More than 600 days after the October 7, 2023, Hamas massacre, Israeli soldiers are once again ramping up an operation that, the country’s leaders say, is the key to finally winning the war.

In the meantime, hostages remain in Gaza, it is still unclear what exactly will lead to Hamas’s defeat, and Israel’s standing in the world continues to slip.

We don’t know what will happen next — whether more hostages will be released, when the war will come to an end, what the promised total victory will constitute, and what Israel’s relationships abroad will look like in the aftermath.

Still, there are core insights into the war and its wider context that can help understand where the campaign stands now, and where it should head in the future.

Before Hamas’s October 7, 2023, invasion and slaughter in southern Israel, the Iran-backed terror group Hezbollah in Lebanon was far more dangerous and capable than Hamas, and Israel behaved accordingly over the last decade. A state of mutual deterrence persisted across Israel’s northern border, as Israel drew up war plans and Hezbollah did the same, expanding its capabilities as the years went by.

Were conflict to break out with Hezbollah, the IDF predicted, 2,000 rockets a day would rain down on Israel, taking a ghastly toll while paralyzing the country.

The campaign played out very differently. Hezbollah entered the war on October 8, 2023, and months of back-and-forth rocket attacks and airstrikes ensued. Then, after deciding to escalate in the late summer of 2024, Israel carried out a series of high-profile operations, detonating booby-trapped beepers and assassinating the terror group’s Hassan Nasrallah and the leadership of the elite Radwan force.

Demoralized and overwhelmed, Hezbollah couldn’t do anything to stop Israel’s limited ground invasion, and accepted a humiliating ceasefire. Israel still has troops in Lebanon and carries out strikes on Hezbollah targets, with no response from the once-feared organization.

A new president representing the anti-Hezbollah faction is now in power in Beirut, with firm US and French backing, and the Lebanese Army has reportedly dismantled most of Hezbollah’s posts and weapons stockpiles in the country’s south, with the help of Israeli intelligence.

And as a nice bonus, shortly after Hezbollah threw in the towel, the Bashar Assad regime collapsed in Syria, replaced by a weak new government that has no interest in conflict with Israel.

At the tactical level, the IDF has performed impressively in Gaza. It can reach anywhere it wants in the Strip, easily rolled up Hamas defenses early in the war, and has adapted to the complex challenges presented on a battlefield prepared by Hamas for 17 years.

It has also killed all of Hamas’s top leadership in Gaza, and the vast majority of its battlefield commanders.

Yet Hamas fights on. And it remains the only force in the Strip able to assert control over the population: Nearly 20 months after it perpetrated the worst slaughter of Jews since the Holocaust, Hamas is still not defeated.

Israel has not been clear about how exactly tactical success leads to the strategic goal of defeating Hamas. Is it through taking territory? Israel seemed to think so early in the war, boasting about the areas it had captured — Gaza City, the Netzarim Corridor, the Philadelphi Corridor, the Rafah Border Crossing.

But there is no one particular piece of territory that Hamas needs to hold onto in order to outlast Israel. Almost anywhere will do.

Perhaps the killing of Hamas fighters is the key to victory?

“Another battalion dismantled, another commander killed, another infrastructure destroyed, this is the way to eventually pressure for the release of the hostages,” said then-IDF chief of staff Herzi Halevi in April 2024.

Israel has certainly taken tens of thousands of Hamas gunmen off the battlefield, severely eroding Hamas’s effectiveness. Yet there are still thousands left, more than enough to reassert control and start rebuilding if Israel withdraws.

Another theory of victory sees Hamas’s leadership as its center of gravity. The IDF has killed Yahya and Mohammed Sinwar, Mohamed Deif, Marwan Issa, and almost all brigade and battalion commanders. But the group has not given up or splintered into rival factions.

Israel hasn’t managed to get the population to overthrow Hamas either. There have been occasional protests, which are either put down by Hamas or dissipate. Israel plays up these demonstrations, but it hasn’t provide an incentive for Gazans to turn against Hamas with the promise of a rapid improvement in conditions. It has tried to get the population to turn against Hamas by limiting humanitarian aid — but that has failed, and eroded support for the war among Israel’s allies.

It seems to be quietly arming Gazan criminal clans as well.

Now Israel is pursuing the idea that offering humanitarian aid is the key to victory — provide it, but keep it out of Hamas hands, and the terrorists lose their funding and control of the population. The new Gaza Humanitarian Fund is designed to test that proposition. Its rollout has been bloody and chaotic, but Hamas’s opposition to it is a good sign.

It will have to be expanded, made safer, and supported by other countries and aid organizations in order to permanently weaken Hamas’s hold over Gazans.

For a number of reasons, but primarily coalition politics, the government refuses to elucidate a clear vision of what Gaza would look like after Israel’s “total victory.”

