This week, the International Association of Genocide Scholars announced that it had passed a resolution determining that Israel was guilty of genocide in Gaza, according to international law.

As part of its evidence, the association cited a slew of human rights groups that had come to the same conclusion — that the Jewish state had perpetrated the crime of crimes.

The statement did not note, however, that some of those conclusions were based on reinterpretations of the legal definition of genocide, and not the established reading of the law cited in the association’s resolution.

By including the findings of the outside groups in its attention-grabbing resolution, the association played into what critics say is a longstanding pattern of international groups reinterpreting international legal definitions in accusations leveled against Israel, including charges of alleged apartheid, and claims related to Palestinian statehood and the status of refugees.

According to supporters of Israel, these reinterpretations are biased attacks against the Jewish state that chip away at international norms. Those in favor of the changes, meanwhile, describe them as an acceptable and necessary update to laws formulated in the ashes of World War II.

“It’s completely eroding international law and standards. Words no longer matter, laws no longer matter. What’s the point of having laws on the books and definitions that you can change whenever you want?” said Mark Goldfeder of the National Jewish Advocacy Center legal group. “From a more sinister perspective, if you apply the law everywhere in one way, but differently when it comes to the Jewish state, there’s a word for that.”

Orde Kittrie, a former attorney at the US State Department who now teaches law at Arizona State University, said the effort to change definitions to fit Palestinians’ claims had long been promoted by Ramallah before the issue became supercharged by the Gaza war.

In 2011, Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas advocated for “the internationalization of the conflict as a legal matter.”

“Part of that is, if there’s a crime that you want to accuse Israel of and Israel doesn’t fit the definition, ‘I’ll change the definition,'” said Kittrie, who is also a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

The International Association of Genocide Scholars resolution declared Israel guilty as per the United Nations Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. But its decision cited reports by groups, including Amnesty International and B’Tselem, which argued that Israel was guilty of genocide even if its actions did not meet the “narrow” standard accepted by the UN.

Genocide in international law is determined by a strict legal definition, with a high threshold for proof, particularly when determining intent. The Genocide Convention, a 1948 UN agreement, defined genocide as the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.”

Determining a motive is rarely a requirement in criminal law. If a suspect is charged with robbing a bank, prosecutors do not need to determine his motive to convict him, only that he committed the crime. An exception is hate crimes, where prosecutors need to prove a perpetrator was motivated by bias against a group. Like genocide, the bias requirement for hate crimes is difficult for prosecutors to prove.

The UN’s International Court of Justice (ICJ) has said that, absent evidence of a genocidal plan, prosecutors must infer intent from the pattern of a state’s actions, and that genocidal intent must be “the only inference that could reasonably be drawn from the acts in question.” If a party in a conflict intends to defend itself, and also contributes to the destruction of a group, it does not constitute genocide.

Amnesty sidestepped this definition to determine Israel was guilty of genocide by redefining the term in a report last year.

On page 101 of the 296-page report, Amnesty said it considered the established definition of genocide “an overly cramped interpretation of international jurisprudence and one that would effectively preclude a finding of genocide in the context of an armed conflict.”

B’Tselem, in its report accusing Israel of genocide, complained that the “legal definition is narrow,” and that past cases of genocide “do not align with the stringent legal definition.”

“This report relies on the legal definition of genocide as outlined in the UN Convention, but adopts a broader analytical framework,” the report said.

Sara Brown, a member of the genocide scholars association who criticized its Gaza resolution, called the use of outside groups’ findings to underpin genocide determinations a form of “citation washing.”

“It’s so hard to trace those sources all the way back to their origins. It’s so muddled,” she said. “How many people are going to actually do the work to see the resolution, to ask about the process? No, they’re going to see that, ‘Genocide experts agree.’ Well, we don’t.”

A spokesperson for the association said its scholars based their work on the UN genocide convention, though most members abstained from voting on the resolution.

“In terms of the scholarly community, there is a relationship between each scholar and the way that they define genocide,” said spokesperson Emily Sample.

According to Brown, the association no longer requires members to be scholars or have credentials, allowing agenda-driven activists into the process.

Last year, the Irish government sought to reinterpret the definition when Ireland joined South Africa’s case, accusing Israel of genocide at the ICJ.

Then-Irish Minister of Foreign Affairs Micheál Martin said, “Ireland will be asking the ICJ to broaden its interpretation of what constitutes the commission of genocide by a state.”

In its submission to the ICJ, Ireland sought to broaden the definition of intent, arguing that a perpetrator of genocide need not have that “purpose” to be guilty, only to know that a “probable consequence” of their actions could contribute to the destruction of a group.

Supporters of the legal reinterpretations argue that the updated definitions are necessary to account for various ways the world has changed since World War II.

Philippe Sands, an international legal scholar who has appeared before the ICJ, argued in an interview last month with The New York Times that a broader definition for genocide was more in line with the meaning of the term as originally conceived.

