A new study in mice from the University of Missouri-Columbia is shedding light on how diet seems to change the specific bacterial makeup of the gut and instigate a metabolic process that leads to fat buildup in the liver.

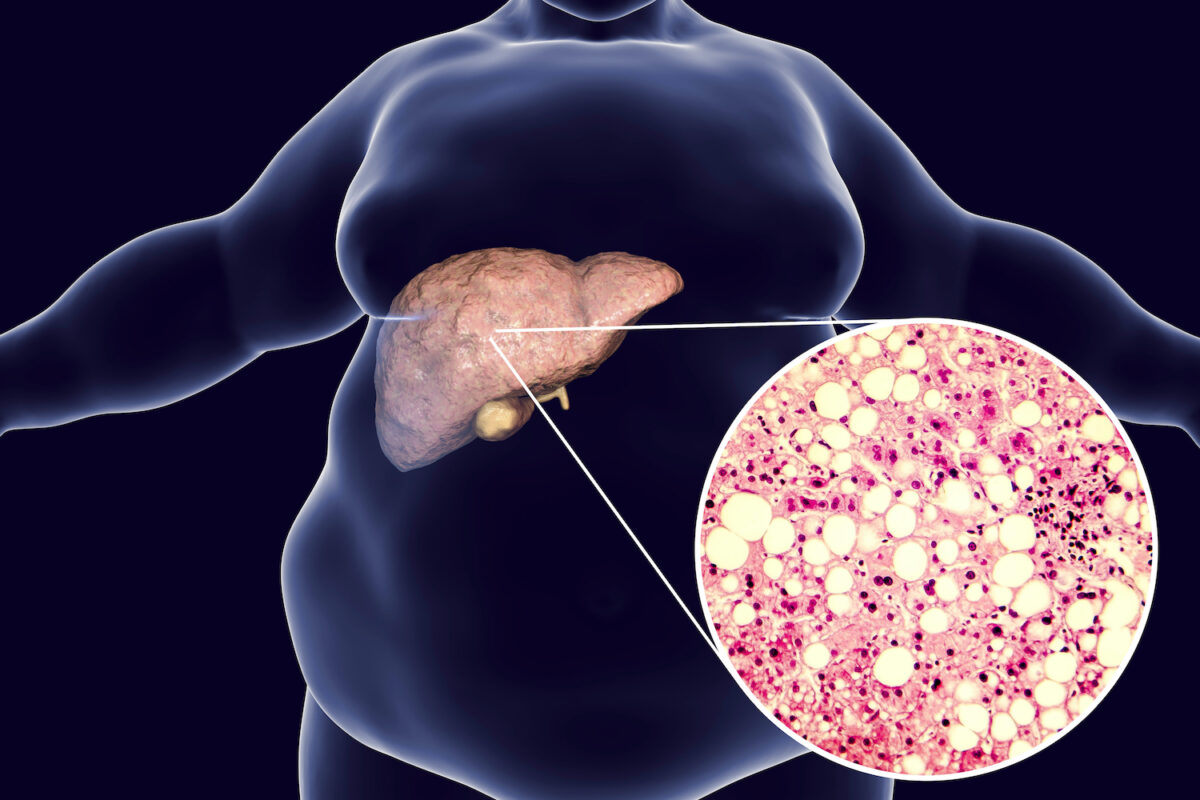

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, also known as fatty liver disease, has few symptoms. However, the risk factors include obesity, insulin resistance or Type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol or triglyceride levels, older age, and traits of metabolic syndrome. Fatty liver disease affects about 24 percent of American adults—many who don’t know they have the disorder—as well as a growing number of children.

Fatty liver disease has been linked to genetics and digestive disorders, but the obvious risk factor—the standard American diet—has been largely confounding. Is a high-fat diet good or bad? Which fats are bad? Is all sugar bad? Is fructose found in fruits and honey okay?

In this study, mice were fed a diet to mimic the Western diet, which is high in both sugar and fat. Researchers were able to identify a specific microbe, called Blautia producta (B. producta), as being responsible for creating the metabolite 2-oleoylglycerol, which is implicated in liver inflammation and fibrosis. The results were published in Nature in January. A buildup of 2-oleoylglycerol has also been found in the livers of people with fatty liver disease.

“We’re just beginning to understand how food and gut microbiota interact to produce metabolites that contribute to the development of liver disease,” said the study’s co-principal investigator, Guangfu Li, in an article published on Science Daily. Li, an associate professor in the departments of surgery and of molecular microbiology and immunology, with a doctorate from Nanjing Medical University in Nanjing, China added, “However, the specific bacteria and metabolites, as well as the underlying mechanisms were not well understood until now. This research is unlocking the how and why.”

Gut microbiota are all the microorganisms—particularly the thousands of species of bacteria—that exist inside the digestive tract and help with the functionality of the human body. It’s often referred to collectively as the gut microbiome, a largely unexplored area of human health. Metabolites are the outcome of many of those functions and include amino acids, lipids, and sugars that are linked to processes like digestion and circulation.

A vital part of the digestive process, the liver receives blood—along with microscopic nutrients and toxins from the diet—through the portal vein. Toxins are removed from the blood and ultimately excreted through urine or feces. Blood is returned into the system, eventually making its way to the heart. The portal vein, along with the small intestine and liver, is called the gut-liver axis.

