Egg prices have seen a steady increase over the past few years but price spikes have never been this extraordinary until recently. One Twitter user posted that cartons of 18 eggs (not organic or pasture-raised) cost $10 and have anti-theft alarms attached to them. While inflation and supply chain issues play a role in this, the main culprit behind the price spike is a raging avian flu pandemic impacting 58.59 million birds and counting.

Viruses mutate constantly and the flu breaks out every year for all sorts of animals. There are four major types of influenza viruses, types A, B, C, and D, with various strains and variants as well as varying host ranges. These flu strains constantly mutate, which might result in cross-infection with other species or zoonotic transmission to humans, which was the case back in 2009 during the H1N1 swine flu pandemic.

The avian flu, or bird flu, primarily infects wild bird populations. The many strains of the avian flu vary in terms of symptoms and pathogenicity. Often the avian flu can be quite severe for domestic poultry, while not having a significant impact on wild birds.

The avian flu outbreak is commonly believed to start with infections in wild bird populations and then spread to poultry farms. Wild birds usually show little to no symptoms and are quite effective virus carriers. Chickens in large industrial-scale farms usually reside in dense populations where the virus can spread quickly, which has historically been the case.

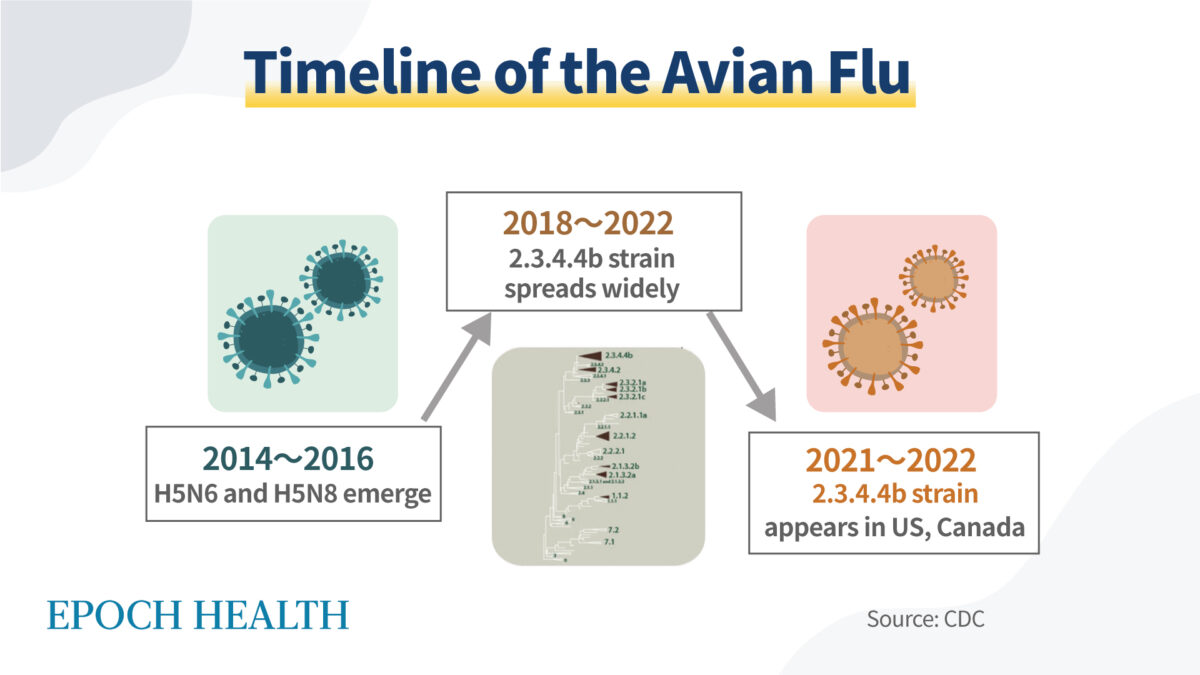

The last time an H5Nx avian flu outbreak happened was back in the 2015–2016 flu season, with H5N6 and H5N8 being the dominant strains. This time, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) risk assessment, the H5N1 virus (pdf) dominated even the wild bird populations and resulted in mass die-offs, both on the farm and in the wild.

