Zainab Mustarah once spent her days running an events planning firm in Beirut. But for the last year, she has been in and out of surgery to save the remnants of her right hand and both eyes, maimed when Israel detonated booby-trapped pagers in Lebanon.

On September 17, 2024, thousands of pagers carried by members of Lebanese terror group Hezbollah exploded simultaneously, followed the next day by booby-trapped walkie-talkies.

Thirty-nine people were killed and more than 3,400 wounded, including children and other civilians who were near the devices when they blew up but were not members of the Iran-backed group, according to Lebanese tolls that did not differentiate between civilians and members of the terror group.

While it is not known how many Hezbollah members were injured, a Hezbollah official told Reuters a week later that the attacks put 1,500 of the group’s fighters out of commission due to their injuries, with many having been blinded or had their hands blown off.

Mustarah, now 27, was one of the wounded. She told Reuters she was working from home when the pager, which belonged to a relative, beeped as if receiving a message. It exploded without her touching it, leaving her conscious but with severe wounds to her face and hand.

Media reports have detailed that the pagers and sent message were designed in a way that required operators to hold the device with both hands in order to press two buttons simultaneously, setting off the blast. However, the pagers were also designed to explode anyway, a short time after the messages were sent.

Her last year has been a flurry of 14 operations, including in Iran, with seven cosmetic reconstruction surgeries left to go. She lost the fingers on her right hand and 90 percent of her sight.

“I can no longer continue with interior design because my vision is 10 percent. God willing, next year we will see which university majors will suit my wounds, so I can continue,” she said.

The exploding pagers and walkie-talkies were a decisive development in an escalating conflict between Israel and Hezbollah that began in the wake of the devastating Hamas-led invasion of Israel on October 7, 2023. Hezbollah started firing across the northern border in support of Hamas, drawing Israeli retaliation. The fighting eventually escalated into a full-blown war that left the terror group badly weakened and swaths of Lebanon in ruins.

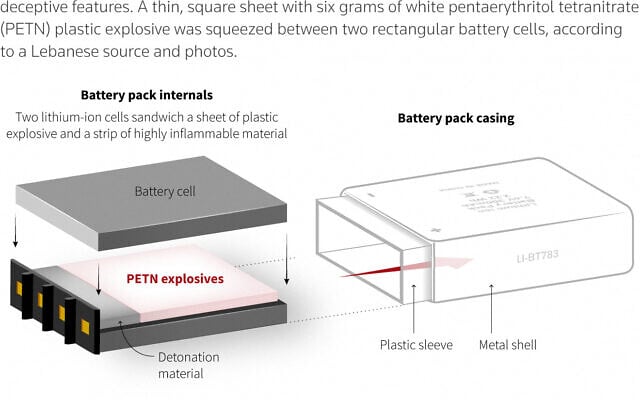

A Reuters investigation found that Israel had concealed a small but potent charge of plastic explosive and a detonator into thousands of pagers procured by the group.

They were carried by fighters, but also by members of Hezbollah’s social services branches and medical services.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Volker Türk, said at the time that the explosions were “shocking, and their impact on civilians unacceptable.”

He said simultaneously targeting thousands of people without knowing precisely who was in possession of the targeted devices, or where they were, “violates international human rights law and, to the extent applicable, international humanitarian law.”

Mohammed Nasser al-Din, 34, was the director of the medical equipment and engineering department at Al-Rasoul Al-Aazam Hospital, a Hezbollah-affiliated facility, at the time of the pager blasts. He said he had a pager to be easily reached for any maintenance needs there.

At the hospital on September 17 last year, he spoke by phone with his wife to check in on their son’s first day back at school.

Moments later, his pager exploded.

The blast cost him his left eye and left fingers and lodged shrapnel in his skull. He lay in a coma for two weeks and is still undergoing surgeries to his face.

He woke to learn of the killing of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in a barrage of Israeli strikes on Beirut’s southern suburbs, a turning point for the group and its supporters.

But Nasser al-Din did not shed a tear — until his son saw the state he was in.

“The distress I felt was over how my son could accept that my condition was like this,” he said.

Elias Jrade, a Lebanese member of parliament and eye surgeon who conducted dozens of operations on those affected, said that some of the cases would have to receive lifelong treatment.

“There were children and women who would ask, what happened to us? And you can’t answer them,” he told Reuters.