DAMASCUS, Syria — In a different world, it might be a four-hour drive from my home to the hotel where I’ll be sleeping tonight. Jerusalem to Damascus is less than 200 miles as the crow flies. But it’s taken me three flights to get here — from Tel Aviv to Athens, then to Istanbul (there are no direct flights between Israel and Turkey anymore), and finally, now, from Istanbul to Damascus.

As the plane nears Damascus International Airport — bombed three times by Israel in late 2023, amid cross-border skirmishes in the first weeks after the Hamas massacre — I try in vain to spy the runway in the flat, beige, sandy landscape.

There are just a handful of planes on the tarmac as we land — Air Dubai, Jazeera, another two from Turkish Airlines. I walk down the airstairs where two buses are waiting to take passengers to the terminal, past a small fleet of black BMWs, and get on the bus, but one of the members of our group calls me back. The BMWs, it turns out, are for the nine of us.

With handshakes and smiles, we’re ushered into the convoy, and whisked around to the back of the terminal. We are led into a wood-paneled VIP room, elegantly chandeliered, with a three-red-starred flag of the Syrian Arab Republic in one corner and a “Welcome to Syria” banner alongside it. Two comfortable chairs face into the room, with other chairs all around — the kind of seating arrangement where a leader hosts his honored guest, and their delegations pay rapt attention.

We are invited to sit and offered water and coffee, as two gentlemen collect our passports and disappear to process our entry, and Rasha Ghannam from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and her elegantly suited colleague from the protocol department tell us that we are most welcome in Syria.

It is, as much of the coming 48 hours will prove to be, a deeply surreal experience to be an Israeli, accompanying a very obviously Jewish group, warmly greeted on arrival in the neighboring enemy state of Syria.

The only member of this group to be Israeli, living in Israel, and a journalist, I am here because Asher Lopatin, a modern Orthodox rabbi from Michigan, has put together a group for “a goodwill trip from the Jewish community, mostly the American Jewish community, to help build relations between Syria and American Jews, and other Jews, and to influence both the United States and Israel to come to a closer relationship with the new Syrian government and to help the Syrian people.”

Among the participants is Lawrence Schiffman, professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at New York University and director of the Global Institute for Advanced Research in Jewish Studies; Carl Gershman, the founding president of the National Endowment for Democracy and a former US representative to the UN Security Council; and Mendy Chitrik, the Safed-born rabbi of Turkey’s Ashkenazi community. The trip is being coordinated from Syria by a Syrian-born American named Joe Jajati, the grandson of a former leader of Syria’s Jewish community who has established the Syrian Mosaic Foundation, which aims “to unite Syrians and global supporters in celebrating our diversity and building a brighter future.”

And most importantly, the visit has been formally approved by the Syrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, now under the authority of Syria’s new President Ahmed al-Sharaa, a veteran jihadist who until last December had a $10 million US bounty on his head for terrorism, and whose rebel forces ousted the regime of Bashar al-Assad on December 8, 2024.

A member of our group had an Israeli visa in his US passport; it spooked the Turkish Airlines official as we prepared to board for Damascus at Istanbul Airport, but the Syrian officials had no issues with it

I was delighted when Lopatin invited me to tag along, though I didn’t absolutely share his confidence that the Syrian leadership would agree to have the editor of The Times of Israel, as stated in the bio he submitted on my behalf, join the group, even entering on my British rather than my Israeli passport. But it turned out, as it often does with Lopatin, that his optimism was well-founded. Another member of our group had an Israeli visa in his US passport; it spooked the Turkish Airlines official as we prepared to board for Damascus at Istanbul Airport, but the Syrian officials had no issues with it.

(I should stress that I am not the first Israeli journalist to enter Syria of late, and nor is this trip remotely an act of bravery. The immensely courageous war correspondent Ithai Enghel made his way to Syria as the Assad regime was collapsing, and found his way into military bases, a prison, and a hidden section of the Iranian Embassy, producing extraordinary footage for Channel 12’s Uvda investigative program.)