“My own personal view is that definition is wrong. It sets the bar far too high,” Sands said of the language adopted by the ICJ. “To say that you’ve got to have only one intent makes it very, very difficult to prove.”

Looming large over the debate is the Holocaust, which formed the impetus for the establishment of the international legal system and the outlines for crimes against humanity. The term genocide was coined by the Polish Jewish attorney Raphael Lemkin in 1944 because no terminology in international law captured the enormity of the crime. The Nazi genocide remains the archetype of genocide and the model on which the Genocide Convention is based.

Both sides have pointed to the irony of using that legal system to accuse the Jewish state of genocide. Israel’s opponents accuse the state of becoming the perpetrator of genocide, while its defenders say a legal system established on the ashes of Jewish genocide victims is being weaponized against Jews.

“The Nazis began by changing the law to make antisemitism lawful and corrupting the judiciary to apply those discriminatory laws. History is repeating itself. UN ‘investigations’ are defined to find the Jewish state guilty,” said Anne Bayefsky, president of the Human Rights Voices nonprofit and director of the Touro Institute on Human Rights and the Holocaust. “All of it does enormous lasting damage to the rule of law for everyone.”

But Prof. A. Dirk Moses, a genocide scholar at the City College of New York, said the law was continually evolving based on interpretations employed by the ICJ.

“ICJ jurisprudence develops with each case; it’s not set in stone, in particular because the ICJ is not bound by previous judgments,” Moses told The Times of Israel.

Critics contend that many redefinitions do not refine the law in line with ICJ rulings but rather seek to deliberately tailor meanings to Palestinian claims, including allegations that Israel’s policies amount to apartheid.

The International Criminal Court’s 1998 Rome Statute defines the crime of apartheid as “systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group.” The UN’s Genocide Convention of 1976 also defines apartheid based on racial discrimination.

However, in a 2022 report focused on Israel, Amnesty sought to stretch the definition of apartheid to bypass the lack of evidence of racial segregation in Israel, arguing that race was a social construct and thus irrelevant.

“The concept of distinct human races has been discredited,” reads a passage from the 278-page report, which also claims that the Rome Statute and Genocide Convention had not defined “racial group,” and that the Amnesty report had adopted a “subjective understanding” of the term.

Human Rights Watch, accusing Israel of apartheid in 2021, argued for a “broader conception of race” to fit the apartheid definition.

Critics argue that reinterpretations used to pressure Israel are part of a longstanding pattern toward Israel in international forums.

In the 1998 Rome Conference that established the International Criminal Court, for example, Arab states added a clause that made Israeli settlements a war crime by changing the definition of the “transfer of population.”

The UN’s 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees included a special article for the Palestinians, defining their case differently from other groups by granting refugee status to their descendants.

And some have charged that a push by Western states to recognize Palestinian statehood in response to Israel’s Gaza campaign ignores the Montevideo Convention, a 1933 treaty that established requirements for statehood.

Palestine does not meet any of the four requirements, according to 40 members of the UK’s House of Lords.

UK Trade Secretary Jonathan Reynolds has dismissed such criticism as “missing the point.”

