The controversial approval earlier this month of plans to finally build a large extension of the Maale Adumim West Bank settlement in the E1 corridor marked a rare occasion in which the settler movement and the Israeli left came into agreement; both sides confidently asserted the project would strike a fatal blow to the idea of a Palestinian state.

Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich hailed the approval by the Civil Administration, a department of the Defense Ministry, as an “historic” moment that “practically erases the two-state delusion and consolidates the Jewish people’s hold on the heart of the Land of Israel.”

At the same time the Peace Now organization, a veteran campaigner for a two-state solution, said the project threatened the viability of a future Palestinian state and would lead to a “binational apartheid state,” while Democrats MK Gilad Kariv said it endangered Israel’s ability to ever separate from “millions of Palestinians” in the future.

The slated project to build in the E1 corridor has long been considered a severe threat to the viability of Palestinian state, and that remains true even during the current era, when reaching a two-state solution appears to be as distant as it ever has been.

But just why is the project considered such a danger to that notion, and is that claim justified?

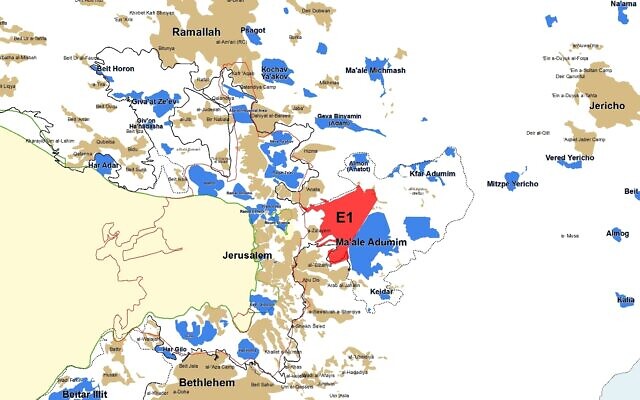

The E1 corridor or zone is an area of some 12 square kilometers (4.6 square miles) in the West Bank, east of East Jerusalem and west of Maale Adumim. The land is inside the jurisdictional boundaries of Maale Adumim, and any construction there would become part of the existing settlement city.

The plans approved by the Civil Administration’s Higher Planning Committee last week would see 3,412 housing units built in the E1 zone. This would likely provide housing for between 12-to-15 thousand extra residents of Maale Adumim, the current population of which is some 38,000 people.

Critically, E1, Maale Adumim and Jewish East Jerusalem neighborhoods constructed over the Green Line constitute a dividing block between the Palestinian cities of Ramallah to the north of Jerusalem, Bethlehem to the south, and the Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem.

The plan to build in E1 was first conceived by the Shamir government in 1991 and advanced by the Rabin government in the mid 1990s.

Israel’s goal in advancing the project was to connect Jerusalem with Maale Adumim through E1, create Israeli territorial contiguity around the capital, and thereby prevent Palestinian demographic and urban expansion from “strangling” Jerusalem.

But the plan was halted under the Rabin administration due to American objection, and has remained stalled ever since, despite several efforts to revive it, notably by Ariel Sharon in 2004.

Now that the plans have finally been approved, it will likely take several months at least before tenders are published to allow contractors to bid for the construction contracts.

After that, it will likely take several more months to evaluate the bids and award the contracts.

The Peace Now organization estimated that if things proceed rapidly the construction could begin in about a year, although the process may take longer.

The prime minister, the housing minister, and the government in general also have the power to delay construction, if they so wish.

There are two major concerns over construction in E1 held by the Palestinian Authority and proponents of a Palestinian state.

The first is that the development would severely disrupt the territorial contiguity of any future Palestinian state or entity, due to its location and the topography of the surrounding area.

Although in theory there are 20 kilometers (nearly 12.5 miles) between the eastern edge of Maale Adumim and the Jordanian border, the topography of the land east of Maale Adumim descends steeply and dramatically down towards the Jordan Valley.

In practice, this would mean that to travel from Ramallah to Bethlehem, a long circuitous route would need to be established that would necessitate driving into the Judean Desert, down to the Jordan Valley and back up again, involving a descent of some 1,200 meters (almost 4,000 feet), and a similar ascent in just one journey.

It is not even clear if such a route could be established, given the acutely steep escarpment of the Jordan Valley east of Maale Adumim.

Israel is developing what is called the “Fabric of Life” road, which would create a road solely for Palestinians to facilitate movement between the southern and northern West Bank, although critics of the government argue that it does too little to ensure the territorial viability of a future Palestinian state, if Israel were to build in E1.

Daniel Seidemann, an Israeli attorney specializing in the geopolitics of Jerusalem, said the construction of the E1 project would therefore drive a wedge through the West Bank and the putative Palestinian state, fragmenting it into northern and southern regions.

