In the summer of 1988, I discovered professional wrestling. My family had recently moved from Utah to Connecticut. And having not yet made any new friends to run around with, one Saturday morning, I got up, took my bowl of cereal into the family room, and flipped around the channels until I stumbled upon a show that was unlike anything I had ever seen before, a show called WWF Superstars of Wrestling.

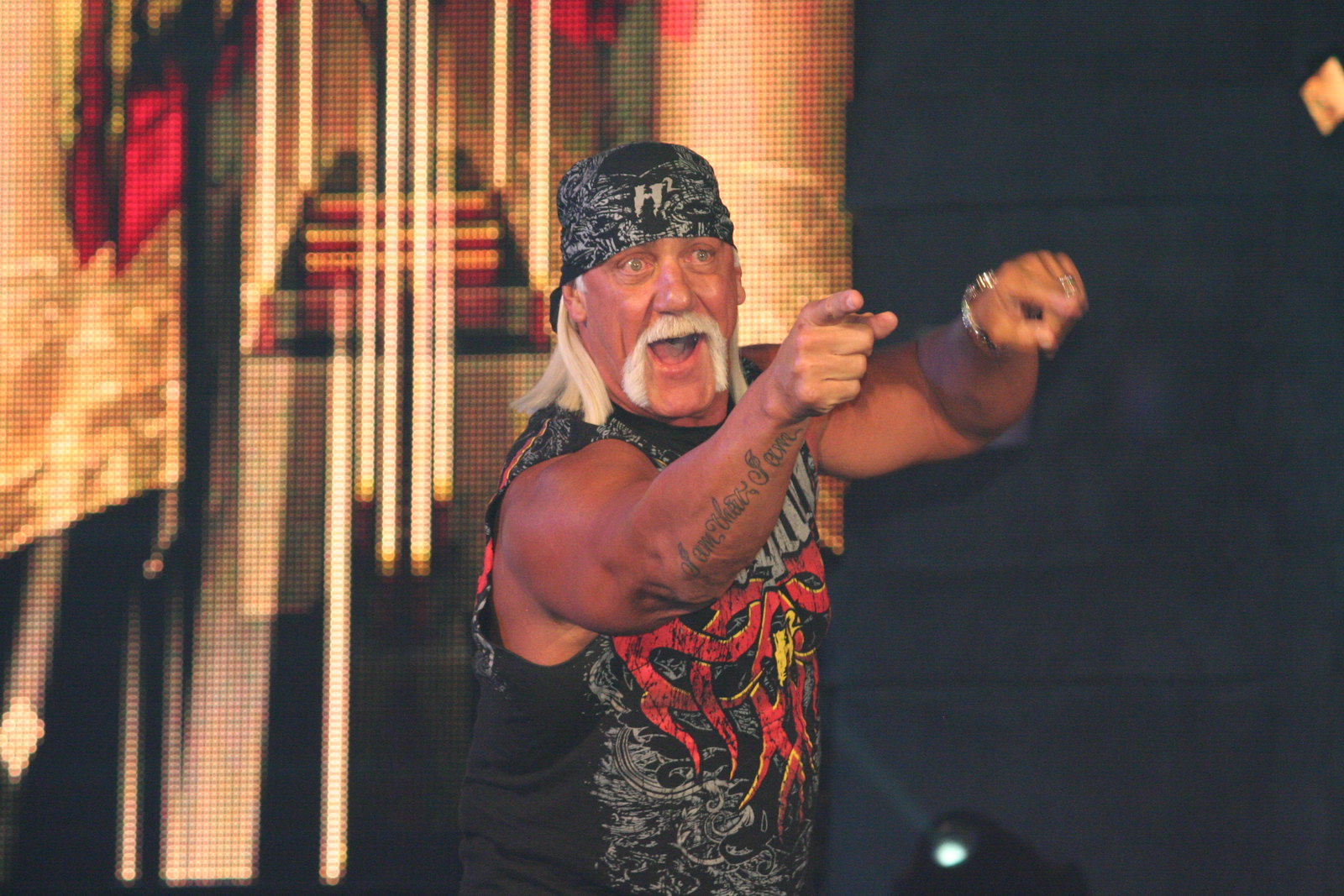

I was instantly addicted. To a 7-year-old boy, a bunch of musclebound maniacs beating each other to a pulp in a modified boxing ring would have been enthralling enough. But this wasn’t just violence. It was violence with storylines and pyrotechnics, costumes and theme music. This was a world where the virtuous heroes brought justice to the sneering, cheating villains by physically dominating them with bodyslams and suplexes. And it was instantly clear to me that the hero atop the pro-wrestling mountain was this shirt-ripping, flag-waving, balding Hercules named Hulk Hogan.

