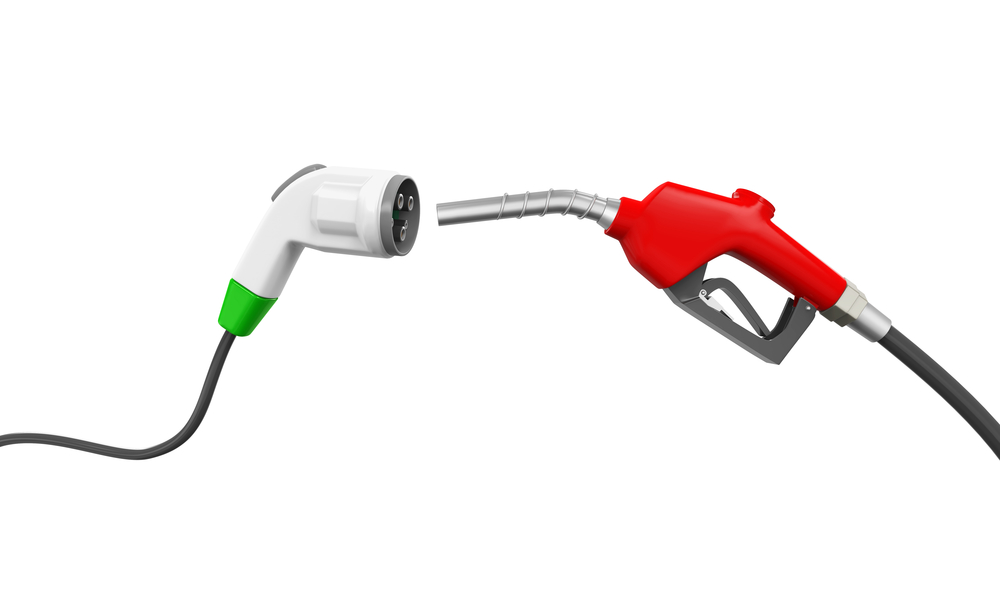

While many car manufacturers, consumers, celebrities, politicians, and states have enthusiastically embraced the idea of replacing internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles with electric vehicles (EVs), there are some aspects of EVs that need to be considered.

EVs are not a new concept. In 1898, Ferdinand Porsche introduced the Egger-Lohner C.2 Phaeton, a fully electric car also known as the P1. Two years later, Porsche introduced the Semper Vivus, a hybrid car that featured an electric motor powered first by a battery, then by combustion engines that fed electrical-power generators.

Henry Ford and Nikola Tesla also experimented with EVs. However, because it was significantly more affordable than the EVs of the time, Ford’s Model T doomed the EV concept and led to the widespread acceptance of ICE vehicles. The gasoline-powered vehicles became widely available thanks to very efficient manufacturing processes. And the fact that gasoline was more readily available than electricity in the United States and many other parts of the world not only played a role in the initial dominance of gasoline-powered vehicles, but also has continued to impact the EV market.

Electricity is a secondary energy source; it must first be generated before it can be used to power anything. In the United States, most electricity is produced by natural gas-fueled power plants, followed by nuclear and coal-fired plants, and then hydroelectric-, wind-, and solar-powered facilities. This means that the argument of EV fans that their cars are superior to fossil-fuel-powered vehicles falls flat; natural gas, a fossil fuel, is projected to be the leading fuel used in electrical generation for the foreseeable future.

