For the whole of human history, man has simultaneously shirked from work, sought respite from it, delighted in it, and found it a necessity. Even while seeking to avoid it, he also would not perfectly enjoy a permanent escape from it, for we yearn to achieve something worthwhile and to see that what we have done is good.

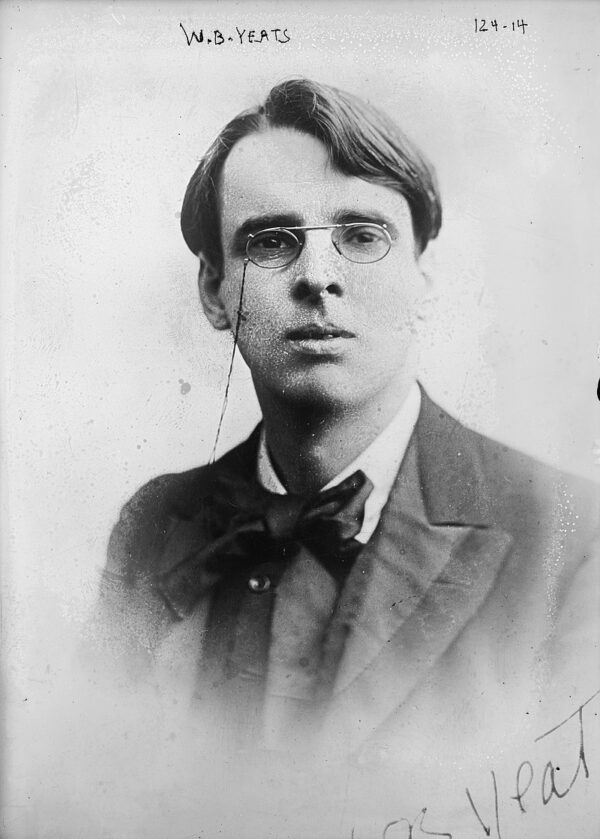

William Butler Yeats published his poem “Adam’s Curse” in 1903, and from the title it is immediately apparent that two things are foremost in his thoughts in the poem: work and mortality.

In the book of Genesis, God gives three punishments: one to the serpent, one to Eve, and one to Adam. The final command consigns Adam to a life of work in which he must till and cultivate the land in order to bring forth his food. The other part of the command states that the ground which is to be his portion in life will also be his resting place in death.

“Adam’s Curse,” composed of heroic couplets (pairs of rhyming iambic lines), presents us with a scene at the close of summer as the speaker sits with the woman he loves and her sister. As this is an autobiographical poem, the two women are understood to be Maud Gonne and her sister Kathleen.

As Yeats relays their conversation, the group touches upon the important truth that we cannot create a thing of beauty without work, and even in the poem’s melancholy conclusion Yeats demonstrates why it is better to work towards beauty than to not pursue it at all.

The initial topic of the group’s conversation is poetry. Yeats paints an idyllic picture for us in the opening lines as he sets the scene:

We sat together at one summer’s end,

That beautiful mild woman, your close friend,

And you and I, and talked of poetry.

It becomes immediately evident that while the conversation in the poem is shared primarily with the sister of his beloved, the poem itself is addressed to the one the speaker loves. The remainder of the first stanza is the articulation of his thoughts on poetry:

I said, ‘A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

Better go down upon your marrow-bones

And scrub a kitchen pavement, or break stones

Like an old pauper, in all kinds of weather;

For to articulate sweet sounds together

Is to work harder than all these, and yet

Be thought an idler by the noisy set

Of bankers, schoolmasters, and clergymen

The martyrs call the world.’

The religious undertone of the final line creates a distinction between society and those deemed indolent by the “noisy set” because their work takes on a quieter form or is seen as less important. Yeats instead claims that the work of a poet is all the more difficult because it must seem as though no work has been done at all: The work of hours must seem a moment’s thought, or else the poet ought to turn his hand to other work.

