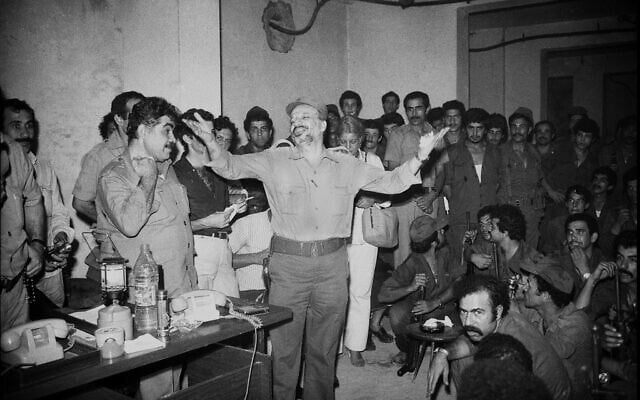

Ehud Yaari remembers standing at the Port of Beirut in late August 1982, watching as Yasser Arafat boarded a ship and left Lebanon along with thousands of Palestine Liberation Organization fighters under an internationally brokered agreement meant to end a war with Israel.

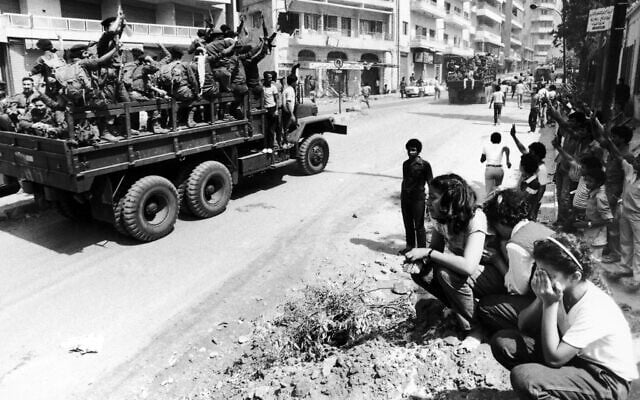

At the time, Yaari said, the PLO’s exit from Beirut was seen as a major Israeli achievement. Israel had invaded its neighbor to the north nearly three months earlier with the declared goal of halting cross-border terror attacks carried out by Palestinian groups, a decision that sparked controversy both at home and abroad.

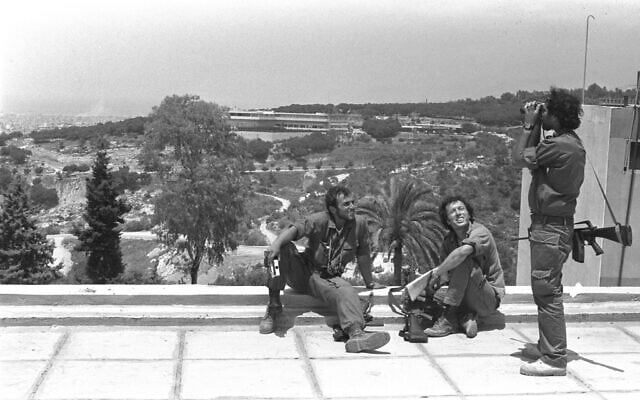

The army quickly besieged western Beirut and gradually intensified its bombing campaign as the summer wore on. Facing local and international pressure, Arafat eventually agreed to evacuate the PLO’s headquarters and take the group out of Lebanon altogether, ostensibly removing a threat from close to Israel’s borders.

“It was clear that it was an Israeli victory,” said Yaari, a longtime Israeli journalist and commentator who had reported from Beirut. “At the moment the PLO left Lebanon, that was the goal.”

More than four decades later, Israel appears poised to repeat the feat with another Palestinian terror group, Hamas, potentially removing or at least mitigating a major threat on its border. The peace plan proposed by US President Donald Trump and endorsed by Israel would require Hamas to disarm and give up control of the Strip. It offers safe passage out of Gaza for Hamas operatives who wish to leave.

The first part of the plan was agreed to on Wednesday, paving the way for the release of hostages in the coming days.

As Israel and Hamas negotiate the details of the subsequent stages of the plan, analysts say the PLO’s 1982 departure from Lebanon could offer a useful parallel to a Hamas evacuation of Gaza — though it also differs in core respects.

The PLO’s exit, they say, may show how and why an embattled Palestinian terror group would agree to cede power and a home base. But it also serves as a cautionary tale about what pitfalls and dangers Israel may face in the months and years ahead.

“The parallel is that here too Hamas is under heavy pressure, because everyone tells them, ‘We need to stop the bloodshed in Gaza, and it’s your own responsibility,’” said Eyal Zisser, a Middle Eastern history scholar who is Tel Aviv University’s vice rector.

Trump’s plan, Zisser added, offers “a way to ensure the survival of the [Hamas] leadership [that is] left, and a new beginning somewhere else.”

From the terror group’s perspective, he said, “It’s not a suicide. It’s giving up, but not a suicide.”

In both 1982 and this year, Israel saw a strategic imperative to remove a Palestinian terror group posing a potent danger on its frontier. Both times, a mix of military and diplomatic pressure led to a proposal for the group to evacuate, including key involvement of Arab leaders. And as in Lebanon, the Trump plan envisions an international force coming in to ensure the terrorists comply with the agreement.