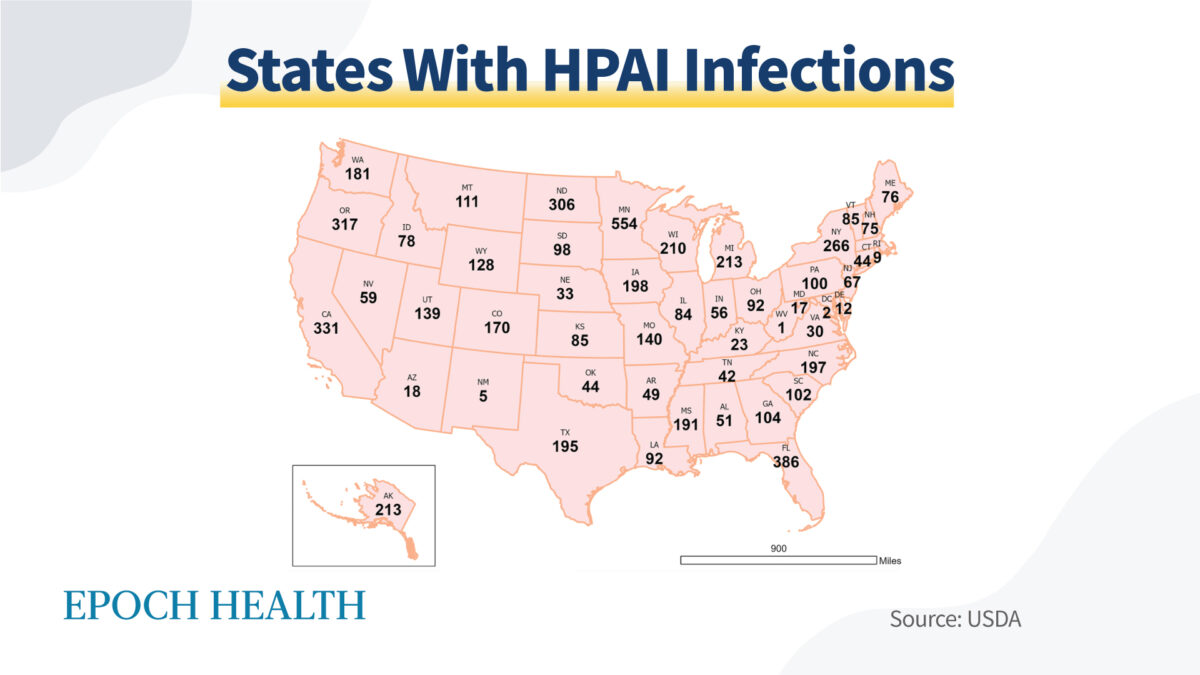

This particular virus clade was carried across the continental United States via migratory birds that traveled across the Central and Mississippi Flyways. Since more infected wild birds have died compared with previous outbreaks, we can blame the high death toll on domestic poultry farms. At the same time, wild and migrating populations severely stricken with the virus can be blamed for its rapid spread, with the possibility of strain mutations.

