Researchers at Tel Aviv University and Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center say they can measure memory by tracking subjects’ eye movements when watching videos. The new protocol opens the door for testing nonverbal individuals — and even animals.

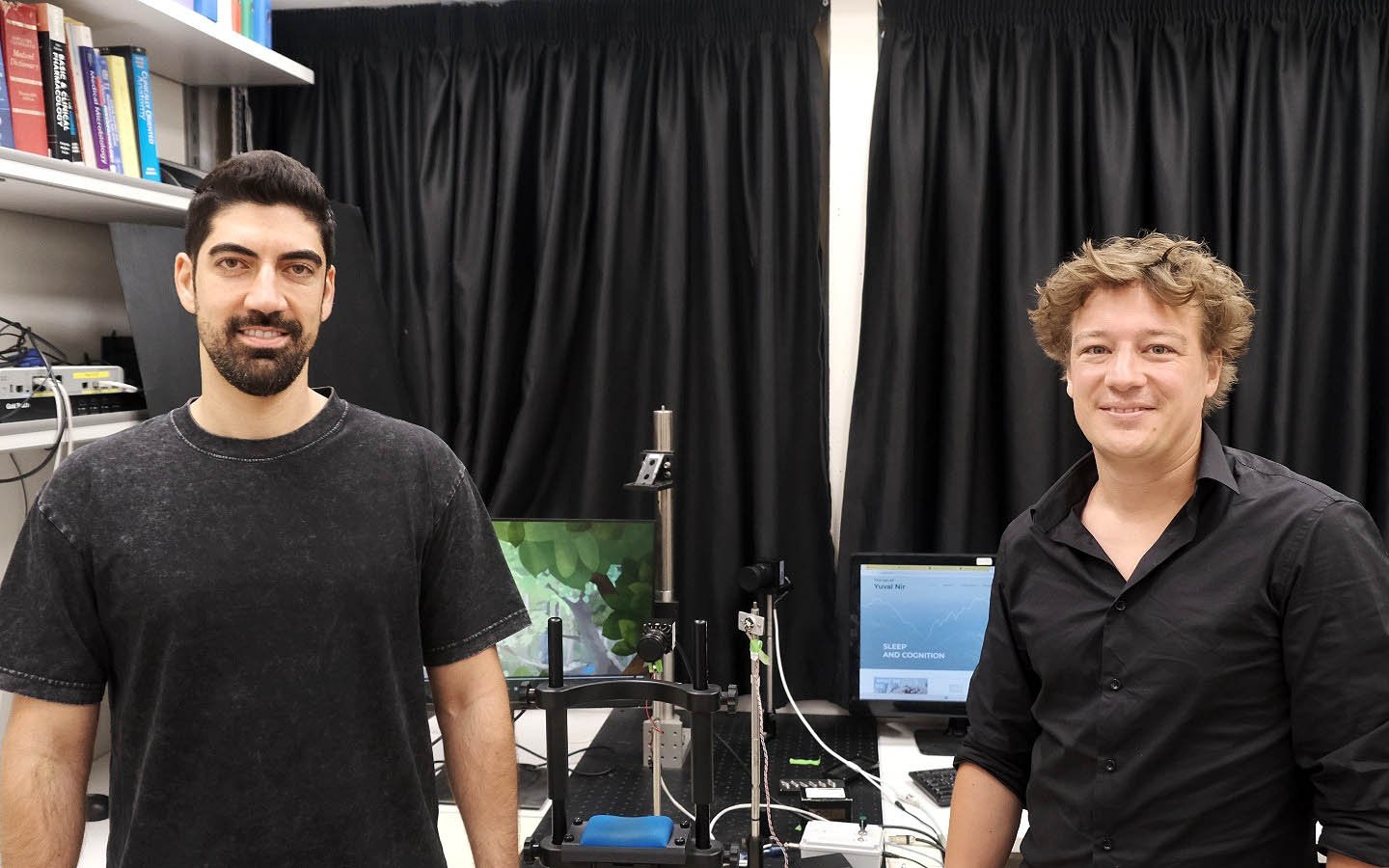

“Memory is usually tested through direct questioning, with subjects verbally reporting whether they remember a certain event,” said lead scientist Dr. Flavio Jean Schmidig, currently completing his postdoctoral research in Prof. Yuval Nir’s lab in Tel Aviv’s Sagol School of Neuroscience.