“How is it,” I ask Ghannam, in these first few minutes inside an enemy land I never expected to see, “that we are here” — an overtly Jewish group including Orthodox rabbis and scholars — “and that I am here.”

She makes it sound entirely matter of fact: Lopatin, who first visited Syria early this year, “submitted a request for a friendship visit. We looked at the goals. Syria is open to different religions and cultures. So we said yes.”

I hadn’t known what to expect at all from the trip, in terms of how nervous we’d feel, how wary to be. I’d switched out my iPhone screensaver pic that shows some of my children in IDF uniform. I’d taken shekel banknotes out of my wallet.

I’ve been in Jordan and Egypt, peace partners, and felt hostility in interactions with officialdom. (As I edit these very words, two Israelis have just been killed on the Jordan border.) Jordan routinely confiscates tefillin from Jews crossing in and out. We were entering an enemy state, and Lopatin had suggested we bring tefillin and siddurim, assuring us this would be fine. And here he is in the VIP arrival room, kippa on head, and so far it is.

We leave the airport in a convoy of turquoise blue SUVS, arranged by the redoubtable Jajati, with an escort of at least four security vehicles.

The signs on the initially empty two-lane road out of the airport, largely barren territory at either side, point to crazy destinations for an Israeli: “Lebanon” (straight ahead); “Iraq” (turn right).

We pass what looks like a refugee camp as we near Damascus, the traffic builds, and the sides of the road are populated with people selling mattresses, old furniture, plastic kitchen utensils, and large numbers of new children’s bikes.

Now we enter a war zone. This is Jobar, our first destination, a former rebel stronghold that our driver tells us was bombed and shelled by Assad for 11 years: Street after street after street is filled with the gray skeletons of buildings, broken teeth gaping up from endless mounds of rubble. “This is cleaned up,” the driver says as the convoy moves deeper into the remains, by which he means that enough roads have been cleared for cars to get through.

Our two days in Syria’s capital will be spent in a dizzying sequence of visits to Jewish sites and meetings with government officials. This stop is from the first category. We have come here because Jews lived in this neighborhood for hundreds of years, until 1995, and there is a synagogue Lopatin wants to visit.

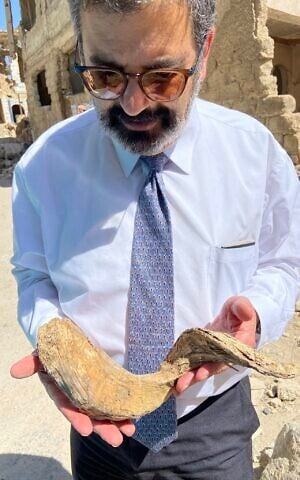

When we arrive, there is nothing or almost nothing that hints of this. When he was here a few months ago, Lopatin said there was a last arch of the shul still standing. That too has gone. Would-be thieves have dug tunnels down through the rubble in the likely vain hope of finding valuable artifacts. Lopatin does come across what looks very like a shofar, but might just be a decaying, curling tube of wood.

“This was the Eliyahu Hanavi Synagogue,” Jajati tells me, Syria’s oldest. It was built above a cave believed to have been used by the prophet Elijah in hiding, but there is no trace of that cave now, either. The synagogue is believed to date back to 720 BCE, and survived through to 2014, when it was hit by mortar shells, further destroyed by fire, and looted. Now, there is nothing.

We make our way out of the area, but, remarkably, this will not be our only encounter with the ghost of the Eliyahu Hanavi Synagogue. The next one will be slightly more positive.

Our next stop is at Damascus’s Jewish cemetery — graves going back hundreds of years, and some just added.

Syria’s Jewish community dates back to the time of King David but is now on the very brink of extinction — from perhaps 100,000 people a century ago, to 15,000 by the late 1940s, to almost none since the 1990s. There seem to be six Jews still living in Syria — four men and two women — two of whom we meet in the next few days. Several others had died in recent years; Chitrik points out some of their graves. He led a funeral ceremony over Zoom for one of them from his home in Turkey during the COVID era.

