Following the 1967 Six Day War, nearly 7,000 Arab POWs were released for 15 captured Israelis, and after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, some 8,000 Arabs were released for nearly 300 Israelis.

Though lopsided due to the stunning success of IDF ground operations, the swaps were relatively straightforward state-to-state arrangements governed by the conventions of international warfare.

“While Israel held the upper hand in terms of the sheer number of enemy soldiers it captured compared to the small number of Israeli prisoners held by the other side, this advantage was not reflected in negotiations,” wrote international relations expert Noa Lazimi in a 2023 Hebrew-language report on Israeli POW policy. In addition to the formal and legal nature of the exchanges, “this was largely due to Israel’s determination to bring conflicts to a close and accelerate the return of its captives — an imperative rooted in a formative value of the Jewish national ethos.”

‘Israel’s approach to hostages stands on two pillars: The Jewish value of redeeming captives, and every soldier’s belief that Israel will bring them home’

Colonel (Res.) Doron Hadar, commander of the IDF’s General Staff Negotiation Unit from 2007 until February 2024, acknowledged this value as a core principle in an interview with The Times of Israel: “Israel’s approach to hostages stands on two pillars: The Jewish value of redeeming captives, and every soldier’s belief that Israel will bring them home,” he said.

The early prisoner swaps reflected this ethos and helped cement in the public mind a perceived “equation of sorts,” Hadar said, namely that the return of an Israeli soldier was worth the release of many enemy prisoners.

Israel’s tactics anticipated the lopsided ratio: Former general and future prime minister Ariel Sharon acknowledged in 2000 that during the 1950s — after terror attacks at home and through reprisal raids in Arab countries — Israel built a “prisoner bank,” holding enemy detainees as bargaining chips for future abductions.

In 1954, the policy led some Israeli leaders to consider drastic steps. After a botched IDF mission near the Golan Heights left five Israeli soldiers in Syrian hands, defense minister Pinchas Lavon green-lighted seizing a Syrian military aircraft as a bargaining chip. IDF chief of staff Moshe Dayan went further, ordering the air force to intercept a Damascus-Cairo civilian flight and trade its passengers for the captives. But prime minister Moshe Sharett intervened to veto the plan, ruling that civilians were off-limits.

Back in Syria, one of the captives — 19-year-old Uri Ilan — was falsely told his comrades had been executed. Determined not to give up military secrets under torture, he hanged himself, hiding a Hebrew note in his uniform reading, “Lo Bagadti” (I did not betray). Two years after their abduction, Israel ultimately handed over 41 Syrian prisoners, most taken in prior IDF raids, for the four surviving soldiers and the body of Ilan, whose suicide note made him a national hero.

An early precedent had been set, cemented in the bond between state and soldier: No captive is abandoned, dead or alive, even when the price is steep.

Israel’s determination to bring back all its captives did not go unnoticed by its enemies.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the country faced a wave of Palestinian terrorism characterized by both mass-casualty attacks and barricaded hostage situations, in which terrorists seized control of confined civilian spaces such as airplanes, schools, buses and hotels, and held those inside as bargaining chips.

Armed Palestinian secular nationalist groups, including Fatah and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), increasingly turned to such tactics, hoping to belittle Israel and force concessions.

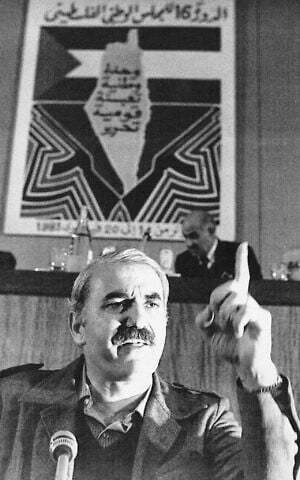

PFLP co-founder George Habash, a Marxist, believed that dramatic, high-profile acts of terror would bring international attention to the Palestinian cause.

In mid-1968, when Israel’s adversaries were still reeling from the Six Day War, the PFLP managed the only successful hijacking of an El Al plane in history, diverting a carrier to Algeria and holding its crew plus the male Jewish passengers as hostages. Israel ultimately freed 16 convicted terrorists in exchange for the passengers, but waited three weeks before doing so, disguising the concession as a goodwill gesture to Algeria.

