David Levy, a longtime Likud politician known for breaking the glass ceiling for Mizrahi Jews in Israeli politics, died on Sunday evening at the age of 86.

Although younger Israelis may not recognize his name, David Levy played a central role in breaking down social and economic barriers to Mizrahi (Jews of Middle Eastern and North African origin) political involvement in the 1970s and 1980s, in addition to solidifying Likud’s working-class Mizrahi voter base, which remains until today.

Born in Rabat, Morocco, Levy immigrated with his family to Israel in 1957, one year after Moroccan independence. They settled in Beit She’an, a northern development town, where he lived until his death.

Levy initially made a living by working on Ashkenazi-dominated kibbutzim in the surrounding area. His entry into the political world was a direct result of his labor organizing activities, beginning with a strike he organized against kibbutz leadership until they guaranteed their workers clean, cold water to drink.

After the strike, he was blacklisted from working in the Beit She’an area, so he searched for work elsewhere, eventually securing a job as a construction worker in Tel Aviv.

Levy anchored himself in union politics for the years to come, joining the right-wing Tekhelet-Lavan (Blue-White) faction of the Histadrut, Israel’s national trade union.

In 1965, Levy won a seat on the Beit She’an local council as part of the Gahal alliance led by Menachem Begin. Four years later he placed 24th on Begin’s list, narrowly making it into the Knesset during a decisive Alignment victory after the Six Day War.