Pride of place at the cemetery is taken by the tomb of Rabbi Hayyim Vital, leading disciple of the father of contemporary Kabbalah, Isaac Luria, who was buried here in 1620. On his previous visit, Lopatin came across the gravestone of Vital’s wife Naomi, and he’s got the idea that we can maybe carry it the several hundred yards from its current resting place and into the tomb of her husband. As Lopatin disappears into the distance to re-find Naomi’s headstone, a local woman, a member of the family that lives inside the cemetery walls next to the building of the hevra kadisha (Jewish burial society), appears and offers us much-needed water.

When we follow Lopatin out to Naomi Vital’s headstone, it’s pretty evident that nobody’s going to be lifting it — and certainly not our not-entirely-youthful crew. The rabbi instead recites the “El Malei Rahamim” prayer for her soul.

Behind him as he intones the prayer is a large mound of gravestones, apparently removed when the adjacent main road was built and piled up here at random. At least the highway builders of the Assad era chose not to pave over the entire cemetery.

We then return to Haim Vital’s tomb and gather, along with a few of Jajati’s visiting friends who have appeared, for the first minyan over the late kabbalist’s grave in what is surely many a year.

Members of the government’s security team, the protocol department and the drivers watch some of this unfolding. We get quite friendly with them over the coming two days, as far as our general lack of a common language allows.

Without warning, we now find ourselves being driven a considerable distance around what appears to be much of Damascus, the convoy cutting in and out of heavy traffic in an endless cacophony of horns.

Among the sights, we pass the Defense Ministry building in the city center — bombed by the Israeli Air Force just two months ago, as Israel pressed the Syrian government to withdraw its forces from the Druze heartland of Sweida in the south — with the damage plain to see.

We pull up at what turns out to be a police station. Here, in an upstairs room, leaning up against the wall of the captain’s office, are two bronze doors of a synagogue — which were stolen last week, reported stolen immediately by Jajati, and recovered the same day by the captain and his men.

It is becoming quite evident, and we will hear a lot more about this in our meetings with officials tomorrow, that the new Syrian leadership is interested in cultivating good relations with the Jews of Syria who now live abroad, notably in Brooklyn — encouraging them to consider returning, to be part of the country’s intended revival, to serve as an emblem of a new, tolerant Syrian era, to symbolize a Syria that should be invested in and supported.

Thus, in this clearly well-organized stop on our trip, a Syrian TV crew is on hand to film the visiting Jewish group’s pleasure at the rapid recovery of the purloined portals, and to interview Lopatin, who praises the police’s exceptional efficiency.

Jajati tells me the doors were stolen from the Menarsha synagogue, and that there is no way they can be securely returned there, and so they will stay at the police station for the time being.

We now take a 10-minute walk through the streets of Damascus, past bakeries and fruit stalls and garages, with a handful of security people and armed soldiers nearby. Led by Lopatin, carrying his tefillin bag, we are a little group of Jews walking through what used to be a fairly Jewish neighborhood and attracting a mixture of mildly curious and smiling glances — taking a literal few first steps, perhaps, to renormalizing Jewishness in an area where it has all but disappeared.

Our destination is the Elfaranje Synagogue, built by immigrants fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. Entering is not straightforward. The shul was in routine use when there was a community here, but there has been no minyan for at least a decade and there appears to have been some confusion about who holds the keys to the multiple locks and chains that secure it.

After a lot of trial and error, all the right keys are found and we enter the building, accompanied by one of those last six Damascene Jews, Bachar Simantov, a charismatic silver-haired figure of sparkling teeth and unknowable age who assures me that he is 35 years old and that, although his family is in Israel and the US, he will stay in Syria for the rest of his days.

For all of us visitors, I think, this is one of the most moving parts of our stay — reviving prayer, davening with a minyan, in a very old synagogue that is nonetheless completely intact; it feels like the former Jewish worshipers have just left the building.