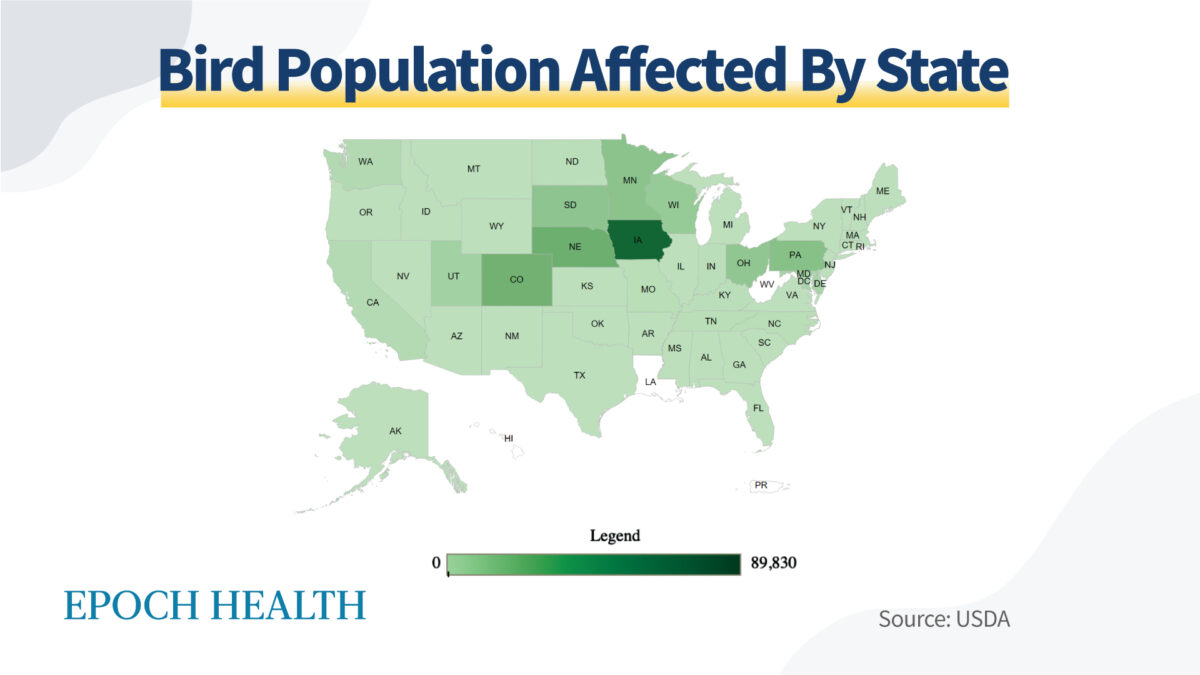

In the United States, Midwestern states have been the most impacted. For example, Colorado and Nebraska each has more than 6 million affected chickens. Iowa has suffered the most under the pandemic, with 15.9 million affected chickens. More than 10 states have a seven-figure infection rate.

Speaking from a global perspective, this pandemic began in 2020 when this highly pathogenic avian influenza strain spread through the migratory birds that travel around Africa, Asia, and Europe. It has been a major cause for concern, as the outbreak in Europe is far worse compared with the United States and has been raging for more than three years. This avian flu outbreak has resulted in massive die-offs both in wild and domestic populations. Australian ABC News reported that the estimated death toll of chickens alone is around half a billion.

It is puzzling why this wave of bird flu outbreaks did not die down during the summer of 2022. Instead, the outbreaks merely simmered down during the warm seasons but continued to affect poultry farms throughout 2022, placing many farms under continuous strain. Many likely left the industry due to the tough conditions. Alongside impacted production due to diseased chickens, it makes sense that the supply of fresh eggs in the market was greatly reduced and prices skyrocketed.

This new H5H1 clade is still spreading to a growing number of species including mammals, and recently a mink farm in Spain. Other countries hit hard by the virus include the Netherlands, where the virus caused the death of hundreds of red knots (Calidris canutus) and other Northern European shorebirds.

The Hula Valley region in Israel has also suffered the loss of more than 8,000 cranes (pdf). Globally threatened species such as the marbled teal (Marmoronetta angustirostris) and hundreds of great white pelicans have also died off in parts of West Africa as well as in Europe.

Case reports as seen in the WHO risk assessment have surfaced on animals ranging from otters and black bears to seals and skunks that have been infected with the H5N1 virus. Not only is this virus more deadly, but the fact that it is also infecting many other species, including mammals, has fueled a concern that it could infect humans and turn into another pandemic.

The fear that this avian flu strain can transmit to humans and become a new pandemic is not ungrounded, yet recent data show that it is not likely to happen with the current 2.3.4.4b clade. First off, humans lack the proper receptors for the virus to effectively infect us. We are not in what is called the “host range” of the virus, or the list of species the virus can infect.

However, according to the WHO assessment, by the end of January 2023, there had been six case reports worldwide of this avian flu infecting humans. These include two in Spain, and one each in the United States, Vietnam, the UK, and China. All four cases in Europe and North America were relatively mild or asymptomatic, while the cases in Asia were much more severe.

The patient with severe symptoms in Vietnam managed to recover while the patient in China did not. All of these cases had been linked to infected poultry through the patients’ participation in activities that responded to poultry outbreaks, exposure to backyard holdings, or live animal markets.

In February 2023, there was another H5N1 human infection case reported in Cambodia wherein a young girl died. Dead wild birds were also identified in the river near her village.

However, based on the virus sequences identified in this clade 2.3.4.4b, the WHO assessment said there are no signs of mammalian adaptation, meaning that these viruses can’t cause a large-scale outbreak in mammals and humans. The virus does not show resistance toward key antivirals such as neuraminidase inhibitors, either.

However, close observation on an international scale is still needed to monitor any further mutations that might influence infectivity, pathogenicity, and host range adaptation.

Many people likely operate private, small-scale poultry farms, and there are actions these people can take to ensure they and their birds stay safe.