Hamas is not immune to military defeat, like so many observers argue. That defeat becomes much harder to achieve, however, without a plan for alternative governance. It would give more purpose to military operations, and would impose an overarching logic on IDF actions.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is treating Trump’s “Gaz-a-Lago” idea to resettle Palestinians as his vision for the future of Gaza, which is a convenient way to dodge having to actually come up with one.

A postwar plan would also increase international support for Israel’s military campaign. Legitimacy to continue operations that impose harsh costs on Gaza’s population is easier to maintain when allies believe that the suffering is leading to a better future. Without that vision, it’s hard for even Israel’s closest friends to understand why they should support more death and hunger.

On May 5, a senior Israeli defense official said the IDF would launch its major offensive against Hamas in the Gaza Strip, dubbed “Gideon’s Chariots,” if no hostage deal was reached with the terror group by the end of US President Donald Trump’s visit to the region the next week.

Trump came and went. No deal was reached.

The “Gideon’s Chariots” objective, according to defense officials, is nothing less than the defeat of Hamas in Gaza and the release of all hostages.

According to one official, “a central component of the plan is the extensive evacuation of the entire Gazan population from combat zones, including from northern Gaza, to areas in southern Gaza, while creating separation between them and Hamas terrorists, in order to allow the IDF operational freedom of action.”

“Unlike in the past, the IDF will remain in every area that is conquered, to prevent the return of terror, and will handle every cleared area according to the Rafah model, where all threats were leveled and it became part of the security zone,” he said.

Though all the IDF’s active ground brigades are in Gaza, the operation is not a rapid, aggressive one.

Instead, it boasts incremental gains. Military officials say that the IDF is aiming to take 75% of the Strip within two months, and that the army is shifting its focus away from trying to eliminate as many terrorists as possible to instead capture territory and destroy Hamas’s infrastructure.

A map shared Tuesday by the IDF showed five divisions moving further into Gaza.

If, for whatever reason — external pressure, troop shortages — Israeli forces end up leaving these areas, then the much-vaunted intensified campaign will essentially be a replay of what the IDF has been doing at the height of its military operations over the past year and a half.

The difference is that the IDF says it intends to hold onto the captured territory until Hamas gives in. Could that make the difference? Potentially. But if Hamas’s goal is to simply survive, it’s not clear why it wouldn’t hunker down along with the rest of the Gazan population until something changes — US pressure on Israel or another temporary ceasefire deal.

Even as the IDF slowly retakes territory in Gaza, it’s clear that Israel is still focused primarily for now on pushing Hamas to accept a hostage deal, not on definitively defeating Hamas militarily.

Since October 7, Israel has operated as if it has no time limits in its Gaza war.

Its initial ground campaign was designed to be slow and deliberate, not to bring the war to a rapid decision as Israel’s classic military doctrine holds.

With inadequate intelligence on Hamas and the Gaza Strip, and a lack of confidence in its ability to dust off its ground maneuver capabilities, the IDF moved slowly in its major ground offensive in late 2023 and early 2024. It used massive firepower to protect its forces, which advanced only as fast as its bulldozers could clear routes.

And Israel didn’t attack in multiple sectors simultaneously, as military doctrine would anticipate. It started with Gaza City, then shifted to Khan Younis in December, and — faced with threats from the US Biden administration — only began its Rafah operation in May 2024.

A long war only raises the costs for Israel: more strain on reservists, more harm to the economy, and more erosion of Israel’s diplomatic standing.

There were some understandable reasons for a slower pace: Israel doesn’t want to risk striking areas where hostages may be held, and two hostage deals brought temporary ceasefires.

Nevertheless, no rush has been seen to win the war and move on to building a new future in Gaza and the region.

That is a risky approach. The Trump administration has given Netanyahu plenty of room to do what he wants with Gaza, but the longer it remains a problem with no obvious movement toward a resolution the greater the risk of Trump getting sick of backing the campaign.

Europe and pro-Western Arab states are ramping up their efforts to end the war, and are sure to bring this goal up in their meetings with Trump. Eventually, it might work.

Israel’s international legitimacy in the war was always going to start seeping away, from the moment the IDF’s guns opened fire.

In the aftermath of the October 7 Hamas attack, Israel seemed to think that, given the scale of the atrocities, no one was going to get in the way of its military campaign. It did not prioritize limiting civilian casualties, and has played politics with the provision of humanitarian aid throughout the war.

Both of these mistakes have increasingly pushed allies to call for an end to the war, without conditioning it on the return of hostages or the defeat of Hamas.