Chitrik leads the service. Lopatin opens the ark and takes out a Sefer Torah for the brief Monday reading, and we sing “VeZot HaTorah” — and this is the Torah. Jajati performs Hagba, displaying the scroll. People are called to the bima. The scroll is returned. All watched by the protocol and security personnel.

The decorations on the innermost set of doors include two tablets bearing the first words of the Ten Commandments. Blessed by the presence as translator of one of Jajati’s colleagues, a much-traveled young Muslim man who speaks native Arabic and English, we establish that Islam sets out similar principles. I talk one of the protocol officers through the commandments as inscribed on the doors, and he nods in recognition.

It’s late afternoon now, and we’re all pretty exhausted.

We are driven to our hotel, in Damascus’s Old City — a building formerly owned by Jajati’s father, Faraj, the home where Joseph grew up. You can still see the faint marks where the mezuzah used to be affixed to the doorpost.

Israelis used to speak about the day when we’d be “eating hummus in Damascus” as being emblematic of a longed-for era of peace. Now, we’re eating hummus in Damascus, and it’s even kosher

Chitrik is supervising a kosher dinner, having brought in frozen meat in his suitcase and prepared the kitchen as required. He’s also sourced local hummus untainted by any ingredients or implements that would render it non-kosher.

Israelis used to speak about the day when we’d be “eating hummus in Damascus” as being emblematic of a longed-for era of peace. Now, we’re eating hummus in Damascus, and it’s even kosher, says Chitrik.

While the food is cooked, a few of us, in twos and threes, go for a walk to the main souk, just around the corner. A security guard accompanies some of our number, but others go out unescorted. The day’s official itinerary is evidently completed now, and our security is apparently not thought to be at risk.

I stroll on my own through some of the streets and alleys — not looking particularly unusual, and thus attracting zero attention. I peer into an antiques store where I’d seen Jajati and two others of our group chatting happily a little earlier, and owner Mohammad insists on walking me to an adjacent change place. Absurdly, it will turn out, I decide to change $100, and am rewarded with three bricks of notes in 5,000 and 2,000 denominations.

The 2,000-pound notes still bear the face of Bashar al-Assad, reputedly hiding out in Moscow but still ever-present in the shattered Syria he left behind. (In contrast to the Assad dynasty, I see no cult of Sharaa in our brief visit, no massive posters with his features hanging from buildings.)

Back in the change place, they hand over my 1.34 million Syrian pounds. The bricks of cash are far too large to stuff into my various pants pockets. They offer me a plastic bag.

Mohammad says the pound has lost almost two-thirds of its value since the civil war began in 2011. “So, things have gradually become worse economically?” I ask him. “Yes, but the country is better now,” he replies.

Later, I run into Lopitan, kippa on head as ever, in the souk. He is looking for some “I love Syria” hats for his family. No luck. They have plenty with the republic’s eagle symbol, but those look a little, well, military.

We buy ice cream instead. I peel off three 2,000-pound notes from my vast pile.

Tuesday is our meet-the-ministers day, and it begins at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

We drive in our fleet of turquoise taxis to an area that combines new and under-construction high-quality residential high-rises and large, grand, white stone government offices. There are 10 high-rises nearing completion in the area immediately around the ministry building, a controlled frenzy of rebuilding.

Received with smiles and a fairly perfunctory security check, we wait in a spacious ground-floor room for Qutaiba Idlbi, a former senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs and today the director of American Affairs at the ministry.

Tall, well-dressed and a perfect English-speaker, he proves to be by far the most outspoken of the senior officials with whom we will meet. And he reserves his heaviest criticism for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the Israeli government’s dealings with the new Syrian leadership.

Idlbi opens by saying that it is important to help Syria reconnect with its people, including its Jews. He notes lightly that ancestry.com has informed him that he himself has “14% Ashkenazi blood.” The room laughs.

He calls December 8, 2024, “the start of a new era for Syria — building bridges internally and externally” and notes that the Jewish community well knows about “the fractures” of previous decades that forced its near-complete departure.