With the second stanza comes a second voice, and as Kathleen speaks, the topic shifts to beauty in general:

And thereupon

That beautiful mild woman for whose sake

There’s many a one shall find out all heartache

On finding that her voice is sweet and low

Replied, “To be born woman is to know—

Although they do not talk of it at school—

That we must labour to be beautiful.”

I said, ‘It’s certain there is no fine thing

Since Adam’s fall but needs much labouring.

There have been lovers who thought love should be

So much compounded of high courtesy

That they would sigh and quote with learned looks

Precedents out of beautiful old books;

Yet now it seems an idle trade enough.’

With this stanza, we understand Yeats’s idea of a “fine thing” to be a beauty that seems effortless and natural even when is the product of time and care. A woman’s beauty, according to Kathleen, is the result of some degree of work, and yet this cannot be mentioned because to do so would break the illusion of it as effortless and unconscious. The same is true of poetry in which a single line of verse is the work of hours but must seem nothing more than a moment’s thought.

Yeats mentions two types of work that are perceived as idleness: poetry, which isn’t considered work at all, and love, which is viewed as not requiring work in the present day. The hard work which seems a moment’s thought turns to the thoughtless work of a moment, and we see that in Yeats’s view, what he distinguishes as “the world” is all at once bustling and idle.

For all their noise, as mentioned in the first stanza, those belonging to the world won’t direct their energy towards the creation of fine things. The dialogue in the poem closes on a melancholy note, a presentiment that love itself is becoming a lost art.

As the summer draws to an end, a sense of finality and lack of time lingers over the company. In the third section no one speaks at all, as though the final words of the wordsmith have crafted a silence:

We sat grown quiet at the name of love;

We saw the last embers of daylight die,

And in the trembling blue-green of the sky

A moon, worn as if it had been a shell

Washed by time’s waters as they rose and fell

About the stars and broke in days and years.

I had a thought for no one’s but your ears:

That you were beautiful, and that I strove

To love you in the old high way of love;

That it had all seemed happy, and yet we’d grown

As weary-hearted as that hollow moon.

Work done well confers dignity and brings the reward of rest in the completion of a thing of beauty, in seeing that what you have done is good. Instead, Yeats is left with a sense of weariness rather than restfulness. In the moment when he might rest in recognizing the beauty of his beloved, instead his thoughts are drawn to the awareness that no beauty, no matter how much work is devoted to it, will be able to last forever in this world.

He projects his inner state onto the moon, which seems hollowed out because it now mirrors his sentiments. All of time seems like the ebb and flow of an ocean breaking in waves upon the shore, slowly eroding what has been established and known, loved and valued.

The silence that descends upon the company is the result of the awareness that, to a certain extent, they know the end of their story: to dust they shall return. The two women, as described by Yeats, are both examples of beauty subject to the passing of time.

In the last few lines, the speaker reveals to the reader a thought that he says is for no one to hear except the woman he is addressing. He has sought to love her in the “old high way of love,” and yet both he and his beloved are left empty. The melancholy conclusion of the poem is not because they cannot recognize the goodness of their work but because they feel a sense of futility in the impermanence of it.

The precedent of love which Yeats gives us, coming out of a beautiful old book, is the example of Adam and Eve. Adam, having fallen after being led into sin by Eve, shares in the exile from the Garden of Eden with her, and they shoulder life’s burdens together knowing their lives will always be tinged with sorrow in the awareness that their life together must come to an end. The curse is that, whatever we choose, we cannot successfully avoid activity or mortality; and can only live in denial that we will die.

The alternative to pouring our time and effort into loving well is to join the madding crowd, to be assumed into the cacophony of the world as we attempt to numb ourselves to the awareness of our end. Whatever the conclusion of the company after the conversation in the poem, the reader is left with a sense that, despite the freedom to choose the world, there is no true rest apart from work; as Yeats demonstrates, we cannot help but be drawn to beauty and to desire to work for it.

The negation of this desire does not lead to relaxation but to a frenzied servitude to the vagaries of the world. With this in mind, we forge ahead, combatants against time and the world, conscious that of time there will always be too little but that of our efforts we can never give too much.