It’s a hot summer day. A professor is preparing his lectures in his home office. He stretches and takes a much-needed break. He opens a window of his study to take in some fresh air and sunshine, and of course, to admire his garden. He notes with satisfaction that the seeds he planted the previous spring are growing and blooming. The sun shines on his leafy greens, the tops of carrots, the vines of tomatoes, and—oh no!—lots of weeds.

Too involved in his academic work over the past weeks, he failed to notice how his garden has been overrun with weeds. He goes out and, upon rueful inspection, sees a host of unwelcome plants. They’ve insidiously crept into his rows of squash, beans, and sunflowers. Time to weed.

During the Middle Ages, the garden was symbolically represented in art as the place in ourselves where man’s virtues were cultivated. In 1279, Dominican monk Frere Laurent wrote a moral treatise with an illumination (picture in medieval manuscripts) titled, “The Virtue Garden.”

Later, during the Renaissance, artists portrayed gardens as allegorical settings and drew from classical literature, myths, and legends in their paintings. One story was told of Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and justice, who watched over the celestial Garden of Virtue. It was said that, as the ages passed, her righteous rage grew as she watched the garden be overrun by the weeds of many vices.

Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna (circa 1431–1506) told this story in his painting, “Minerva Chases the Vices from the Garden of Virtue” (1502). Mantegna’s painting symbolically presents the vices that people should remove from themselves.

In the painting Minerva is barefoot and donned in her signature floor-length chiton (Roman gown), wearing her Corinthian battle helmet pushed back to reveal her features. She carries a spear and an aegis, her shield with a Medusa head that wards off evil.

The warrior goddess plunges forward, driving out the vices, who flee in terror. Cupidi, minor dieties with moth-like wings who wreaked havoc with their malicious mischief in the garden, now scatter. Everything is in chaos, as the depraved creatures run here and there struggling to avoid Minerva’s wrath.

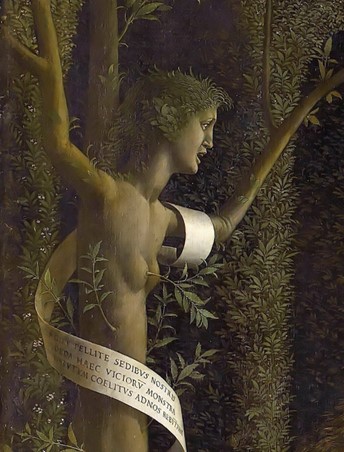

Mantegna used epigraphy, an inscription technique used in the Middle Ages to identify figures or objects, where scrolls, banners or headbands are placed near or on a figure. On the far left is an olive tree with feminine features wrapped in a scroll. According to some sources the banner identifies the figure as Daphne, who was turned into a tree to escape capture by Apollo. Other sources identify the figure as Virtue, who has been bound and unable to grow in the garden.

A figure, holding several babies and identified by a scroll held by a cupidi, looks back terrified as Minerva rushes toward her. In the center, Diana, goddess of chaste love, is saved as she stands on the back of a centaur, symbolizing concupiscence, who pulls at her gown.

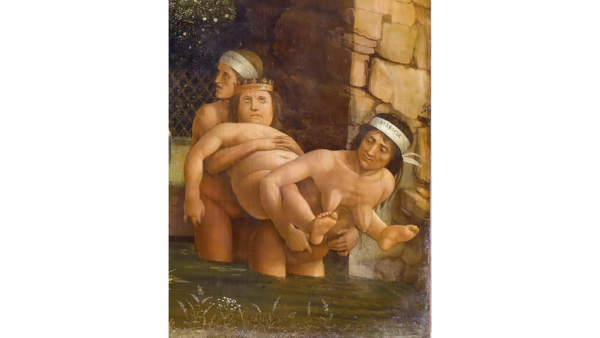

Minerva drives the depraved figures into the swamp. On the bottom right, Avarice and Ingratitude jump into the marsh carrying a dull and lethargic Ignorance who wears a crown. Other vices are driven into the swamp. On the bottom right, Inertia, with a look of fear but who seems to be sight-impaired, pulls Idleness, naked and without arms, with a rope.

In this and later paintings, Mantegna depicted anthropomorphic (inanimate objects with human features) clouds, seen in the upper right. A monkey figure, being pushed into the swamp, also has human attributes. Its arm is up, almost to ward off any blows from the righteous goddess. Nothing escapes the wrath of the goddess.

On the upper right, the figures of Justice, Temperance, and Fortitude await for the vices to be cleaned so they can return to the garden. A white banner coming out of the wall identifies the walled-in virtue of Prudence crying to be released.

During the Italian Renaissance, people of culture and learning added a private office, or studiolo, to their residences as a place to think and reflect, to study the classics, and to enjoy the company of like-minded friends. They designed this private room with the greatest care, using beautiful wood with marquetry, polished floors, and works of art that encouraged reflection and discussion.

In 1491, the marquesa of Mantua, Isabella d’Este, commissioned Mantegna to provide two paintings for her studiolo at one of her two residences, the Castello di San Giorgio in Mantua, Italy. According to the website My Daily Art Display, Mantegna, in his 70s, took four years to complete the Minerva painting.

Isabella was a leading patron of the arts at this time and used the greatest care in her choices. Her biographer wrote:

“In this sanctuary from which the cares and the noise of the outer world were banished, it was Isabella’s dream that the walls should be adorned with paintings giving expression to her ideals of culture and disposing the mind to pure and noble thoughts. …”

Isabella spent more than 30 years adorning her studiolo, where she placed her collection of books, jewelry, antique cameos, and sculptures. She constantly adapted this study to the changing tastes of the court. There were eventually five paintings by artists, including Mantegna’s, in the studiolo, all with the theme of the victory of virtue over vice.

Expert advice from The Spruce tells gardeners to plant densely and use mulch and groundcovers to leave no space for weeds, use other natural methods to get rid of them and, most importantly, never give up rooting out these unwelcome guests in your garden.

Just as Minerva cleaned out her garden so the virtues could return and thrive, so too can we weed out the bad elements in ourselves so our finest qualities can shine. Culling our vices can be hard work, but this allows the fruits of our labor to flourish in the autumn of our life.