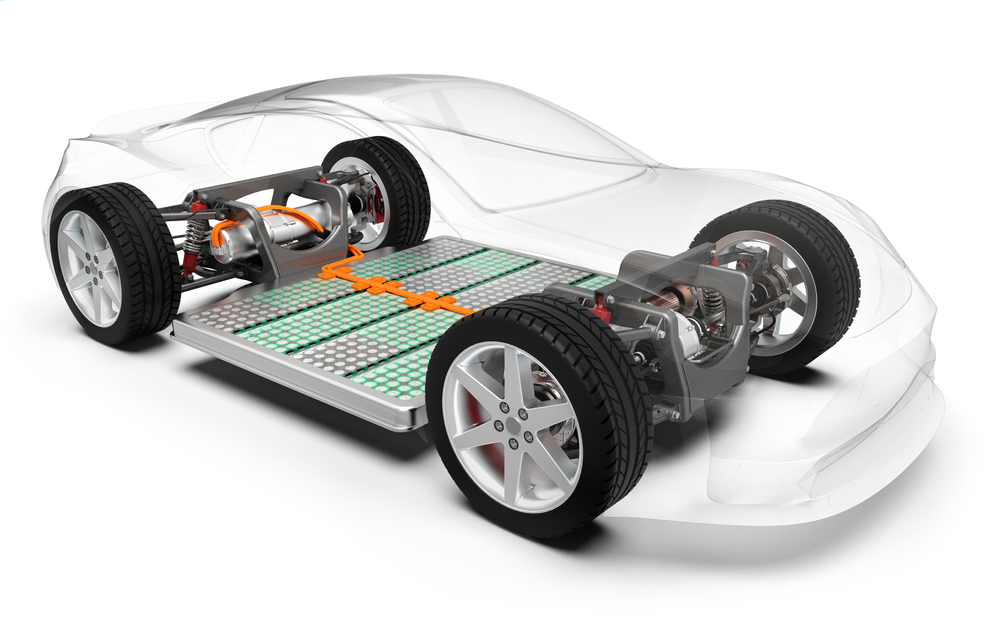

Several other often-overlooked factors should be examined when considering an EV. Among these is the environmental cost of strip-mining for the lithium and cobalt required to manufacture EV batteries. This process creates more harmful emissions than those typically produced in the manufacturing of an ICE vehicle; requires substantial amounts of fresh water; and disrupts the environment, wildlife, and local residents. Also, unlike traditional “wet cell” automotive batteries, which are easily recycled, only about 5 percent of EV batteries are recycled. These batteries are said to have a lifespan of about 10 years, at which time they need to be replaced, sometimes at a cost approaching that of a new EV.

Another battery issue is their flammability; in Florida, several EVs reportedly burst into flames after being exposed to high levels of saltwater caused by storm-related flooding. In one case, the fire completely destroyed a home after spreading from the garage in which the vehicle was parked. Other EVs have been reported to burst into flames after being involved in crashes. These fires required huge amounts of water to extinguish, only to reignite either at the crash scene or after being transported to a storage facility, again requiring a huge amount of water to douse. Because the batteries used in EVs cannot be easily repaired if damaged, an alarming number of EVs are considered total losses by insurance companies after incurring relatively minor damage. Consequently, owners of EVs can be charged much more for insurance coverage in comparison to the cost of covering an ICE-powered vehicle.

Another consideration: The electrical grids in the United States and in other countries need to be overhauled to switch to renewable sources such as solar and wind in order to be able to supply the electricity needed to power the projected large numbers of EVs in the future.

For these and other reasons, Toyota, currently the world’s leading manufacturer of vehicles, isn’t rushing headlong into switching from ICE to EV production. While the firm does offer an EV, a wide range of hybrid vehicles, and the innovative, hydrogen-fueled Mirai, the company is focusing its considerable technological expertise on improving the efficiency of ICE engines. Toyota spokespersons have cited both the lack of recharging facilities in much of the world and the expected continued demand for ICE power as compelling reasons for the company’s stance. And while hydrogen power shows great potential, the only U.S. public refueling stations are located in California.

Even in areas where public EV charging systems are plentiful, there can be issues with finding an open charger that’s capable of fast-charging the vehicle when it’s needed. At present, most private EVs are charged overnight at home; in many cases, a residential electrical system needs to be upgraded to allow fast-charging, otherwise it can take up to 24 hours to fully charge an EV. Extreme heat and cold can reduce the range of an EV by increasing how much energy the vehicle requires under these scenarios, and thus affecting how often the EV needs to be recharged. The standard for an EV driving range seems to be about 250 miles, which falls in line with the typical daily commute of about 50 miles, but could impact longer drives. EV tow vehicles reportedly have seen large drops in actual range when an EV is towing a boat or trailer.

EVs have plusses to be sure, but all sides need to be examined before “plugging in.”