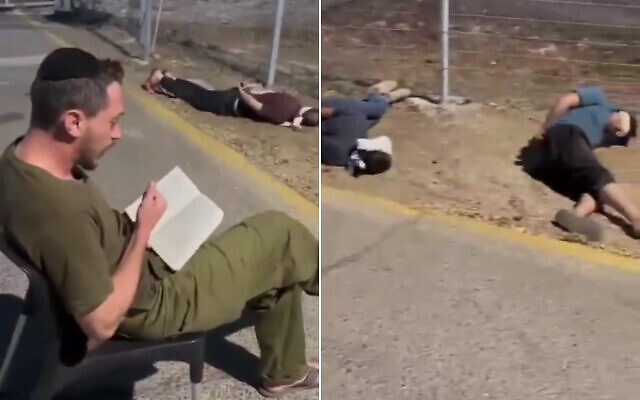

The IDF brass didn’t help either. Active and reserve soldiers began uploading videos from the battlefield to their social media accounts for the world to see. Some of it was juvenile tomfoolery; much was inappropriate partisan opinion; and there was even footage depicting war crimes.

Instead of swiftly cracking down on the perpetrators, whose videos were collected by anti-Israel groups and by international courts, the IDF failed to get a handle on the trend. Strategic and irreversible damage was done to the IDF’s image, and to the war effort.

Government ministers and MKs have caused similar harm in front of microphones.

Agriculture Minister Avi Dichter said the war was “Gaza’s Nakba.”

“Erase Gaza from the face of the earth,” said Likud lawmaker Galit Distel-Atbaryan. “Let the Gazan monsters rush to the southern border and flee into Egypt, or die. And let them die badly. Gaza should be wiped off the map.”

Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich predicted that the Strip would be “totally destroyed.”

Such statements from ministers and lawmakers are a pillar of the International Court of Justice’s genocide case against Israel.

Netanyahu offered tepid suggestions to his government to take more care with their utterances, but has not cracked the whip on ministers who harm Israel’s campaign for their own political gain.

It should be noted that the countries criticizing Israel have adopted a hypocritical stance since the beginning of the war. They purport to care deeply for the lives of Gazans, but didn’t demand escape routes for civilians, as they did for Syrians and Ukrainians. They point to fears of Israel not letting Palestinians return to Gaza — but shouldn’t it be the personal choice of individual Gazans whether to protect their physical well-being or risk the dangers of war in order to hold onto Palestinian land?

Israel believes time is on its side. Hamas reads the situation differently. It is convinced that eventually, domestic or international pressure will force Israel to end the war, which would mean victory for Hamas.

Its entire goal at this stage is to survive the war with a core of fighters and commanders in Gaza.

If it manages that, it will remain the most powerful force in the Strip. At some point, it will find the opportunity to slowly rearm, and possibly reassert full control.

This, of course, is the major sticking point in talks with Hamas. The terror organization insists that any further release guarantee an end to the war. Israel refuses to grant Hamas victory, and a deal remains out of reach.

Though it faces international opprobrium and angry protests over the issue — including over its refusal to accept a deal that would bring home all the hostages in exchange for an end to the war — the Netanyahu government has managed to free the majority of hostages. Out of 251 taken on October 7, 148 have made it home alive, mostly through deals with Hamas, but several through military operations and sporadic releases by Hamas.

Israel has brought home another 51 bodies.

Finding a way to free 199 hostages from a ruthless terrorist organization that revels in the killing of Jews is no small feat. Though the government may not be formally prioritizing the freeing of the hostages over the defeat of Hamas, to the ire of much of the country, it certainly has harmed its own military campaign in order to avoid endangering hostages and to conduct hostage release deals.

It continues to delay full implementation of the much-ballyhooed ground campaign in order to keep the door open for another hostage release by Hamas in exchange for an extended ceasefire.

Families of hostages and their supporters call clearly and loudly for a deal that brings all the hostages home, at the price of ending the war if necessary.

They make a number of arguments.

One is that once Israel brings all of the hostages home, it can restart the war the minute Hamas violates the terms of the ceasefire , which it is sure to do.

That is simply not realistic. Hamas is brutal, bloodthirsty, and ruthless, but isn’t stupid. Before giving up the hostages, its most valuable asset, it would make sure it had every rock-solid guarantee in place that Israel couldn’t just resume the fight.

The most reliable guarantee is a UN Security Council resolution imposing a range of harsh sanctions on Israel if it goes back to war. Hamas can’t initiate such a resolution. But if that’s what stands between an end to the war and more bloodshed in Gaza, it is absolutely conceivable that the US, Britain, and France would support it.

To put it starkly, there is no way to get all the hostages home if Hamas believes there is any chance Israel will go back into Gaza.

A second, moral argument is that there is an ethical imperative to bring back the hostages while they are still alive, and this trumps the goal of destroying Hamas.