“For example, a subject might be shown a picture and asked if they remember having seen it before,” he said, speaking to The Times of Israel by teleconference. “However, this type of testing cannot be performed on animals, infants, patients with advanced Alzheimer’s, or people with head injuries who cannot speak. The method excludes a lot of groups.”

Schmidig said that the groundbreaking study tested “memory in a more natural way,” without the intrusions of questioning subjects or their need to respond.

The study was conducted in collaboration with Dr. Daniel Yamin, Dr. Omer Sharon, and researchers in Tel Aviv’s Gray Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences and the Fleischman Faculty of Engineering, as well as Ichilov’s Sagol Brain Institute. It was published in August in the peer-reviewed Communications Psychology.

Schmidig said that the researchers tracked where people looked while watching short movies in a method called Memory Episode Gaze Anticipation (MEGA). When people watched the same clip more than once, their eyes started moving just before important events happened on screen, showing that their memory was predicting what would come next.

In the study, 145 healthy subjects watched animation videos that included a surprising event, such as a mouse suddenly jumping out of the corner of the frame. Tracking the subjects’ eye movements through two separate viewings of the same films, the researchers found that during the second viewing, subjects shifted their gaze toward the area where the surprising event was about to occur.

A comparison of eye movement data with verbal memory reports indicated that the gaze direction was, in fact, a more accurate measure: In some cases, subjects said they did not remember the mouse, yet their gaze indicated that they did.

Using AI learning programs, the scientists also found that different eye movements showed different types of memory. Looking ahead to events showed recall of details, while changes in pupil size signaled a sense of familiarity.

Schmidig said that he has been working for over a decade on this new approach.

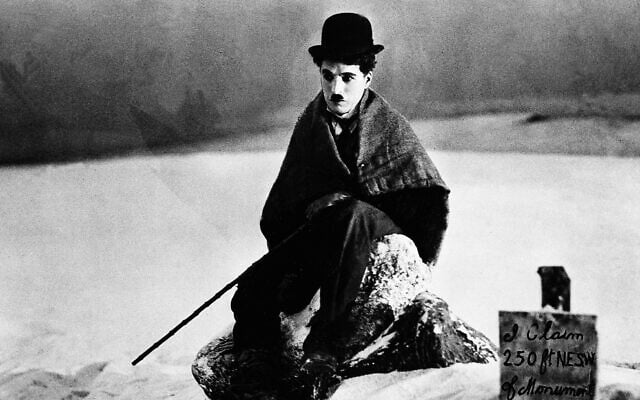

For this study, the scientists at first used short comedic clips of the actor Charlie Chaplin.

“The second time you watch the clip, you know what’s going to happen, and you look differently,” Shmidig said. “You anticipate and expect something to happen at a specific location in time.”

The scientists then worked with an animation studio in Tel Aviv to create 60 animated videos. With these and 100 videos from YouTube, the researchers tracked the subjects’ eye movements by where they looked on the screen.

In this way, Schmidig said, “We have a measure of memory.”

“The study proves that tracking eye movements can be an excellent alternative to verbal questions such as ‘Do you remember this?'” said researcher Yamin. “Sometimes people remember, but can’t say that they remember. By using AI machine learning techniques, it is possible to infer automatically, from just a few seconds of eye tracking, whether someone has seen a video before and formed a memory of it.”

Schmidig said he has always been curious about when memories start, and is now involved in ongoing studies in Tel Aviv and Zurich to study when memory actually starts.

”Does it start earlier than what we think right now, before children can talk?” the scientist wondered out loud. “Until now, scientists have mixed the ability to report and memory itself. This new technique allows us to tear the two apart. Thus, it is possible that, for example, autistic children have more memories than they can tell us.”

The same could be true with Alzheimer’s patients.

“They probably have more memories, but the issue is to access them and express them in words,” he explained.

Schmidig said this sort of memory test could become a preliminary way for doctors to evaluate people after a stroke or brain injury, or even to predict Alzheimer’s progression.

He hopes that the scientists will be able to develop a computer program that can be done on a laptop at a doctor’s office, with no need for “a trained expert,” to test people’s memory and brain function.

”It’s very easy, very fast,” he said. “It takes 15 minutes for the first viewing and then 15 minutes again,” and within half an hour, experts should have an objective indication of a subject’s memory capability.

“I’m not surprised by the results. I’m more surprised by how well it worked,” he said.

During the study, subjects sometimes told the scientists they didn’t know what was going to happen next in the movie.

“But their eyes know,” Schmidig said.