In an interview with Israel Hayom last year, 82-year-old Avner Slapak — one of the El Al hijacking survivors — discussed both the hostages’ faith in their government’s determination to bring them home, and their aversion to rewarding terror: “We were 12 men who were taken captive, and only one of us spoke about the possibility of a prisoner exchange. All the others, including me, agreed that the bastards who had abducted us did not deserve the prize of having even a single murderer released in return for us. All the time we said, ‘The government of Israel will ensure that we are released.’”

‘The bastards who had abducted us did not deserve the prize of having even a single murderer released in return for us’

Throughout the 1970s, Israel adopted a stricter stance against negotiating with terrorists, led primarily by then-prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, who was in office from 1974 to 1977. This hardline policy, later known as the “Rabin Doctrine,” emphasized rescue operations over negotiations, even at the risk of losing Israeli lives.

In early 1974, a last-minute decision by prime minister Golda Meir to storm a school in Ma’alot, where Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine terrorists had taken over 100 students hostage, saved many children but left a quarter of the young captives dead. The tragedy led to the creation of the Yamam, Israel’s elite counterterrorism unit, among other reforms.

The following year, eight hostages and three soldiers died during a rescue operation at the Savoy Hotel in Tel Aviv. Seven of the eight terrorists were killed, while the remaining one was captured and later freed in the same 1985 deal that released Yassin. Three years later, 38 out of 71 captive civilians, 13 of them children, were killed by a group of 11 Fatah terrorists during the Coastal Road bus massacre, before troops eliminated most of the perpetrators.

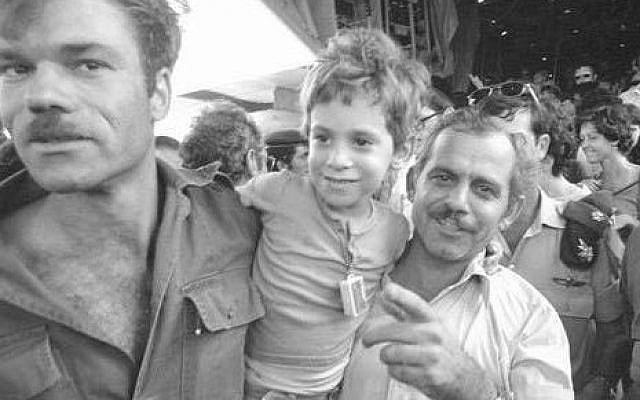

The doctrine’s defining moment came in the 1976 Entebbe operation. When Palestinian and German terrorists hijacked an Air France flight and diverted it to Uganda, holding its Jewish and Israeli passengers at gunpoint, Rabin wavered between negotiation and force. Ultimately, he sent elite Sayeret Matkal commandos over 3,500 kilometers (2,500 miles) to Entebbe Airport, where they freed more than 100 hostages.

Though the raid cost the lives of three captives and Yoni Netanyahu, the mission commander and elder brother of the current premier, the operation was celebrated. Its success cemented Israel’s preference for armed rescue over bargaining whenever a military option exists.

In response to the Rabin Doctrine, Palestinian terrorists initially reduced their demands in hostage crises. The lighter demands, rather than being a concession, aimed to disincentivize military rescues, and to heighten Israeli public backlash if the rescues failed.

When Israel still refused to yield, terrorists shifted their tactics to ensure that the IDF could not come to the rescue.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, Palestinian terror groups began spiriting Israeli hostages — mostly soldiers — deep into enemy territory, making successful commando raids extremely risky, if not impossible.

“Without the option of implementing the Rabin Doctrine’s military rescue option, Israel found itself negotiating for the release of hostages,” Ganor explained. “Israeli decision-makers found themselves on a slippery slope.”

A turning point came in 1978. During Operation Litani, Israeli reservist Avraham Amram was captured by the PFLP and held in Lebanon for 340 days. Tortured and suicidal in captivity, Amram was eventually freed through a Red Cross-mediated exchange for 76 Palestinian security prisoners. The deal was approved as Israel pursued peace talks with Egypt.