This approach has guided Israeli decision-making in its repeated hostage release deals over the years. It has time and again brought home a small number of hostages while releasing hardened terrorists, some of whom have gotten right back to work killing Israelis.

According to former Mossad chief Meir Dagan, 231 Israelis were killed by the terrorists released in the 2004 deal that freed Elhanan Tannenbaum and brought home the bodies of 3 IDF soldiers.

Famously, Yahya Sinwar — the Hamas leader who masterminded October 7 — was one of the 1,027 security prisoners released in the 2011 deal that freed one IDF soldier, Gilad Shalit.

There is a difference this time, however. The previous deals were pure swaps, and did not force Israel to prematurely end a military campaign.

This time, it would.

The decision, then, should be laid out clearly. It’s a choice between winning a war against a terrorist organization, and saving the lives of about 20 people — the number of hostages assumed to be alive in Gaza. Or, as the Hostage and Missing Families Forum says: “Save the hostages. End the war.”

Choosing the lives of the hostages over victory would not be unprecedented, but would be extremely rare in the history of war. Russia agreed to halt military operations in Chechnya and engage in talks after Chechen terrorists took almost 2,000 civilians hostage in Budyonnovsk in 1995.

In 1360, after King John II was captured by the English, France agreed to cede significant territories to secure the release of its monarch in the Treaty of Brétigny.

But the few obscure historical examples fly in the face of the logic of war. If the goal was to avoid the deaths of a small number of citizens, no country would go to war at all, as wars are fought with the knowledge that soldiers will be sacrificed for political aims.

If Israel’s war to defeat Hamas isn’t worth the lives of 20 citizens, then why would it be worth the lives of the 425 soldiers that have fallen in the 20 months of fighting?

One could argue that, given the failure of the security services to protect the country on October 7, this case is unique. Civilians were snatched from their homes, off-duty and conscript soldiers found themselves in sudden and desperate fights, and the military for hours failed to take actions that could have prevented many of the hostages from being taken. There is a moral obligation owed to these Israelis, the argument goes, and if it is not fulfilled the covenant between the state, the military and the public will be irrevocably shattered.

The Hostages and Missing Families Forum, and the hostage movement as a whole, has demanded that Israel’s absolute priority be bringing every hostage home. #Untilthelasthostage, says the slogan printed on their posters.

The straightforward goal of bringing every hostage home, one would hope, is accepted by all without question.

The call in this case is more specific, however. It is an insistence that the government make whatever concessions are necessary to get every last captive, living and dead, back from Gaza.

It’s a morally reasonable position.

It was just oddly absent for the decade before October 7, during which the bodies of two IDF soldiers and two living civilians were held by Hamas in Gaza. By the standards established since the Hamas invasion, there should have been mass protests for years demanding the government free prisoners and grant other concessions to Hamas in order to get every last hostage home.

When the family of Hadar Goldin led a march in 2022 to mark eight years since his body was taken by Hamas, while calling for the release of the body of Oron Shaul and of living civilians Avera Mengistu and Hisham al-Sayed, they were joined by only hundreds of Israelis, not tens of thousands.

Successive Netanyahu governments, along with the Naftali Bennett-Yair Lapid government, did not treat the issue as a priority, and the public followed suit.

The current crisis has also seen captives slain in Gaza being referred to as hostages. The reasoning is clear — to stress the value of bringing bodies home for proper burial in Israel, even if it means paying a painful price.

But that’s not the terminology used before October 7. Hostages referred to the living. News outlets, including this one, spoke of Hamas holding “two hostages” until October 7, in addition to the bodies of the two IDF soldiers.

Now Israeli leaders and journalists speak about 56 hostages, of whom 20 are still living.

It may be that the October 7 attacks were so unprecedented that it has changed the way Israeli think about hostages, living or dead.

There is also an undeniably political aspect to the protests. Some percentage of the demonstrators — it is impossible to say how large — is firmly in favor of a full hostage deal that ends the war because it has been anti-Netanyahu since long before the war.

At the same time, the language being used risks obscuring a difficult conversation that must be had: How much should Israel give up for the return of bodies? Calling them hostages indicates that the price should be nearly identical to living hostages. That is the choice Israel made in the Tannenbaum deal.

Is it what Israel should be doing now? That question has pressing real-world consequences, and obscuring the urgent need for an answer is ultimately not in the country’s best interest.

Israel is facing a barbaric enemy, which had the better part of two decades to prepare for a war in which it put its own people in harm’s way by design. Israel’s war aims are just and reasonable.

But 20 months after October 7, Israel has achieved none of its goals. It has performed countless impressive feats on the battlefield and even on the diplomatic front. Without the right leader and strategy, however, those successes don’t add up to victory.

Victory is still attainable. The longer Israel continues to avoid being decisive, the more likely it is that victory will slip out of reach.