Lopatin stresses the goodwill nature of the group’s visit, Chitrik notes that Jews have been in Syria for thousands of years, and Idlbi responds that the new leadership wants those abroad to know that they will be welcomed if they want to come home. He also says the ministry has just appointed a young official, Hamad Kara Ali, with whom we meet later, to work on matters that affect the Jewish community, including disputes relating to property and other assets lost due to persecution.

“We are trying to build a bridge” to Syrian Jews in the Diaspora, Idlbi says, and to help them come back should they so desire. He says officials have met with Syrian Jews in New York. (There are rumors that Sharaa may hold such meetings during his imminent visit for the UN General Assembly.

He says Syria is trying to build a foreign policy based on “relationships and cooperation and shared interests, and management of disagreements rather than conflict.”

We do have [only] a slim window… In most cases where you have a civil war, as soon as you make a transition, you fall back into civil war

He believes, and we hear this from all the ministers we meet, that “stability is the desire of the Syrian people,” although “there are some attempts” by members and supporters of the Assad regime to prevent this. The fact is, he says, that the Syrian people “have the ability to start a civil war” — or rather restart one — “if they want to. They don’t want to.”

Nonetheless, he stresses, “we do have [only] a slim window… In most cases where you have a civil war, as soon as you make a transition, you fall back into civil war. Syria is one of the few cases where [that has not happened]; we have survived.”

This is where he starts to focus on Israel — of his own volition and, subsequently, in response to questions from the group and this reporter.

“I separate between what Netanyahu is thinking and doing,” Idlbi says, “and the Israeli people and the Jewish people as a whole.”

Generally, he assesses that “Netanyahu is leading Israel into a period of international isolation.” Specifically, he accuses the prime minister of trying to utilize this summer’s deadly fighting in Sweida “to create another war,” and charges that while “many people in Israel want to turn the page, that is not shared by Netanyahu.”

While Israel claims it is protecting the Druze, honoring a historical commitment to the Druze on the Israeli side of the border, he counters that the IDF targeted the new government’s security forces in Sweida as they tried to restore calm, rather than those who were engaged in the sectarian violence. “Don’t target us,” he urges.

The Israeli government has also highlighted its imperative to ensure that Israel’s northern border is not threatened by instability in southern Syria and a potential power vacuum that Iran and others would seek to exploit. Idlbi is thoroughly unpersuaded. “Since December 8, the Netanyahu government has been the main threat to Syria,” he charges, citing 900 attacks by the Israeli army inside Syria and asserting “zero threats from Syria to Israel.”

Idlbi is adamant that “we want to establish security over the south… We want to see if we can have an arrangement where people feel secure on both sides of the border.”

He says that “we understand the October 7 trauma for the Israeli people” and speaks of ultimately seeking “a peace deal based on the 1967 borders.”

But this will all take time, he says. For now, he claims that “in our conversations with Israeli officials” it seems evident that “they don’t want a stable Syria.” Rather, he asserts, Netanyahu appears to want a reality in the south — near the Israeli border — where the Syrian government cannot exercise control.

This is a mistake from Israel’s point of view, Idlbi argues. “We were lucky that we were able to push Iran and Hezbollah out of Syria on December 8… But Iran is ready to step in,” he warns. “Hezbollah is ready to step in.” And thus, Netanyahu risks “creating the seeds for the next confrontation.”

He also says Israel is seeking a Druze cross-border corridor, and this is something Syria cannot accept.

The new government, he says, is determined to “turn the page on non-state actors… There are 1.5 to 2 million fighters who have been engaged in fighting. That is not an easy situation to control.” And therefore, he argues, “Anyone who is realistic enough can see that a stable Syria is actually in the interest first and foremost of Israel.”

As we sit in the ministry, Israeli-Syrian negotiations are in full sway, with the US administration reportedly seeking to finalize a new security agreement even before next week’s United Nations General Assembly. Based on separation of forces agreements from half a century ago, this could reportedly provide specifics, as does the Israel-Egypt peace treaty, on where and how Syrian forces would be permitted to deploy in and near areas bordering Israel. By the time we headed home from Syria the next day, Sharaa was stating that the talks could yield results “in the coming days.”

