As Abraham Accords turn 5, Israel’s willingness to use its military might becomes concern for allies

On September 15, 2020, the foreign ministers of Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates joined US President Donald Trump and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at the White House. On a balcony overlooking the South Lawn, they envisioned a region transformed.

UAE Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed predicted that the accord’s “reverberations will be reflected on the entire region.”

“For too long, the Middle East has been set back by conflict and mistrust, causing untold destruction,” lamented Bahrain’s Foreign Minister Abdullatif al-Zayani.

Exactly five years later, bin Zayed was at a different gathering — one that underscored how little the Middle East had changed. Coming together last week in Qatar in the aftermath of a failed Israeli strike on Hamas’s leaders, senior officials from nearly 60 countries — including Israel’s archenemy Iran, and the three countries that normalized relations exactly 5 years before — issued a joint statement from the summit urging “all states to take all possible legal and effective measures to prevent Israel from continuing its actions against the Palestinian people,” including “reviewing diplomatic and economic relations with it, and initiating legal proceedings against it.”

Five years after the signing of the Abraham Accords, there are undoubtedly encouraging signs of regional potential. At the same time, there is no question that ties have not met the heady expectations expressed at the White House in 2020, and that the October 7, 2023, Hamas attacks sparked processes that are placing new strains on the relationships.

“Within the larger process, there are many events that distract us, delay us, stop us,” acknowledged Eitan Naeh, Israel’s ambassador to Bahrain until last month. “You veer off the path and then you come back — but you’re heading somewhere. I think it’s quite clear where we can get to, provided we don’t run into a Hamas massacre on a Saturday and a global pandemic.”

The Abraham Accords enjoyed three relatively stable years until the Hamas invasion and massacre.

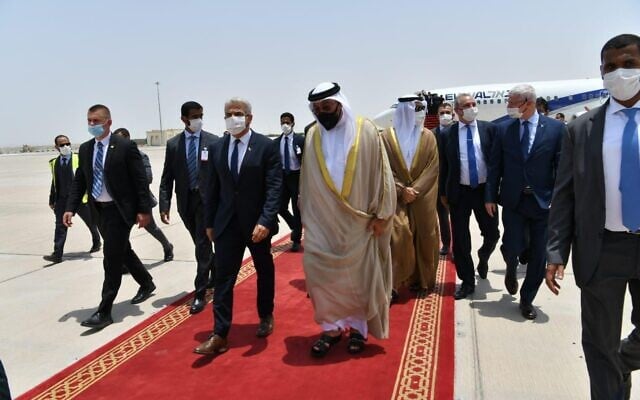

Ties moved ahead rapidly under the Naftali Bennett-Yair Lapid government, with both leaders visiting Israel’s three newest Arab allies. Lapid hosted their foreign ministers in Israel at the Negev Forum and agreements across a range of fields were signed.

“We set up the embassy, a team, and the infrastructure for relations in terms of dialogue with the leadership and with the heads of key bodies there — the Foreign Ministry, the Finance Ministry, the prime minister, the king’s palace, the security apparati,” Naeh said of his work in Bahrain. “And of course, the business community, the youth. Dialogue with media organizations, journalists.”

But even before the war, there were clear indications that the accords faced long-term challenges.

According to polling, they were consistently becoming less popular on the streets of Israel’s new allies. Washington Institute polling showed 45% of Bahrainis holding very or somewhat positive views of the agreements in November 2020. That support had steadily eroded to a paltry 20% by March 2022.

The trend was the same in the UAE. The 49% of the country that disapproved of the Abraham Accords in 2020 has grown to over two-thirds as of August 2022. And only 31% of Moroccans favored normalization at that time, according to Arab Barometer.

When Netanyahu and his hard-right allies came to power in late 2022, ties shifted noticeably downhill. The Negev Forum was not repeated, and high-level visits dried up. No senior Bahrani, Emirati or Moroccan officials visited Israel.

But aspects of the overall trend were still positive, and some relationships expanded.