The liver is the largest solid internal organ, weighing up to five pounds, and performing many complex and vital processes that impact the whole body. The authors of the study conclude that their cellular and molecular mechanistic findings significantly advance understanding of the roles diet, microbiome, and liver function play in fatty liver disease. They did not reply to requests for an interview.

A liver that is storing excess fat can become inflamed and damaged, causing nonalcoholic steatohepatitis—a more progressive form of fatty liver disease. One estimate concludes that 9 million to 15 million Americans suffer from this more advanced state, which causes scarring and cirrhosis and increases the risk of liver cancer, according to the American Liver Foundation. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or fatty hepatitis, is projected to increase by 63 percent between 2015 and 2030.

Considered an emerging health threat, fatty liver disease also impacts American youth. The disorder is the most common form of childhood liver diseases, more than doubling in the last two decades as childhood obesity has risen, says the American Liver Foundation. Between 5 percent and 10 percent of children are estimated to have fatty liver disease.

“Fatty liver disease is a global health epidemic,” Dr. Kevin Staveley-O’Carroll, one of the study’s lead researchers who specializes in liver cancer and surgery, said in a news release. “Not only is it becoming the leading cause of liver cancer and cirrhosis, but many patients I see with other cancers have fatty liver disease and don’t even know it. Often, this makes it impossible for them to undergo potentially curative surgery for their other cancers.”

Though fatty liver disease itself may be silent, the gut microbiome spills its secrets. Besides B.producta seeming to cause liver inflammation and fibrosis in mice, certain other bacterial strains are connected to the liver and to obesity.

Obesity is linked to two dominant phyla, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which can act as biomarkers for related health conditions in stool tests. Other microbiome-based biomarkers, such as Lactobacillales and Verrucomicrobiales can detect early-stage liver fibrosis.

The researchers said their new findings could eventually lead to specific dietary and microbial treatment solutions. As part of the study, mice were treated with an antibiotic cocktail, which was found to reduce liver inflammation and lipid accumulation while reducing fatty liver disease.

There could be complications with this approach in humans, however, as physician guidelines already call for less antibiotic use. The overuse of antibiotics is a medical alarm and has been linked to dysbiosis, where more pathogenic bacteria overtake the gut biome and cause disease. Who’s to say whether antibiotics aren’t a root cause of the dysbiosis involved in fatty liver disease dysbiosis?

Antibiotic overuse is a warning issued in the book “Missing Microbes,” written by Dr. Martin Blaser, chair of the Human Microbiome at Rutgers University, where he also serves as a professor of medicine and pathology and laboratory medicine.

“Of course, our powerful antibiotics could affect our friendly bacteria,” he wrote in the epilogue of the 2014 book. “Everything that changes them has a potential cost to us. We have changed them plenty. The costs are already here, but we are only just beginning to recognize them. They will escalate.”

As much as it seems too soon to make the leap into antibiotic treatment for humans with fatty liver disease, it’s also important to point out the limitations in studies of mice and the microbiome in general.

For an outside perspective on the study, The Epoch Times reached out to Dr. Michael Greger, who started Nutrition Facts, to fill the gap between research on diet and the lack of nutrition training in the medical field. He simply remarked that “there are inherent difficulties extrapolating from rodents to people.”

Nonetheless, it’s the predominant path that research takes, as mice and humans both have gut microbiomes made up of about 90 percent Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. A 2021 article in Microorganisms examined the complications and benefits of this research approach, pointing out that fine-tuned techniques and processes in the lab are translating to more reliable comparisons.

The article concludes: “Despite their limitations, mouse models are still a valuable, practical, and irreplaceable tool for studying human disease. No animal models are 100 percent ideal for modeling human disease.”

If the standard American diet was on trial, this new study would be incriminating new evidence. Knowing the mechanism of action behind the disease confirms that diets high in saturated fats and sugar should be avoided.

Fatty liver disease warrants attention for its problematic nature but also because it can be avoided and reversed. Cleveland Clinic’s website on fatty liver disease warns that untreated cirrhosis of the liver eventually leads to liver failure or liver cancer. The good news is that fatty liver disease is an early warning sign of a completely reversible condition, as the liver is able to regenerate itself to a point.

In addition to keeping to a healthy weight, the clinic recommends the Mediterranean diet, which is high in vegetables, fruits, and healthy fats with moderate fish and poultry consumption.

Diet changes can have rapid effects on fatty liver disease, as Greger pointed out on a 2021 podcast on fatty liver disease and how not to get it.

“One can of soda a day may raise the odds of fatty liver 45 percent, and those eating the equivalent of 14 chicken nuggets’ worth of meat a day have nearly triple the rates of fatty liver, compared to seven nuggets or less,” he said.

Greger suggested the benefits of a plant-based diet as most compatible with lowering the risks of fatty liver disease, but he also pointed out that statistically, there’s another reason sufferers should address their diet.

“Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death among patients with fatty liver disease (not liver failure),” he said. “And we do have randomized controlled trials proving a healthy plant-based diet and lifestyle programs can reverse heart disease—opening up arteries without drugs, without surgery, without stents. Yes, patients with fatty liver disease and fatty hepatitis may indeed eventually develop cirrhosis of the liver, but only if they don’t die of cardiovascular diseases first.”