From that point on, Israel routinely released dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of prisoners in exchange for small numbers of Israeli captives, and sometimes for their remains. Groups such as Fatah, the PFLP, the DFLP, Hamas and Hezbollah all exploited the trend.

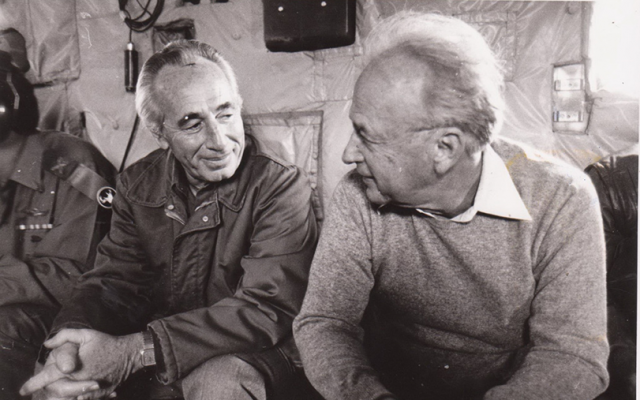

In 1982, during the First Lebanon War, eight Israeli soldiers were captured from their post by terrorists. Fatah held six, and two were handed to the PFLP General Command, headed by Ahmed Jibril. A year later, prime minister Yitzhak Shamir’s government released over 4,700 Palestinian and Lebanese prisoners for the six held by Fatah.

A sense of urgency seemed to grip Israeli decision-makers: “We paid a high price for the six,” Shamir told reporters at the time, “but we were faced with the fact that their lives were in peril, and that at any moment the worst could happen.”

The price of Israeli captives remained high in 1985 with the Jibril Agreement, when Israel traded 1,150 terrorists — including 380 serving life sentences, such as Yassin and a Japanese terrorist who participated in a Tel Aviv attack that killed 26 people — for the remaining two soldiers held by the PFLP–GC, along with an additional captive taken during the Lebanon War.

The decision aligned with Rabin’s policy of trading prisoners for hostages when rescue wasn’t possible. But because it set arch-terrorists free, it created a new reality and, according to Ganor, set a dangerous precedent.

Then-premier Shimon Peres acknowledged that the price was dear, but emotion seemed to tip the scales. He told the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee at the time that while “the decision to exchange terrorists was one of the most difficult…when meeting with the families, a lot of criteria were given a new dimension. It was so hard to see them suffer, so difficult.”

In another sign of things to come, public pressure may have also played a role. The families of the hostages had been rallying the public to help retrieve their children, including Miriam Grof, mother of captured soldier Yoske Grof, who launched a relentless campaign to shake hardened senior officials.

“It is difficult to explain, but only someone who met that woman could understand how she filled everyone with a deep, blood-boiling, paralyzing sense of shame,” Eitan Haber, a well-known Israeli military correspondent and former senior aide to Rabin, told the New York Times in 2011. “We are speaking about three very tough men [Rabin, Peres, and Shamir] who had no problems saying no, but simply could not stand up to Mrs. Grof… Her aggressiveness was not of this world. She broke them all down.”

For her part, Grof told POW support group Erim Balaila, Hebrew for “awake at night,” in 2007: “I didn’t want and I still don’t want to be a hero. All I wanted was one thing: to return my son safely home.”

‘I didn’t want and I still don’t want to be a hero. All I wanted was one thing: to return my son safely home’

Some decision-makers later regretted their support for the deal. Former defense minister Moshe Arens, who was a minister without portfolio at the time, wrote in his 2018 memoir: “I voted for the [Jibril] agreement — and regret it to this day… The immediate sense of relief… always seemed to take precedence over the potential long-term danger.”

Perhaps bruised by the fallout, Israel refused to meet demands for captured pilot Ron Arad, taken in 1986 by the Lebanese Amal terror group and later held by Hezbollah. Arad was never returned and is presumed dead. His unresolved case became a national scar invoked in hostage crises since, including today’s.

Udi Goren, whose cousin, Tal Haimi, was murdered and abducted by Hamas on October 7, told The Times of Israel, “If until October 7 we had just one Ron Arad, who was already a deep wound in Israeli society,” then if the government fails to return all the Gaza hostages, “we are going to have many Ron Arads.”

