At the beginning of July, the Hamas-run religious affairs ministry in Gaza issued a rare statement declaring that burial space in the Strip has been exhausted.

According to the statement, the shortage had been caused by “the destruction of cemeteries during the war” as well as evacuation orders which have forced more and more Gazans away from urban areas, leaving them without access to traditional burial spaces near their homes.

And then there is the sheer number needing burial, with over 58,000 dead in the last 21 months of war, if unverified Hamas-provided tolls are to be believed.

“The old cemeteries in the Gaza Strip are full. There’s no room to bury any more bodies,” a Gaza resident who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons told The Times of Israel in a WhatsApp chat. “This started in the first months of the war and has gotten worse as the death toll has risen. Here in Gaza, there’s no safe place to live and no space to bury the dead.”

The reported shortage is just the latest humanitarian crisis to beleaguer the Strip, which has been beset by war, displacement, and hunger since Gaza’s Hamas rulers embarked on a campaign of destruction inside Israel on October 7, 2023, bringing death and carnage to the Strip.

While the grave shortage has received less international attention than dwindling supplies of fuel and food, it nevertheless has had a profound impact on daily life in the Strip, reflecting the worsening conditions for Gazans trying to meet their daily needs with dignity. Exacerbating the situation is the Islamic prohibition on cremation, making burial the only viable option for the vast majority of Gazans.

Unlike other critical needs, the issue of burial space has yet to be addressed by humanitarian groups such as the Red Cross or organizations operating under the UN in the strip.

“Gaza is extremely crowded, and now large parts of it are off-limits,” the Gaza resident said. “Where are we supposed to bury the dead?”

The death toll in Gaza has been a matter of dispute since the earliest days of the war, which Israel launched after Hamas massacred some 1,200 Israelis and kidnapped 251, the majority of them civilians. Israel launched a massive air campaign that same day, followed by a ground invasion of Gaza several weeks later.

As of July 20, according to Gaza’s Hamas-run health ministry, 58,895 people have been killed directly by Israeli military action since the war began, not including deaths from hunger or disease or natural death. Hamas does not break down the toll by how many are fighters and how many are civilians, but it has released detailed lists of names, ages, birthdates, and Palestinian ID numbers of the dead, showing that many are women and children.

There has been no outside verification of the toll, though in previous military operations in Gaza, the final death toll reported by Hamas tended to be relatively close to Israeli estimates.

Those earlier operations, however, were far shorter and took place when Gaza’s health infrastructure was functioning more effectively.

Throughout the war, several studies have pointed to inconsistencies, duplicates, and irregularities in the published casualty lists, casting doubt on the reported death toll.

However, other analyses have suggested the opposite — that the official count might underrepresent the actual number of dead, given the chaos of war, the collapse of recordkeeping systems, and the likelihood that many bodies remain buried under rubble and are registered as missing rather than dead.

In the last year, Israel has not formally addressed the overall number of Palestinian fatalities, and its last estimate for the number of combatants killed in the Strip was in January, when it said it believed approximately 20,000 Hamas and allied fighters were among the dead, along with 1,600 killed inside Israel on October 7.

But even if the exact numbers remain disputed, there seems little doubt that many in the Strip are dead, with Gazans increasingly saying they are running out of places to put them.

A major factor contributing to the shortage of burial space is Israel’s military control over large swaths of Gaza, where civilians have been forced out by sweeping evacuation orders.

On July 16, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported that 86 percent of Gaza’s territory was under Israeli military control or designated as an evacuation zone since March 18, when fighting resumed following a two-month ceasefire.

In early July, the Ynet news site reported that military leaders had informed Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s security cabinet that it expected to complete its occupation of approximately 75% of the Strip within weeks.

The orders have left Gazans without access to their homes or their graveyards.

“A lot of cemeteries are located in areas under Israeli control and are now considered ‘red zones’ — no-go areas for civilians,” the Gaza resident said.

Many of Gaza’s cemeteries are located on the eastern side of the Strip, where there is more open land, a resident of Gaza City told the Palestinian Authority’s official news agency in a video report.

But due to its proximity to the Israeli border, much of the eastern side of the Strip has also remained under Israeli control for most of the war, with only a brief reprieve during the ceasefire in January 2025. That forced Gazans to use other cemeteries, which quickly filled beyond capacity.

Since the early months of the war, videos have circulated online showing mass graves dug in open areas outside official cemeteries. As Israel expands its control and restricts movement, even this option is becoming harder to access.

Most Gazan civilians have been told to evacuate to the al-Mawasi area in the southwestern part of the Strip, which has been transformed into a vast tent city. The area, the former location of an Israeli settlement bloc, has no existing cemetery, and no space there has been designated as a burial ground.