Idlbi is dismissive of the rumors that Sharaa might meet with Netanyahu on the sidelines of the General Assembly. “There is no plan for a meeting at the UN,” he says.

He’s probably right. Probably. But things are plainly moving fast behind the scenes.

When we return to the Foreign Ministry later Tuesday to meet Hamad Kara Ali, the newly appointed point man for issues of Jewish concern, Jajati praises the police for moving so fast to return the stolen doors of the Menarsha Synagogue, and highlights the need for more security at Jewish sites.

Chitrik raises the case of Salim Jamous, secretary-general of the Jewish community of Beirut, who was abducted at the city’s main synagogue in 1984 and has not been seen since. Perhaps, ventures Chitrik, the new Syrian government can help in this regard.

For that matter, I chime in, were the Syrian government to return the remains of iconic spy Eli Cohen, hanged in Damascus’s Marjeh Square in 1965, all of Israel would marvel that this, today, is truly a different Syria.

“You spoke from the heart, and I heard it with my heart,” Kara Ali says at the end of the session.

“Yes, but what are you going to do?” asks Schiffman.

“I’m listening to you, I’m taking notes, and we’ll see how we can work together,” says Kara Ali.

Leaving Idlbi and the Foreign Ministry, we speed to the National Museum of Damascus for what turns out to be the most extraordinary part of our visit.

One member of the group, Jill Joshowitz, is a Judaica curator and archivist based in Pittsburgh who is just completing a book, “Visual Exemplars,” on “Biblical Figures in the Art and Literature of Jewish Late Antiquity.”

She has spent years researching the wall paintings of the Dura-Europos synagogue, a 2,000-year-old shul in eastern Syria that was rediscovered in 1932. The seven-meter-high, vividly-colored frescoes that lined the walls of the synagogue’s assembly hall near-miraculously survived, in part because the Roman army fortified buildings at the city’s walls, including the synagogue, by filling them with earth and debris. Thus the art was encased and protected from destruction and the effects of the elements, and the building lay buried through the millennia until the archaeologists arrived almost a century ago.

The painting-covered walls were dismantled, as was the decorated tile ceiling, and moved to the National Museum decades ago, and there they are known to have remained. But Joshowitz, as we make the journey over, does not know how they are displayed, what condition they are in, or whether anyone — even a visiting, government-invited delegation of Jews — is ever allowed to see them.

“This will either be one of the most disappointing days of my life or one of the very best,” she says as we arrive.

It turns out to be one of the very best.

The wall paintings are, indeed, held at the museum, reassembled in — or rather as — a carefully maintained, unlit room of their own.

They are also, for reasons of preservation, closed to the public. But requests have been made, and authorizations secured, and thus Rima Khawam, the museum chief curator, shows us into what is manifestly a sacred chamber.

We all marvel at the glory on display — floor to high-ceilinged scenes of biblical events, two thousand years old, gloriously, vibrantly colored, with the decorated ceiling atop.

For Joshowitz, this is a life-changing experience — gazing at the material she pored over from a distance, and never seriously expected to see for herself, in all its glory.

We all start asking her to explain the scenes around us — the Binding of Isaac here, the Exodus from Egypt there, the three depictions of the Temple’s menorah. We ask her about the significance of the multiple hands at the top of numerous scenes — from a period, notes Joshowitz, a millennium before Maimonides had clarified that the Divine power could and should not be depicted in places of worship. The artists “somehow knew that they should not attempt to draw God.”

Khawam gravitates toward her, and soon the two are walking slowly around the room, pointing out elements to each other, discussing their significance, maximizing each other’s understanding.

Somehow, all of our drivers, numerous security people, several Syrian army soldiers have been drawn to the room, and are staring, as we all are, open-mouthed at the mesmeric paintings before, above and all around us. “I can’t imagine when a rabbi last got to see this,” says Chitrik, similarly spellbound.