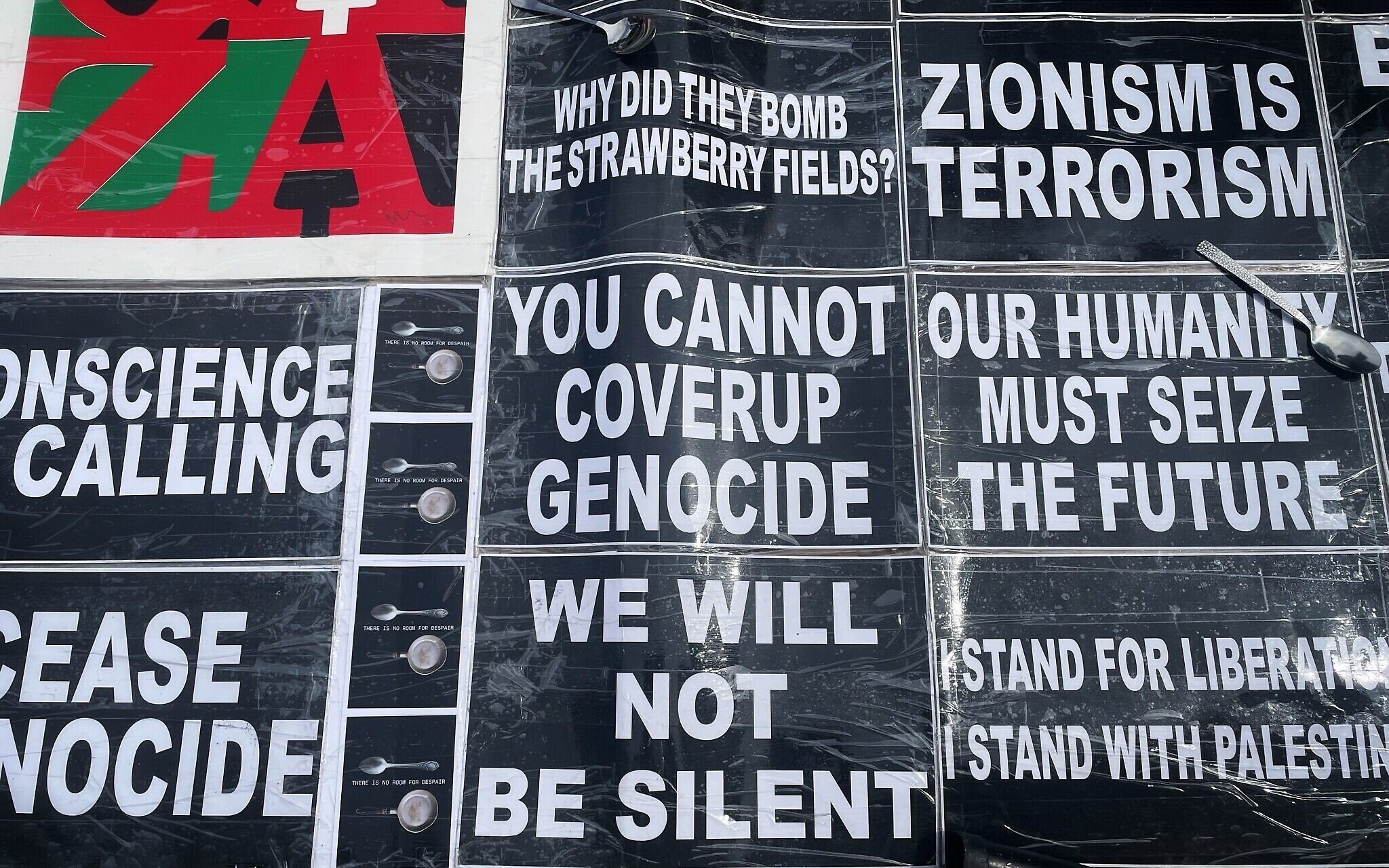

Human rights monitors like Amnesty and Human Rights Watch do not have formal legal authority, but their reports garner widespread media coverage that drives public discourse. The allegations are picked up by politicians and protesters and used to demonize Israel, with no attention paid to the fact that they employ changed definitions.

Their conclusions are also used by the UN and to build cases in international courts, which could result in the formal codification of their changes.

In 2021, weeks after Human Rights Watch accused Israel of apartheid, the UN established a Commission of Inquiry to investigate Israel, citing charges of apartheid. The commission’s reports have cited heavily from Amnesty and Human Rights Watch.

“The UN basically borrowed that new definition and said, ‘Okay, Commission of Inquiry, see whether Israel has committed the following,'” Kittrie said.

“This is what happens. Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, they will advocate these definitions. Then they will advocate for international, intergovernmental organizations, the UN, etc., to adopt them, and they often meet with success,” Kittrie said.

South Africa’s submission to the ICJ charging Israel with genocide cited Amnesty and Human Rights Watch more than 10 times and freely used the term apartheid.

“It matters because it’s all an incestuous cycle. Amnesty does it, and then they’re quoted by B’Tselem, and then they’re quoted by someone else,” Goldfeder said. “It becomes this self-citing thing.”

“They all are relying, if you go back down to the source, on a crazy change in definition, that’s literally on page 101 of their report that says, ‘Yeah, we didn’t like the definition of the law, so we changed it,” he said.

Prof. Shannon Fyfe, a scholar of legal philosophy, ethics and international conflict at the Washington and Lee University School of Law in Virginia, said reinterpretations of genocide like Ireland’s were not counter to the wording of the law, though, only to previous interpretations.

“This is an area where there is minimal jurisprudence, and none of the precedent in these international courts is legally binding on future decisions,” Fyfe said. “They are arguing for a different interpretation, likely due to the fact that the current standard for establishing genocidal intent is hard to meet.”

To formally change the definitions of international crimes, the treaties establishing those definitions would need to be amended, a difficult process that has not happened, Kittrie said.

“These redefinitions, they’re not taking advantage of, shall we say, ambiguity in the wording of the treaty. They’re really doing violence to the language of the treaty,” Kittrie said. “They’re not trying to change the wording of the treaties. Instead, they are saying, ‘Well, black means white. Yeah, the treaty says this, but the real definition is this other thing.'”

According to Fyfe, the legal authorities have not yet formally adopted the expanded definitions. The ICJ has not adopted the changed definition or found Israel guilty of genocide and the case will likely take years to resolve.

While a finding of genocide against Israel would not automatically redefine the crime in the Hague, due to the court not being bound by precedent, the same cannot be said for the court of world opinion, where the meaning of humanity’s most heinous atrocity may already be undergoing revision to Israel’s detriment.

“I have not seen legal institutions doing this reinterpreting,” Fyfe said, “but the legal institutions and what they are saying is such a narrow slice of what we see in the news.”