Despite the Arad exception, the trend of lopsided prisoner exchanges persisted. In January 2004, Sharon released over 430 Palestinian and Lebanese prisoners in exchange for businessman Elhanan Tannenbaum — who had been kidnapped by Hezbollah after being lured into a drug deal in Dubai — as well as the bodies of three Israeli soldiers.

In the months before the Shalit deal was completed in 2011, the Tannenbaum deal was raised in the debate over the release of terrorists in exchange for hostages. Former Mossad chief Meir Dagan criticized proposals to swap a large number of prisoners for Shalit, claiming that “Two hundred thirty-one Israelis were slaughtered by those freed in the Tannenbaum exchange.” Netanyahu, presiding over the crisis during his second term as premier in 2011, publicly stated, “Those released in the Tannenbaum deal murdered 27 Israelis since 2004.”

Against the backdrop of the Shalit debate, there were attempts to formally curtail the pattern of massive prisoner swaps. In 2008, Israel convened the Shamgar Commission, headed by former chief justice Meir Shamgar, to codify clear hostage negotiation guidelines. Its classified recommendations reportedly urged equal exchanges, minimal contact between the political echelon and the families of hostages to minimize emotional appeal, and worsening conditions for terrorists in Israeli prisons to increase leverage. The report was submitted to the Defense Ministry after Shalit’s release, but was never adopted.

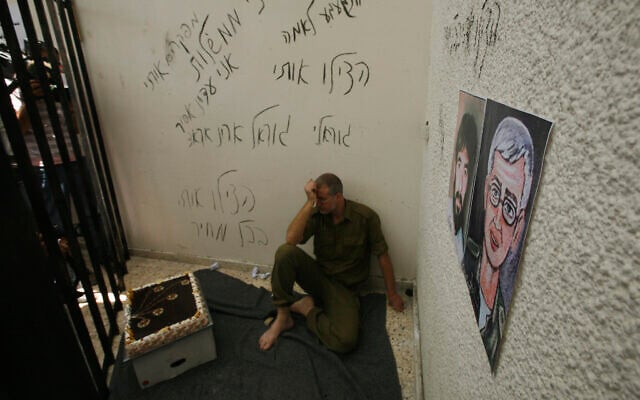

Following years of public campaigning by Shalit’s family and crowds of supporters, the 25-year-old soldier was freed in exchange for 1,027 terrorists, including Sinwar and over 300 others serving life terms

Despite the policy debate, hostage-prisoner exchanges reached an unprecedentedly uneven ratio. Five years after Hamas and other Gaza-based groups snuck across the border and dragged Shalit from his tank into the Gaza Strip, Netanyahu approved the most dramatic swap in Israeli history. Following years of public campaigning by Shalit’s family and crowds of supporters, the 25-year-old soldier was freed in exchange for 1,027 terrorists, including Sinwar and over 300 others serving life terms. About half the prisoners were collectively responsible for terrorist attacks in which 569 Israelis were murdered.

Ganor, who advised Netanyahu on his 2001 book “Fighting Terrorism,” acknowledged that many saw the premier’s motivations as primarily political. At the same time, the public sympathized with the difficulty of decision-makers in hostage crises: “If Bibi simply had the job of being a counterterrorism expert, like me, it’s easy to take a very clear and tough position on what should not be done — and probably rightly so. But when you carry the weight of real hostages on your shoulders, your perspective changes.”

The lengths Israel will go to free its hostages and the motivation of Hamas to empty Israel’s jail cells continue to play off one another. One of the terror group’s main goals on October 7 “was to capture soldiers and civilians to get back prisoners,” Hadar explained, noting that before the attack, “one of the top issues on the Gazan public’s mind was the thousands of security prisoners held by Israel.”

After October 7, calls to revive the spirit of the Shamgar Commission for hostage policy reform resurfaced for some activists. Families bereaved of terror victims and the advocacy group Almagor petitioned the High Court to bar any new mega-swap, with one family member claiming that “the Shalit deal gave birth to October 7.” The justices declined to intervene.