But the cases also differ in significant ways, Zisser and others noted. Hamas is the de facto sovereign in Gaza, clinging to power over two years of grueling war while continuing to hold dozens of hostages kidnapped on October 7, 2023.

In contrast, Arafat’s PLO was not the governing power in Lebanon, but rather a formidable force in exile from a land it hoped to liberate from Israeli control. Many in western Beirut were not Palestinians but Lebanese citizens who were put in harm’s way by the PLO’s fight against Israel.

“The PLO did not control Lebanon. When it left Lebanon, it did not leave its homeland,” said Dan Naor, an expert in Middle Eastern studies at Ariel University whose research focuses on Lebanon. “They were a foreign body in the area, and the people who paid the price were the citizens of Beirut who were Sunni Lebanese.”

Ksenia Svetlova, executive director of the Regional Organization for Peace, Economics and Security, added that it’s a much taller order for Hamas to leave Gaza than for the PLO to leave Beirut.

“For the PLO in Lebanon, in the end, the goal was to return to Palestine, so they left for Tunisia, but they didn’t want to go back to Lebanon, but to Gaza and the West Bank,” she said. When it comes to Hamas, she continued, “the Gazans are already there, so to leave is more significant and more painful.”

Local opposition to the PLO played a crucial role in persuading the group to evacuate, experts said.

According to Zisser, Sunni leaders in Beirut withdrew their support for the group when the fight reached their neighborhoods, a sign that Arafat’s time had run out in the city.

“The decision taken by the PLO in ‘82 had to do with the pressure put on the organization,” Zisser said. “There were Sunni leaders who supported the PLO, but when the war reached Beirut, they wanted to bring an end to the conflict. They were worried about casualties and damage, and put pressure on the PLO.”

There is no equivalent organized opposition to Hamas within Gaza, where the terror group has been in power since 2007 — though there, too, local elites are publicly pushing for the war to end.

In this case, the pressure on Hamas is coming from its international patrons, especially those such as Qatar and Turkey, which are seeking closer ties with the Trump administration. According to Yaari, the pitch being made to Hamas in 2025 is not very different from the one presented to the PLO 43 years ago.

“The Turks and the Qataris say, this is not the end of the organization,” he said. “You lose control in Gaza, you disarm. There’s life after that.”

For Arafat and the PLO, what followed was more than a decade in Tunis — until Israel allowed the group to establish itself in Ramallah as part of the 1993 Oslo Accords. For the ensuing 30-plus years, the group has remained at the helm of the West Bank-based Palestinian Authority, with broad international acceptance.

Yaari said that for Hamas, a future return to power in the West Bank is also a possibility, even if Gaza is out.

“Arafat signed Oslo and came to Ramallah,” Yaari said. Hamas’s sponsors, he continued, may be telling the group, “You’ll have our support… At the moment there are [PA] elections, you can build your strength in the West Bank.”

Yaari sees the arrival of the PLO in the West Bank as a cautionary tale for Israel, a moment when Jerusalem agreed to give legitimacy to a marginalized group based in a remote city rather than empowering locals.

Despite ushering in hopes for peace, the Oslo Accords soon gave way to years of deadly violence during the Second Intifada, which Yaari and others blame on Arafat’s refusal to abandon his terrorist ways.

A Hamas power grab in the West Bank could pose an even more potent threat to Israel, giving the group, which is sworn to Israel’s destruction, power over a piece of land that overlooks much of the country’s heartland and is home to hundreds of thousands of Israeli settlers and countless military facilities.

Hamas’s exit may also fall short of keeping Gaza from threatening Israel, analysts say, noting what happened after the PLO left Lebanon.

Just weeks after the PLO’s evacuation, Lebanese President Bashir Gemayel was assassinated in a bombing. Days later, Christian militias carried out a massacre in the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, surrounded by Israeli forces.

Backed by Iran, the new Hezbollah terror group gained power, menacing both Israel and the multinational force that came into Lebanon to help local forces assert authority.

Following the 1983 bombing of a US Marine barracks that killed nearly 300 American and French soldiers, most US and French forces left the country.

Israeli troops, unlike the international force, stayed in Lebanon for nearly two decades, controlling a strip of territory in the country’s south at the cost of hundreds of troops’ lives. The IDF withdrew in 2000 — then returned six years later to fight the Second Lebanon War.

As of now, Israeli soldiers are again in Lebanon, controlling several strategic points after another conflict Hezbollah instigated by bombing Israel following the October 7 attack. The Lebanese government is working to disarm Hezbollah after years in which a United Nations force in the south of the country, called UNIFIL, did little to prevent Hezbollah from amassing weapons.

The Trump plan, like the PLO agreement 43 years ago, also calls for an International Stabilization Force to take control of Gaza, with the IDF progressively withdrawing from the territory.

Even if Hamas does agree to leave, the analysts say it’s unlikely that the multinational force coming in to replace it will succeed — and the fight could again fall to Israel.

“An international force cannot be trusted,” Zisser said. “That’s always something we should remember in our region.”