Morocco, whose normalization agreement with Israel isn’t officially part of the Abraham Accords, did not experience a significant downturn under the current government. Though Rabat refused to convene the second Negev Forum over West Bank violence, Netanyahu announced Israel’s recognition of Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara in 2023, after which King Mohammed VI invited Netanyahu to his country.

Israel also appointed its first-ever military attaché to the kingdom, and the Knesset speaker and interior minister made official visits as a series of agreements were signed.

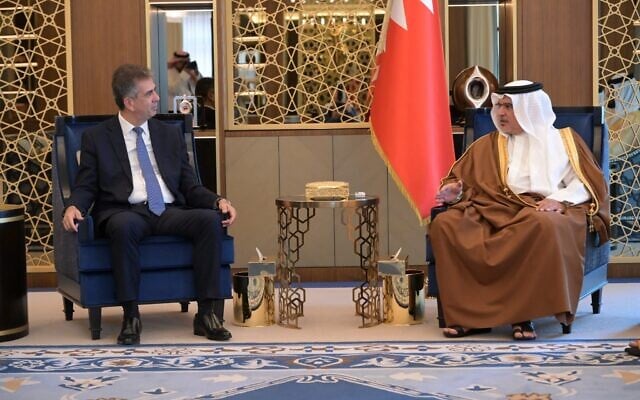

Then-foreign minister Eli Cohen’s visit to Bahrain in September 2023 was a clear indication of the trajectory of ties before the Hamas invasion one month later. He held well-publicized meetings with the prime minister, foreign minister, and finance minister, viewed a photography exhibit from young Bahrainis who had visited Israel, and had a dinner with 250 local guests, including top business leaders.

It should come as no surprise that the extended war in Gaza and in other theaters across the Middle East placed new strains on the Abraham Accords.

As before the war, there is reason for optimism, alongside warning bells.

Despite regular criticism of Israeli policies in Gaza throughout the war in official statements from its Arab partners, Jordan is the only one to officially recall its ambassador from Israel during the war. Bahrain’s ambassador Khaled Al Jalahma finished his tenure over the summer, and Manama has yet to appoint a replacement.

The Egyptian and Moroccan envoys have avoided public events and the media, but regularly fly between the countries to continue their work behind the scenes.

UAE Ambassador Mohammed Al Khaja has avoided the media but has attended high-profile events. He sat next to Isaac Herzog at the President’s official Independence Day reception in May, and embraced Jon Polin as his wife Rachel spoke about their son Hersch, who was executed by Hamas last August.

The fact that the new diplomatic relationships have survived two years of war in Gaza, and the endless stream of images of Palestinian suffering broadcast into the living rooms of the public, is evidence of how durable the relationships are.

Notably, despite the change in the tenor of the ties, Israel’s bilateral trade has grown significantly with all three countries. Compared to the same period in 2023, bilateral trade with Bahrain in the first seven months of 2024 increased by over 900%, with the UAE up 4% and Morocco up 56%, according to the Abraham Accords Peace Institute.

The same leaders who made the decision to normalize are still in power, and they are not about to admit that they made a strategic mistake in 2020

Israel is helped somewhat by the fact that its new partners are not democracies in which administrations change every few years. The same leaders who decided to normalize are still in power, and they are not about to admit that they made a strategic mistake in 2020.

“If we managed to do one thing, it was to preserve the relations — or to keep the level of dialogue as high as possible at all levels,” said Naeh.

The UAE has hosted a series of prominent Israelis during the war, but mostly opposition figures such as Lapid and Bennett.

More recently, it has hosted government officials as well. Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar was in Abu Dhabi in April to meet with his Emirati counterpart, and Deputy Foreign Minister Sharren Haskel met mid-level ministers in Abu Dhabi earlier this month.

“We’re not talking about an improvement of bilateral ties,” cautioned Moran Zaga, Gulf scholar at MIND Israel. “All the official releases that came out of the minister’s visit were about the Palestinian issue and the need to help the Palestinians. Meaning they are leveraging Israel in order to assist the Palestinians, and that’s how the statements came out.”

The Emiratis are deeply involved in all aspects of aid to Gaza, including desalination plants, aid convoys, airdrops, and field hospitals. Think tanks in the UAE have also begun discussing the country’s role in post-war Gaza.