Hamas’s goal of releasing prisoners has already paid off. Yoram Schweitzer, an analyst at the Institute for National Security Studies and former IDF intelligence officer who advised the Shalit talks, pointed out: “We’ve already released around 2,300 prisoners during the war in the past two hostage deals, some 280 of them who were serving lifetime sentences.” He added that Hamas “still has a veteran list of lifers it very much wants to set free.”

Despite resistance from defense officials, Netanyahu defended the Shalit deal at the time of its approval, citing the national memory of Ron Arad and the lifelong anguish of the lost pilot’s mother.

“I thought of Gilad and the five years that he spent rotting away in a Hamas cell,” he said. “I did not want his fate to be that of Ron Arad… I remembered the noble Batya Arad… her concern for her son Ron, right up until her passing… At such moments, a leader finds himself alone and must make a decision. I considered — and I decided.”

Now, with 50 hostages still in Gaza — including 20 believed to be alive and the remains of a soldier taken in 2014 — Netanyahu must decide again, but with far more than a single captured soldier on the line.

Following the unprecedented trauma of October 7 and its aftermath, surveys show the dominant public demand is to bring everyone home, not only by freeing more terrorists but by potentially stopping the war without a decisive defeat of Hamas.

The terror group released 105 civilians as part of a truce deal and four others outside any official framework in 2023, another 38 captives during a 42-day ceasefire that ended in March, and a dual US-Israeli hostage in May. Israel has also rescued eight captives in military raids and recovered 49 bodies. Since March, hostage-ceasefire talks have largely been at a standstill, mainly over the issue of bringing a permanent end to the war, though the sides have reported new momentum in recent weeks as US President Donald Trump has pushed for an end to the fighting.

For many, the established practice of returning hostages even at great cost must prevail, especially in light of the unprecedented trauma of October 7.

‘There’s no doubt Israel needs to reform its hostage policy, but after October 7 is not the time to shift gears’

“There’s no doubt Israel needs to reform its hostage policy,” Ganor said, “but after October 7, in this singular case, where so large and so varied a group of hostages was taken, it is not the time to shift gears.”

Schweitzer, who spent years interviewing both current Palestinian security prisoners and Shalit-deal releases, said he “knows these prisoners well” and nonetheless believes that rejecting a life-saving swap over the issue of recidivism “is the antithesis of the Israeli concept of mutual responsibility.” Israeli society must “take a risk to save someone whose death or suffering is certain,” while security services can take care of future threats, he said.

After 27 years of experience in hostage negotiations, Hadar agreed: “We bring our hostages home — even if it means more work later.”

Goren, a member of the Hostages and Missing Families Forum, representing the majority of the hostages’ families, warned that failing to return all the captives would equal “dismantling the IDF’s value system, the Zionist ethos that ‘no one is left behind.’ It’s already happening now.”

In contrast, Maj. Gen. (res.) Gershon Hacohen, a former IDF general who spent over 42 years in uniform and oversaw the IDF pullout from Gaza in 2005, does not consider failure to return all the hostages to be detrimental to Israel’s morale.

Hacohen cautioned against absolute slogans like “Bring Them Home Now.”

“Strategy is all about flexibility,” he said. “Yes, war involves terrible prices, but we are a strong nation, and we can absorb them. We must reassess daily: defeat Hamas and save the hostages, but not at any cost. War demands a broader perspective.”

The hostages’ families in the Tikvah Forum, led by Tzvika Mor, father of hostage Eitan Mor, push Israel to exercise force over demonstrating flexibility, and call for a relentless IDF campaign until Hamas capitulates to a single comprehensive deal.

“We demand political, military, and humanitarian pressure on Hamas to bring everyone home — together,” Mor told The Times of Israel. Tikvah Forum spokesman Benaya Cherlow praised hostages’ relatives willing to “put national security above their own grief” by resisting an immediate ceasefire or demands to end the war.

Every path has its costs. Refusing to meet Hamas’s demands leaves behind 50 hostages, including the 20 living captives in mortal danger, while releasing terrorists and failing to crush Hamas may put many future Israelis in harm’s way.

To the advocates of the competing policies, it’s not only the lives of Israelis that hang in the balance. It is also a matter of what kind of Israel emerges when the last hostage finally comes home — or doesn’t.