First of all, keep in mind that it is nearly impossible for the avian flu to infect you. Even so, avoid coming into close contact with sick wild birds, especially ones that are seriously diseased or dead. It is best to report any findings to local authorities.

Those involved in culling and disposing of infected birds or animals should wear appropriate protective equipment and abide by local regulations.

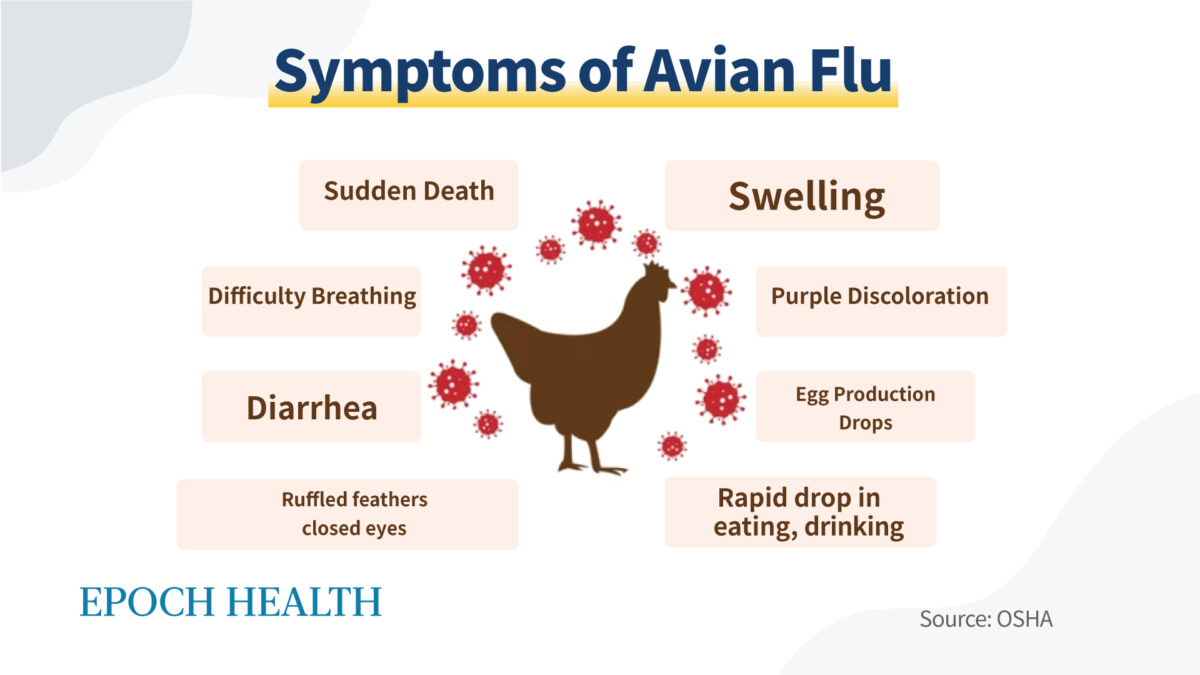

There are a few common symptoms of the 2023 bird flu that farmers and homesteaders should keep an eye on.

It is probably no coincidence that a major bird flu outbreak started almost simultaneously with the human COVID pandemic. It is hard to put a label on the scale of this outbreak, as the number of wild bird deaths is difficult to determine. We don’t exactly know how many people truly died of COVID, either, as reports might be neither timely nor accurate for various medical or political reasons.

However, the increasing number of pandemics might constitute a significant change in the Earth’s ecosystems. Is Mother Earth sending us an important message that we don’t fully appreciate yet? Prophecies have been passed down in various indigenous cultures, such as one in which the Mayans mentioned the Earth’s regeneration period. Should this be the case, do we all need to undergo major changes?

It is time to evaluate our behavior. The standard response to the bird flu outbreak has been to cull the whole chicken population (tens of thousands to millions of birds) in which only one infection was identified. This massive culling is a cruel measure commonly adopted as the most cost-effective way of dealing with such a situation. It is simply cheaper for the owners to raise new batches of poultry rather than treat chickens. However, does this kind of killing result in good karma?

Meanwhile, the abuse of antibiotics is rampant in the poultry industry. We are creating more undesired consequences for ourselves in terms of more drug-resistant pathogens. It is time to evaluate the ethics of industrial-scale poultry practices and how these practices might contribute to disasters on a global scale.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times. Epoch Health welcomes professional discussion and friendly debate. To submit an opinion piece, please follow these guidelines and submit through our form here.