Israel’s attack on Iran in the early hours of June 13 saw over 200 Israeli Air Force fighter jets attack some 100 Iranian targets, including Tehran’s nuclear facilities, ballistic missile targets, key members of Iran’s military forces, and nuclear scientists.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu justified the surprise attack on the basis of Iran’s extensive nuclear program, alleging that Iran was approaching a weaponization threshold and was an imminent existential threat to the Jewish state. Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar further pointed to Tehran’s decades-long policy of funding and arming terror proxies and directing them to attack Israel, and other hostile Iranian acts.

Yet despite this reality, several scholars of international law have challenged the imminence of Iran’s threat to Israel, a key condition for a preemptive strike, and argued that Tehran had neither the capability of firing a nuclear weapon at Israel at the time of the attack or the proven intent to do so, two other crucial requirements for anticipatory military action.

Critics have also challenged whether the launch of Israel’s attack was the last opportunity to prevent a feared Iranian strike, arguing that non-military alternatives, such as diplomacy, had not been exhausted.

So does Israel’s campaign of airstrikes, dubbed Operation Rising Lion, really fail these key tests of international law for justifying a resort to military attack? Or are there broader interpretations of the legal requirements, or even a different framework entirely, that gave Israel grounds for its unprecedented war against Tehran?

On the morning of June 13, Netanyahu outlined the reasons for embarking on the attack on Iran, asserting that Iran had enough enriched uranium to produce nine nuclear bombs, and that it had taken steps to weaponize this nuclear material in recent months that it had never done before. Netanyahu described this as a “clear and present danger to Israel’s very survival.”

Iran has for decades persistently developed its nuclear program, enriching uranium to ever higher degrees, far beyond what it needs for civilian purposes, while allegedly developing the means to weaponize it, according to Israeli intelligence.

As a result of this, Israel attacked Iran’s nuclear facilities and assassinated scientists working on its nuclear program, the prime minister said.

Netanyahu also detailed what he alleged was Iran’s plan to build 10,000 ballistic missiles, which he said was an intolerable threat that must also be stopped.

In a letter to the UN Security Council on Tuesday, Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar also pointed to Tehran’s use of proxies to attack Israel and to its previous missile barrages against Israel, saying that Jerusalem was in an ongoing war against Iran and implying that there was therefore no requirement to meet the standards of a preemptive strike.

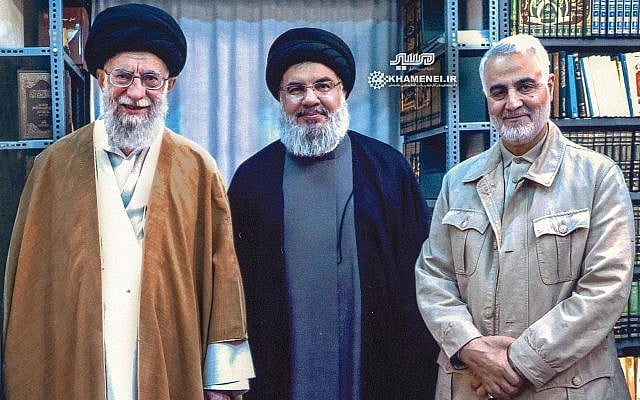

Sa’ar also referred to Iran’s genocidal rhetoric, including that of its Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei who as recently as this May described Israel as a “cancerous tumor” which he threatened would be “eradicated.”

Writing for the blog of the European Journal of International Law, Prof. Marko Milanovic of Reading University argued that Israel’s attack was explicitly a preemptive strike to prevent Iran from developing a nuclear weapon that could be used against Israel.

But he argued that Israel’s preemptive strike failed to meet three key conditions, namely that the country subject to the preemptive strike have the capability to attack, and have the intent to attack, and that the moment of the preemptive strike be “the last window opportunity” to prevent the enemy country’s attack.

Milanovic insisted that Operation Rising Lion could not meet the standard of preventing an imminent nuclear attack, since Iran has yet to develop a nuclear weapon, in reference to the capability condition.

And Milanovic said Israel’s air campaign would not even meet a less stringent view of “imminence,” since, he argued, there is insufficient evidence that Iran intended to attack Israel with a nuclear bomb, or that June 13 was the last opportunity to stop it from doing so.

“There is little evidence that Iran has irrevocably committed itself to attacking Israel with a nuclear weapon, once it develops this capability,” contended Milanovic.