We lose track of time, but the rest of the day’s itinerary beckons. There are other exhibits Khawam wants to show us. Joshowitz asks if, perhaps, she might be allowed to stay with the paintings for a few more minutes while we move on. The request is granted.

Khawam has one more surprise, which she apparently decides to show us on the spur of the moment. She leads us to a different part of the museum complex, to an office turned improvised storeroom far from the public eye.

This room, she says, holds material from the destroyed synagogue at Jobar — the scene of our first stop yesterday. It was brought here during the Bashar al-Assad presidency, in 2017, “and now we are keeping it until it can be exhibited in a different way or at least restored.”

We crowd into the small room. Near the door is a large container with mainly fairly modern synagogue relics — including a Ner Tamid (Eternal Flame) lamp, an Ottoman-era light, and material that hung from the walls. At the far end of the room, in ammunition-style wooden crates, are Torah scrolls, long since robbed of their traditional coverings, vulnerable parchment relics from the war zone.

“Everything here has the residue of the fire and fighting,” says Khawam. “There are many materials — wood, textile, leather, metal — and every material needs different restoration. We have experts, but we also lack restoration materials for our heritage. It was not easy to manage the restoration of our own archaeology. We are trying to fulfill our responsibility to maintain our collections in a good state — for preservation, protection and restoration.”

What, I ask her, does she need? Does she need Jewish expertise for these artifacts, which are mainly modern rather than archaeological? “From any international experts,” she replies.

She then allows me to take three photographs of the room, pressing me to take care to stress her message above — that they are trying to take responsible care of this material, so that it can be preserved and made available for others to see.

We speed again through the packed, chaotic streets — much more jammed than months ago, I’m told, in part because restrictions on imported cars have been lifted — to meet two government ministers. Both of them exude goodwill to this Jewish group, and steer clear of any Israel-related controversy.

Both also convey the sense of how fateful a moment this is for the new leadership — that there is a country to try to stabilize, heal and rebuild, and success is anything but guaranteed.

This is the only chance for Syria. If we don’t support this opportunity, Syria will be gone. And it will be a disaster with terrible implications for Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon and northern Israel

Mohammad Nidal al-Shaar, the minister of economy and industry, who managed to resign intact from a similar role in the Assad era, says Syria “is at a turning point… Before we had grudges and slogans, now we have to have togetherness and cooperation.”

“This is the only chance for Syria,” he says with searing conviction, when explaining why it took him all of three minutes to accept Sharaa’s invitation to take this job. “If we don’t support this opportunity, Syria will be gone. And it will be a disaster with terrible implications for Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon and northern Israel.”

Shaar says the new leadership is “starting from sub-zero, but that also means an opportunity to start afresh,” with “new spirit and new management.” In his field, that means moving to a “free, competitive, economy with checks and balances… from an economy that was chaotic.”

More generally, he goes on, “I believe there is a self-correcting mechanism: There was something wrong; we have to fix it.”

He says he thinks that “the world has decided that Syria is going to be a stable country — as it did with South Korea.”

“Convey to your American people what you have seen,” he urges the group. “Syria is friendly. It is open to anyone. We will use our resources to benefit ourselves and our neighbors.”

Syria has many resources, he says, although not all of them, in the northeast, are under the leadership’s control. Asked how America can help, he stresses: “We want technology, not commodities.”

How sad, I think to myself, that he would not be naturally looking to Israel for that kind of assistance, when he just might have done so before Hamas’s invasion and massacre, and the start of our two-year-old ongoing war.

When I ask him how he envisages relations between Israel and Syria, he says he knows there are “some negotiations between us” and that “some things need time to massage.”

“Your visit,” he says, to smiles in the room, “is one such massage.”

All the officials we meet appear dedicated and competent. Professor al-Shaar is an exceptionally well-trained and experienced economist, a former chief of Market Management at Fannie Mae and economic adviser at the World Bank. I resist the impulse to start making comparisons in my head with some of Israel’s ministerial representatives. I do wonder, however, how a leadership that was until recently focused on a jihadist ideology, working violently to remove a loathed regime, has so rapidly built a hierarchy capable of identifying officials determined to try to build a better future for their country, who in turn are ready and willing to work with Sharaa, conscious of the urgency of the hour.