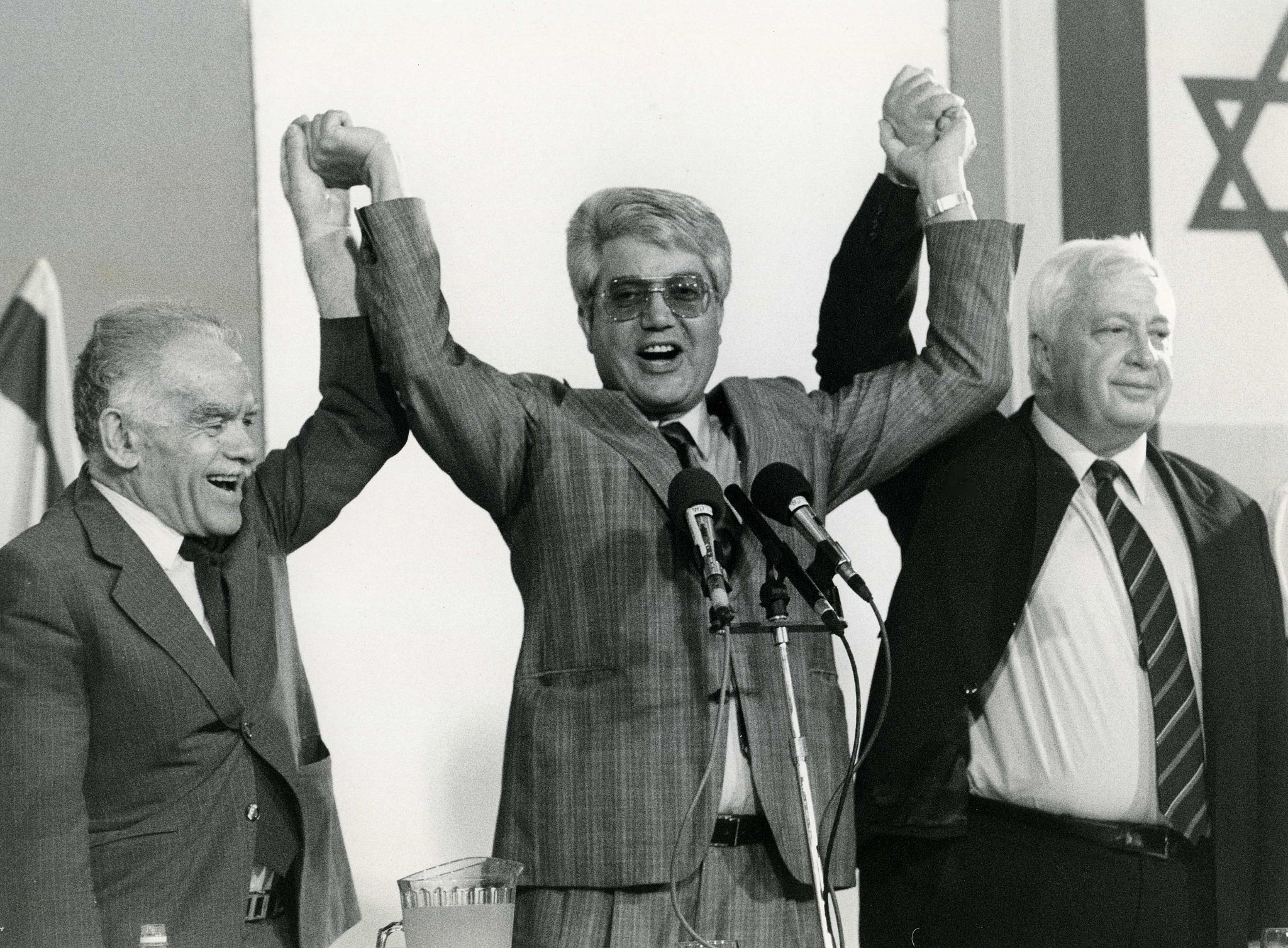

Following a landslide victory in 1977 for Begin’s Herut party, now modern-day Likud, Levy was able to leverage his proximity to the Mizrahi working class and act as an intermediary between it and the prime minister.

Preceded by more radical Mizrahi movements such as the Israeli Black Panthers, which made waves in the 1970s without much electoral success, Levy favored integration into the Israeli political establishment.

Levy’s effort to secure economic benefits for Mizrahi communities is perhaps the most enduring aspect of his legacy. Likud’s resulting success in creating a Mizrahi middle class solidified the community as its core constituency, an electoral trend that continues to this day.

“Polls showed enormous support for the Panthers, but people were not prepared to vote for them. The person who identified this was David Levy, who was until then almost unknown,” explained Sami Shalom-Chetrit, a scholar of Mizrahi social movements, to Davar Magazine in 2021. “There is no David Levy without the Panthers, there is no Likud as a popular movement without the Panthers.”

During his tenure as construction and housing minister in Begin’s first government, Levy alleviated housing shortages in Mizrahi neighborhoods in Jerusalem by incentivizing young couples to relocate to settlements in the occupied territories in the West Bank.

He also ramped up construction and funding in economically depressed neighborhoods as part of the government’s ambitious “neighborhood rehabilitation” initiative.

As he rose to prominence as a minister in successive right-wing governments, Levy faced considerable racism from both the media and his fellow party members, dismissed as a “national joke” on the sole basis of his Moroccan background.

Israel’s famous 1990s political satire show, “Harzufim,” flattened his political life into a one-word catchphrase, which his caricature repeated to no end — “mufleta,” a food traditionally eaten during Mimouna, a post-Passover dinner celebration observed by North African Jews.

“I was, in the mouths of some people in Likud, like a monkey who had just come down from the trees,” Levy said in an iconic 1992 speech, following his loss to Yitzhak Shamir in Likud’s leadership primaries.

In the middle of Likud primaries a year later, Levy’s then-opponent, now Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, cast him as the culprit in an alleged blackmailing scandal, in which the latter received an anonymous call threatening him to drop out of the race, or else a tape (never uncovered by police during the investigation which followed) of him cheating on his wife be released to the press.

Netanyahu, implying that Levy orchestrated the call, referred to him as “one man, surrounded by a group of criminals.”

Understood by political analysts in hindsight as a ploy by Netanyahu to smear his opponent, the “Hot Tape Affair” as it came to be known, set Netanyahu on the path to the premiership and served as a massive blow to Levy’s political future.

Known for his more moderate political outlook compared to many of the “Likud princes” — the second-generation right-wing politicians who came to dominate the party in the 1990s — Levy took issue with what he called the “rampage and hooliganism” of many on the right in the leadup to Yitzhak Rabin’s murder.

During the infamous 1995 Zion Square rally against Rabin, Levy was one of the few to leave the stage after witnessing demonstrators portray Rabin as an SS officer and call for his death.

After his loss in the 1993 primaries, Levy split from Likud and founded his own party, Gesher, which he united with Likud in 1996.

Following another fallout with Netanyahu over his government’s policies toward the lower class, Levy resigned as foreign minister in his government, only to return in 1999 to the same post under Ehud Barak.

He resigned from Barak’s government as well, in opposition to what he viewed as an overly conciliatory approach to the peace process.

After 37 consecutive years in the Knesset, Levy lost his seat in the 2006 elections, subsequently ending his political career.

Levy is survived by his wife Rachel and 12 children, including politician Orly Levy-Abekasis, who was most recently a Knesset member for the Likud party, but has since exited politics.