Noting that even Netanyahu said in his video message the morning of June 13 that Iran was still months away from building a bomb, and that negotiations between the US and Iran over Tehran’s nuclear program were underway, he said he did not see “how it could plausibly be argued that using force today was the only option available.”

Prof. Ben Saul of the University of Sydney made similar arguments in an article for The Guardian, arguing, “Inflammatory and even genocidal rhetoric by Iranian officials” did not equate to a concrete plan to launch an imminent nuclear attack.

Since, Saul argued, there was no imminent attack, there was still time “to pursue non-violent means to address the threat,” including action by the UN Security Council, sanctions, and diplomacy, noting that the US and Iran were in the midst negotiations over its nuclear program when Israel launched its attack.

Speaking to The Times of Israel, Prof. Robbie Sabel of Hebrew University agreed that it was impossible for Israel to prove there was an imminent Iranian nuclear attack against Israel, since Tehran has yet to build such a weapon, and said it would still take Iran a significant period of time to complete the weaponization process for a nuclear bomb.

He did posit that when trying to prevent an attack by weapons of mass destruction the requirement of imminency may be less stringent, since waiting until a country has developed that capacity could make it too late to strike.

And Sabel dismissed the idea that the negotiations between the US and Iran could have effectively curbed its nuclear program, pointing out that such negotiations have been conducted off and on for decades with Tehran never having given up its enrichment facilities.

“They always insisted on their right to enrich uranium even in the current negotiations, and there is no great difficulty in reaching 90 percent enrichment from the 60 percent they already do,” said Sabel, in reference to the necessary level of enriched uranium for a nuclear bomb.

Addressing the issue of intent, Prof. Michael Schmitt of the United States Military Academy at West Point argued in an article on the Articles of War blog that given the repeated rhetoric of annihilation against Israel coming from numerous Iranian leaders over many years, it was “not unreasonable” to conclude that Tehran would carry out its threat if it obtained the capability to do so.

“If there is a degree of uncertainty as to whether Iranian leaders mean what they say, the risk of being wrong should be shouldered by the side making the threatening statement,” asserted Schmitt.

He added, like Sabel, that given the existential threat to the Jewish state, Israel should have more leeway in conducting its attack against Iran since “the threat of being wrong is undeniably existential.”

And he argued that due to the risk posed by nuclear weapons, the condition that Iran have the capability to attack could be fulfilled by the likelihood it would acquire that means of attack in the near future.

Although Schmitt concluded that Operation Rising Lion “did not fulfill the preconditions for anticipatory self-defense” under the “traditional” definition, he argued that a “liberal interpretation” of each of the requirements of capability and last window of opportunity might comply with a less rigid standard for a preemptive strike that has supplanted the old understanding in recent years.

But Sabel argued that arguments over whether Israel had a legal right to resort to force on June 13 are superseded by the fact that Israel and Iran were already at war, meaning that the launching of Operation Rising Lion was merely part of that war and therefore did not require any particular legal justification.

“Iran armed its proxies, encouraged them to attack Israel, and those proxies acted under guidance from Iran when they attacked us,” he said, noting as well the April and October 2024 Iranian missile barrages against Israel.

Iran attacked Israel with massive barrages of ballistic missiles twice in 2024 — after Israel targeted a key Iranian general in Damascus in April that year, and then assassinated Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in September.

“This constitutes an armed attack by Iran,” he continued, and said that within this armed conflict it was “perfectly legitimate” to hit Tehran’s nuclear program, albeit in a fresh campaign.

Milanovic argued against this rationale, contending that even if there were an ongoing armed conflict between Israel and Iran, “most” of the Iranian attacks against Israel were over, and even if they continued were of “minimal intensity” and “could not justify an all out assault on Iran’s nuclear program.”

But in his letter to the UN Security Council, Sa’ar used the argument that Israel and Iran were already engaged in an ongoing conflict in explaining the launch of Operation Rising Lion.

Sa’ar insisted that the plethora of Iranian hostile acts against Israel over many years and especially in recent months meant there was no doubt Israel was in an ongoing, intense armed conflict with Tehran that justified Israel’s latest campaign.

He pointed to what he described as Iran’s “extensive network of terrorist proxies surrounding Israel” and said that Tehran, through its Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, has been “substantially involved in its proxies’ persistent and unlawful attacks against Israel.”

And he pointed to the Iranian barrages in April and October last year as further examples of Iranian attacks on Israel.

“Israel, as the Jewish homeland, cannot and will not accept the threat of extermination,” wrote Sa’ar.

“Iran’s ongoing aggression poses an existential threat to Israel and a grave threat to international peace and security.”