Some media outlets in Gaza attribute the burial crisis in part to the destruction of cemeteries by the IDF.

The IDF spokesperson told the Times of Israel that the army only directs strikes at military targets.

“Since October 7, 2023, terrorist organizations in the Gaza Strip, led by the Hamas terrorist organization, have been systematically operating from within civilian environments, in serious violation of the laws of warfare, and exploiting civilian sites and infrastructure for terrorist activity, including schools, hospitals, and cemeteries,” the spokesperson said. “Therefore, the IDF is compelled to operate in these areas while taking measures, as much as possible, to minimize collateral damage to civilians and sensitive sites.”

During the war, the military published evidence indicating that Hamas used cemeteries in the Gaza Strip for terrorist purposes, resulting in some military operations taking place in graveyards.

For example, in January 2024, the IDF revealed a Hamas tunnel route beneath a cemetery in Bani Suheila, in the Khan Younis area. According to the IDF, this tunnel was part of an extensive underground maze dug by the Hamas terrorist organization. It stretched approximately one kilometer, included several compartments, and reached a depth of about 20 meters (65 feet).

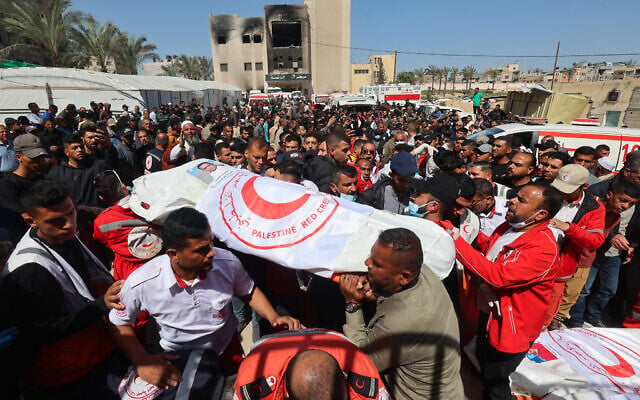

On June 30, the morgue at Nasser Hospital in Khan Younis declared it had no remaining space in its on-site cemetery — an improvised graveyard believed to have been established during the war. Over the past year, videos have shown burials occurring in hospital courtyards due to ongoing hostilities that made it too dangerous to take bodies elsewhere.

A doctor at Nasser Hospital, who requested anonymity, confirmed in a phone call with The Times of Israel that a burial space crisis exists. However, he emphasized that the hospital bears no responsibility for the bodies.

“Hospitals are not responsible for the dead. The families take their relatives and bury them themselves,” he said.

Increasingly, though, many families are not taking the bodies at all.

In recent weeks, videos have proliferated online showing corpses piling up in hospital morgues — a pattern also seen in earlier stages of the war.

One solution now being adopted, according to reports in Gaza, is the practice of “double burial” — placing multiple victims in a single grave, or reopening old ones.

A Gaza City resident, interviewed by the Palestinian Authority’s official news agency, said he buried his three children in a single grave due to the shortage.

“The cemeteries we can still reach are full,” said the Gaza resident who spoke to The Times of Israel. “Sometimes we have no choice but to open old graves or bury several people in the same one.”

Even before the war, Gaza faced a shortage of burial space. In 2002, a cemetery caretaker told local media he had to turn families away because there was no room left.

Home to a pre-war population of around 2 million living on 365 square kilometers (141 square miles), Gaza is often described as among the densest places on earth, with roughly 5,600 people per square kilometer.

But the problem goes beyond simple land scarcity. Gaza’s density, or even that of Gaza City, is far lower than many other places around the world, including the Philippines, Nepal, France, Belgium, and even Israel. Rather, what makes Gaza feel so crowded is poor urban planning.

Even before the war, economic hardships made it challenging to build high-rise housing. The Hamas government invested little in building to address the density, and chronic shortages of water, electricity, and employment stifled the conditions needed for redevelopment. Critics of Hamas say the terror group poured concrete into its vast underground tunnel network rather than using it to build new residential towers.

Politics also played a role. Gaza is home to 10 refugee camps which have remained little changed since they were created to house Palestinians displaced during Israel’s War of Independence in 1948.

Home to their descendants, the now-teeming camps are still viewed as “temporary” by a Palestinian society eager to see those living there return to their ancestors’ former homes inside present-day Israel.

Rather than redevelop the camps in a sustainable way for their growing populations, which many would view as an admission of settling in, the camps have dealt with crowding in an ad hoc way, spreading living space haphazardly over every bit of open land, and leaving no room for the inevitable end.