“You can see today just how stunted Palestinian economic development is already, in large part due to restrictions on movement, and use of the public domain, and resources in the West Bank,” said Seidemann.

Seidemann and others argued that the dividing wedge that would be created through the development of E1 would further stifle Palestinian economic development in the broad metropolitan areas of Bethlehem, East Jerusalem, and Ramallah, where much of the West Bank Palestinian population lives.

The second major effect of construction in E1 would be broadly cutting off the Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem from the rest of West Bank.

Jerusalem neighborhoods across the Green Line, such as Gilo, Har Homa, and the under-construction Givat Hamatos in the south, as well as Neve Yaakov and Pisgat Ze’ev in the north already served to divide the contiguity of Palestinian East Jerusalem.

Development in E1 would further cut off those neighborhoods from the rest of the Palestinian population, thwarting the Palestinian goal of having East Jerusalem serve as the capital of its future state.

This would severely impinge on the “statehood” of a future Palestinian state, said Seidemann, comparing the future borders of such an entity under these conditions to the Bantustans of apartheid-era South Africa, which were a set of disparate, disconnected territories with tortuously drawn borders for black South Africans.

The severity of these problems generated a wave of diplomatic condemnation upon approval of the E1 development, precisely because of the detrimental effect it would have on the viability of a future Palestinian state.

The EU’s top diplomat Kaja Kallas said the E1 plan “undermines the two-state solution, and added that, if implemented, settlement construction in E1 would “permanently cut the geographical and territorial contiguity between occupied East Jerusalem and the West Bank and sever the connection between the northern and southern West Bank.”

Twenty-five European and Western-aligned nations also condemned the plans, citing Smotrich’s declaration that it would divide the West Bank and restrict Palestinian access to Jerusalem.

The plan was also denounced by Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and other Arab nations for the same reasons.

Michael Koplow, of the New York-based Israel Policy Forum think tank, agreed that the E1 plan is problematic, to say the least, for any future plans for a two-state solution, and even said he understood why some people would see it as “catastrophic.”

Like others, Koplow said E1 “completes the encirclement of the Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem” and severely disrupts Palestinian territorial contiguity.

Beyond those criticisms, he also argued that further increasing the amount of land to be included in land swaps from the West Bank to Israel under any future deal creates difficulties, since there is little more available land in Israel to transfer in return to the Palestinians.

But, opined Koplow, the E1 project is not a “doomsday scenario” that makes separation from the Palestinians impossible.

He pointed out that the vision of a two-state solution always had Gaza and the West Bank as part of one Palestinian state, despite the large geographic divide between those two territories.

“That was never seen as fatal to a two-state solution, so a longer route between the northern and southern West Bank doesn’t seem to be such a problem,” said Koplow.

He said that various engineering solutions have always been envisaged as part of efforts to divide the region, including tunnels, overpasses, and bridges to connect the various proposed parts of the Palestinian state.

Indeed, several tunnels already connect Palestinian villages and East Jerusalem, he pointed out.

“Separation from the Palestinians will always involve a burden on both populations, that was always going to be the case, whether under the 1947 partition plan, the Oslo Accords or future arrangements,” Koplow continued.

“I don’t view it as a final nail in any coffin.. I don’t think it makes two states an impossibility.”

Seidemann was far less sanguine about the impact of E1 on the viability of a Palestinian state, quipping that there are “only so many times you can cut the worm in half before the worm stops wiggling.”

But, beyond the physical impact of the slated settlement project, he argued that the willingness of the government to advance such a controversial project despite the consequences, including the diplomatic condemnation, indicates just how far the current Israeli governing coalition is willing to go in its efforts to assert control over the entire territory between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River.

“For Smotrich, Itamar Ben-Gvir and their ilk, this is about the assertion of Israeli sovereignty over all areas of the West Bank. They’re saying ‘We’re going to show you that we’re sovereign here,’” said Seidemann.

And whereas Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in the past was more pragmatic and unwilling to jeopardize Israel’s diplomatic standing, the power of the ideological right-wing in the current government and his precarious political position has led Netanyahu to abandon his previous restraint.

“This Netanyahu is not the wimp we came to know and love; it’s all about his political survival, said Seidemann.

“If it were not for Smotrich and Ben Gvir, he would continue to kick the can down the road. The reason he isn’t now is that Smotrich and Ben Gvir are holding on to Netanyahu by his sensitive parts,” he added wryly.

But it is precisely because of the explosive impact the E1 development may have on Israel’s international relations, and the project’s dependence on Netanyahu’s unstable political position, that means there is a chance it may yet face further delays.

If Netanyahu’s government falls or elections are called before construction on E1 begins, then Smotrich’s plans may yet face further obstacles.