Born in Augusta, Georgia, in 1953, Terry Gene Bollea was an aspiring musician before deciding to apply his 6’7” frame to professional wrestling. After spending time in smaller promotions, Bollea worked his way up to the WWF (now WWE), where, in 1979, he received the name “Hulk Hogan” because promoter Vince McMahon Sr. wanted someone to appeal to Irish-American fans.

In a few years, however, Hogan’s appeal would go far beyond what McMahon Sr. had imagined. When Vince McMahon Jr. bought his father’s promotion, he established Hogan as the face of the company in his attempt to bring professional wrestling into the mainstream. It worked marvelously. While the sports-adjacent enterprise had always had its own stars who were extremely popular with fans, men like Bruno Sammartino, Hogan was the first crossover star, the first true household name. He graced the cover of Sports Illustrated. He hosted Saturday Night Live. Like Elvis, he starred in myriad terrible movies. Even my mother, a woman who couldn’t have told you the names of five NBA stars in the late ’80s, knew who Hulk Hogan was.

In later years, Hulk Hogan’s fictional aura would suffer at the hands of Terry Bollea’s real-life failings and sins, including the WWE’s steroid scandal, his sex tape scandal, and, most reputationally destructive of all, the accompanying racial slur scandal. In the days since his death, numerous journalists have written supposedly balanced pieces lamenting Hogan’s supposedly “complicated legacy.” I decline to take this approach for two reasons.

The first is that, for the last few years of his life, Bollea was an active member of a Christian church. He acknowledged he was a sinner and professed his faith in Jesus Christ as his Savior. Through that faith, Terry Bollea received the blood of Christ that washed away all his scandalous behavior, erasing it from existence. And when such a man dies, I think it’s fitting to speak of his sins the way God does — as lifeless things that no longer condemn the man.

The other reason I hesitate to dwell on Bollea’s sins is that they are largely irrelevant to the myth of the muscle man I loved growing up. Hulk Hogan was always far more of an idea than a person. He was Creatine Roy Rogers, a shirt-ripping symbol that transcended the man portraying him.

A few weeks into my newfound obsession with professional wrestling, my mom walked into the family room as I was watching Superstars.

“You know this is fake, right?” she asked, perhaps because she wanted to discourage me from watching or perhaps because she didn’t want me to be disappointed when I figured it out myself later on. Either way, I vividly remember pausing for a brief moment after she broke the news to me before thinking to myself, “I don’t care. I still love it.”

I couldn’t have told you why it didn’t make any difference to me at the time, but I can quite easily now. I loved professional wrestling, and still do, because it was primal theater. It was simple stories of good versus evil told with fists and dropkicks. And Hulk Hogan was the embodiment of the good. He was virtue with muscles.

It didn’t matter that Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri, the man playing the Iron Sheik, didn’t really hate America. What mattered was that the American spirit can’t be conquered, something Hulk Hogan proved when he burst forth from the camel clutch and won the title from the Sheik in Madison Square Garden.

It didn’t matter that Andre the Giant had already been bodyslammed several times before Hogan supposedly first did it at Wrestlemania III. What mattered was that Hogan proved giants could be conquered, and that we could conquer our own gargantuan foes, when he put that colossal Frenchman on the ground.

It didn’t matter that King Kong Bundy or Randy Savage weren’t really hurting Hogan when he “hulked up” by jumping up from the mat, stomping around the ring, shaking his arms, and then smashing his opponents to pieces. What mattered was that we could hulk up too, that we could refuse to be conquered, that we could also snatch victory from the jaws of defeat if we said our prayers and took our vitamins.

As silly as pro wrestling can be, I’m glad I discovered it as a child. I’m glad Hulk Hogan taught a short, friendless, far-sighted, 7-year-old dork not to see himself as a victim but as a champion in training. I’m thankful to Terry Bollea for playing the role of Hulk Hogan. And I’m thankful Bollea came to know the realest victory of all, Jesus Christ’s victory over sin, death, and the devil.

Rest in peace, brother.