Researchers have deciphered a tiny third-century Christian silver scroll that was found rolled up inside an amulet, at a Roman burial site in Frankfurt, Germany. The find was hailed by the Frankfurt municipality as “the oldest Christian testimony found north of the Alps,” in a recent announcement.

The scroll was discovered in 2018 during excavations in the “Heilmannstraße” cemetery in the city, a site with hundreds of Roman-era graves. The area was once part of Nida, a Roman border town that eventually was abandoned. The particular grave that held the scroll was dated to 230-270 CE, predating other Christian texts in the region by at least 50 years, the press release said.

The scroll, made of a thin silver foil, was found rolled up and inserted into a 3.5-cm-long silver amulet, which was likely designed to be worn around the neck. The grave also held various goods, including an incense burner and a clay jug.

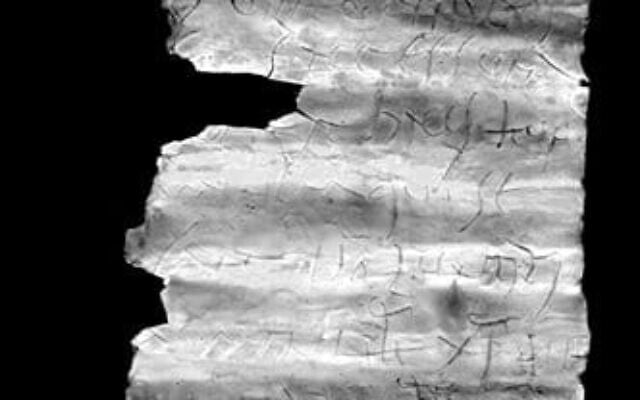

Because the scroll was too delicate to unroll, and because X-ray analysis was unable to reveal the contents except to confirm that there were indeed words written on the scroll, the artifact “was examined using a state-of-the-art computer tomograph” at the Leibniz Center for Archaeology in Mainz, Germany, where researchers were able to conduct multiple high-resolution scans of the scroll and create an accurate model, a kind of “digital unrolling,” the release said.

Prof. Markus Scholz of Frankfurt’s Goethe University then examined and translated, with the help of other experts, the 18 lines of Latin that were found to be on the scroll.

Finding such a scroll written entirely in Latin is “unusual for the time,” Scholz said. “Normally, such inscriptions on amulets were written in Greek or Hebrew.”

It is also very unusual that “the amulet is purely Christian,” he added.

“Up until the fifth century, a mixture of different faiths can always be expected in precious metal amulets of this type. Often elements from Judaism or pagan influences can still be found,” but in this case, there were none, he said.

The researchers provided a translation of the protective prayer discovered in the scroll and noted that some sections were still indecipherable or the interpretation was uncertain, indicated by question marks:

(In the name?) of St. Titus.

Holy, holy, holy!

In the name of Jesus Christ, Son of God!

The lord of the world

resists to the best of his [ability?]

all seizures(?)/setbacks(?).

The god(?) grants well-being

Admission.

This rescue device(?) protects

the person who

surrenders to the will

of the Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God,

since before Jesus Christ

bend all knees: the heavenly ones,

the earthly and

the subterranean, and every tongue

confess (to Jesus Christ).

An initial analysis of the text revealed some significant aspects, including the formulation of “holy, holy, holy,” a phrase drawn Jewish liturgy but “not actually known in the Christian liturgy until the 4th century CE,” the researchers said.

The reference to St. Titus, an early missionary and disciple of the Apostle Paul, is also unusual, and the connection to Paul is reinforced by the last lines of the scroll, which are “an almost literal quotation from Paul’s so-called Christ hymn from his letter to the Philippians,” the researchers said.

The bearer of the silver amulet “was clearly a devout Christian,” which for the time and place “is absolutely extraordinary,” the notice said. The Frankfurt area, north of the Alps in central Europe, is quite far from the eastern Mediterranean and Levantine centers of early Christianity, and the presence of the amulet there is a sign of the “cultural and religious diversity” of the area, the researchers said.

Yet, the presence of such an amulet “does not necessarily mean that there was a big Christian community there, since such amulets are easily transportable,” said Prof. Gideon Bohak, of the Department of Jewish Philosophy and Talmud at Tel Aviv University, in a message to The Times of Israel.

“Assuming that the reading and the dating are correct, we would have here an early Christian amulet, written in Latin, and found in a remote town on the northern edges of the Roman Empire,” he said, noting that it was necessary to “wait for the full academic publication” in order to “check their interpretation of the find.”

A similar artifact was found several years ago in Austria on a sheet encased in a child’s gold amulet, “on which was written Shema Israel (the entire verse) in Hebrew, but in Greek letters… This is a Jewish amulet, also found in a remote corner of the Roman Empire, and also dating to the third century, so I think this is quite an analogous find,” Bohak said.

At the time the Frankfurt amulet was dated, the mid-third century CE, Christianity was outlawed in the Roman Empire and practitioners were persecuted, a situation that was altered by Emperor Constantine in 313 CE, with his Edict of Milan, which recognized Christianity as an official religion.

In 325 CE, the Council of Nicea distilled the diverse strains of early Christianity into a single set of beliefs, and in 380 CE, with the Edict of Thessaloniki, that form of Christianity became the official state religion of the Roman Empire.

Artifacts of a similar type, either prayers for protection inscribed on gold or silver or curses written on lead and then inserted into a protective amulet or case, were common in the ancient world. A similar silver amulet was recently discovered in Bulgaria, and several years ago, a scroll from the fifth century found in Turkey was discovered to contain a curse against a chariot racer, written in Aramaic with Hebrew letters.