Still, even the newfound Emirati focus on the Palestinians is an opportunity for Israel. The UAE sees a national interest in leading in Gaza and the Palestinian theater. There is an economic benefit to be had from the assistance that will flow to the Strip when fighting ends. Taking the lead on reconstruction is also a sign of the UAE’s regional leadership. And, perhaps most importantly, it allows the Emirati rulers to show the public the benefit to the Palestinians that their ties with Israel would bring.

They can be involved in all aspects of aid because of their preexisting relationship with Israel, which gives them far more access to Gaza than other regional actors.

Last week’s summit in Doha wasn’t the only indication that the long-term success of the ties isn’t guaranteed.

Israeli tourists are still flying, especially to the UAE, but there is no reciprocal flow of Arab tourists. People-to-people initiatives have ground to a halt as well during the war.

Most joint economic projects have come to a stop, and if they are happening, they are kept under the radar. While businesses involved in areas that the Arab governments prioritize — defense, food tech, cybersecurity — are moving forward with deals, others are looking elsewhere.

“If you don’t need Israel for it, why take the risk?” asked Joshua Krasna, Director of the Center for Emerging Energy Politics in the Middle East.

“The profile of the relationship is going to get even lower than it’s been up until now,” he warned.

Israel has always seen its military and intelligence might as a leading reason for Arab countries to seek ties with the Jewish state. It has led the military fight against Iranian influence in the region for years, and since October 7, Israel has enjoyed stunning success in weakening the Islamic Republic and its proxies.

“A strong Israel is an advantage for the region,” said Naeh. “I think they understand that. Who really benefits from a weak Israel?”

But Israel might now be overplaying that hand.

Israel’s Arab partners understood why it went to war in Gaza and in Lebanon, and why it carried out strikes against the Houthis in Yemen.

While they were happy to see Israel cut down Iran’s ballistic missile and nuclear program during the operation in June, Israel’s Gulf partners feared that Iran could turn on them to try to force the US to rein in Israel.

Israel’s July strikes near the Syrian presidential palace to force the new government in Damascus to protect the Druze in Suweida were also concerning, especially as the pro-Western bloc in the Middle East works to shore up the Ahmed al-Sharaa government, and while Israel was in quiet talks with Damascus.

The Qatar strike crossed the line. It was an Israeli attack on a non-enemy state, one with a decades-long history of ties with Israel.

“From their perspective, Israel is a loose cannon in the region,” said Krasna. “Israel has externalized its security considerations and now sees itself as being permitted to use force anywhere it feels its interests are threatened throughout the region, and without very much diplomatic consideration.”

“The post-Oct. 7 military campaigns — spanning Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, Yemen, and culminating in Israel’s historic direct strike on Iran — have led many Gulf officials to conclude that Israel no longer seeks mere deterrence, but rather dominance,” wrote Emirati researcher Mohammed Baharoon and Middle East Institute Alex Vatanka.

“The Iranian threat has been greatly diminished while Israel presents a new challenge of its own to regional stability, raising fundamental questions about the accords.”

The regional partners even wonder how far post-October 7 Israel is willing to go. “If Israel decides that there’s something threatening in Abu Dhabi or Dubai, who’s to prevent them from acting there?” asked Krasna.

And there is a growing concern that Israel’s Arab partners will pay the price for Israel’s strikes in Iran and across the Middle East.

The possibility that Israel could annex parts of the West Bank in response to this week’s wave of Western recognition of a Palestinian state is a further reason for regional leaders to worry — not only about them being forced to take some action against Israel, but also about the ability of Israel’s leaders to overcome the tactical concerns of coalition politics in order to advance a vision of a stable and reformed Middle East. Israel made peace with autocratic kingdoms and emirates, and their tolerance for the demands of messy democratic politics is limited.

Despite all the challenges, however, Israeli diplomats are confident that they can move things forward again… once the war ends.

“Foundations have been laid,” said Naeh. “We will, of course, need to nurture this anew. We’ll need to rebuild. We’ll need patience.”

—