As we leave Shaar’s office, and people line up to be pictured with him, I ask him if he’s okay to be pictured alongside the Israeli journalist in the group. Of course, he says.

And as we head to the elevators, a delegation from the Czech Republic is waiting to meet with him — on the conveyor belt of supporters and potential investors. We all take more photographs together.

Steven Dishler, the assistant vice president of International & Public Affairs at the Jewish United Fund of Metropolitan Chicago, points out quietly to me that Syria suffers long-term drought and is currently enduring one of the worst such periods. There is so much Israel could do to help in terms of drip irrigation, water reclamation and other areas of proven Israeli expertise. Maybe it can yet.

Hind Aboud Kabawat, the minister of social affairs and labor, the only Christian and the only woman in the transitional government, says she grew up with Bashar al-Assad — “went to the French school with him” in Damascus — and met him later too.

Of Assad, she says, “You say ‘no’, and it’s your last day.” Of Sharaa, “He listens to us. We don’t have to say yes. You can say no, and explain. He wants dialogue.”

An accomplished opposition figure, legal counsel, academic and activist, Kabawat says the new leadership’s policy appears to be to put good people in the right jobs.

“I’m treated as an equal. I say what I want. Nobody is giving me orders here. We do day-to-day work” — as in, serious work — including tackling unemployment, which she estimates is at some 60 percent.

When somebody asks her why she took the job, she, appropriately for our group, quotes Hillel: “If not me, who? If not now, when?”

We packed in an immense amount, but you don’t get to know a country in 48 hours. Least of all, a country at a fateful moment, perched between disintegration and restoration, with a transitional leadership hitherto notorious for Islamic extremism and unproven in nation-building.

We barely left the heart of the capital city, something of a bubble, relatively untouched by the war. One of the Foreign Ministry officials with us had never been to Jobar, a few minutes’ drive away, and was deeply affected by the devastation we all saw there.

We were hosted by a government intent on showing a welcoming face to the developed world, seeking stability and projecting a strategic desire to maintain it. Ahmed al-Sharaa won over US President Donald Trump within minutes at their meeting in Saudi Arabia in May. “Young, attractive guy. Tough guy. Strong past. Very strong past. Fighter. He’s got a real shot at holding it together,” said Trump, immediately lifting sanctions on Syria and encouraging Sharaa to join the Abraham Accords when the time is ripe.

The Syrian president is taking a large delegation to the UN General Assembly next week. He and his astutely chosen ministers and officials will likely make many more friends on that trip — in huge contrast to the near-universally isolated and denigrated Israel.

The officials we met know this is a make-or-break period for Syria, that they don’t have much time to heal a broken nation. Strategic success will not come quickly; failure would be immediate.

The Syrian president is taking a large delegation to the UN General Assembly next week. He and his astutely chosen ministers and officials will likely make many more friends on that trip — in huge contrast to the near-universally isolated and denigrated Israel

I’d had no idea what I’d encounter in Damascus — whether, despite printed assurances, they’d let me in; whether my making explicit in our meetings that I am the editor of The Times of Israel, a journalist from Jerusalem, would cause dismay or worse.

I also did not know what it would be like to walk around Damascus in the company of rabbis and scholars, clearly Jewish and not particularly fast on our feet. Anything can happen at any time of course, but in our 48 hours, nothing adverse did.

Lopatin in his kippa, Chitrik with his hat, Schiffman with his flowing beard were met with warmth and respect in every encounter I witnessed — from official events to strolling in the main souk alongside the working people of Damascus.

As Chitrik and I walked back toward the hotel through an alley on Tuesday evening, a middle-aged man pulled up alongside us on his small motorbike and motioned to Chitrik. He wanted a selfie.

Chitrik obliged, and he smiled and was on his way. You could not have choreographed a more emblematic moment.