Every cardiology office in America should be recognizing COVID-19 vaccine-induced myocarditis presenting in young persons, 90 percent are male, with chest pain, effort intolerance, arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest after injections of mRNA vaccines. As I see these patients, the common question is, “When is this over?”

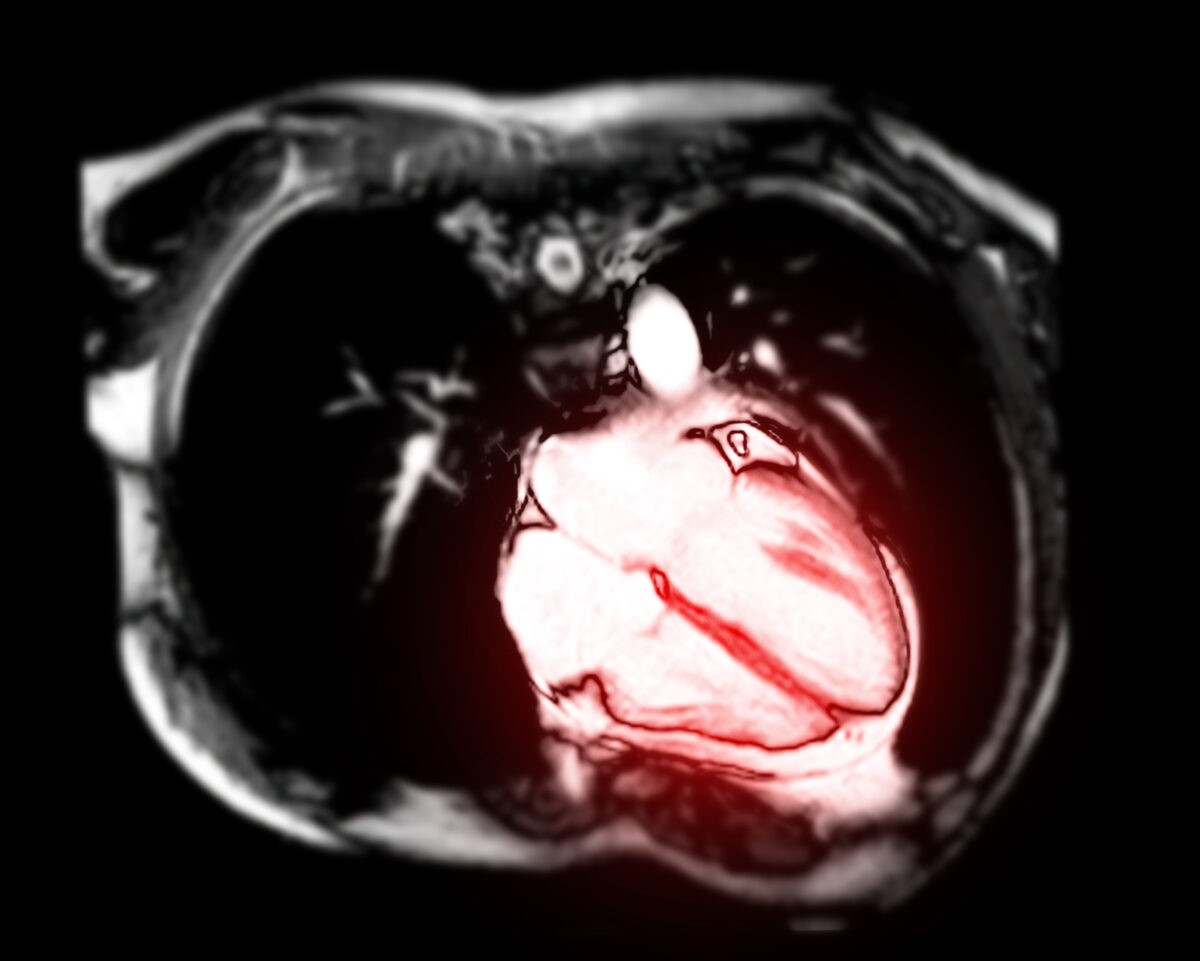

While ECG and blood tests tend to normalize quickly, my concern is that ongoing inflammation is occurring due to continued production of Wuhan Spike protein coded by the long-lasting Pfizer or Moderna mRNA vaccines. While blood tests can give inferences on inflammation, cardiologists also use cardiac MRA to visualize the inflammation, establish the diagnosis, and craft a prognosis. We would hope young teenagers would resolve their MRI results and go on with life. A recent report to the contrary caught my attention.

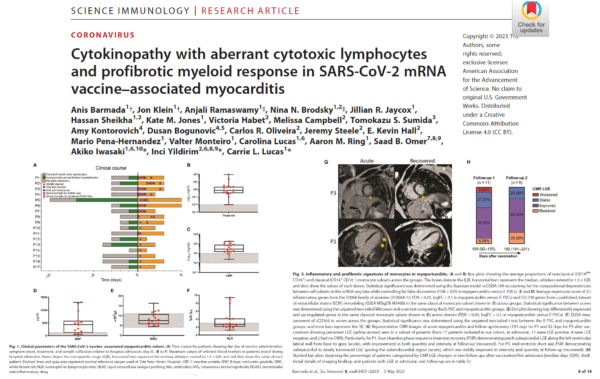

Barmada et al. studied a clinical cohort consisting of 23 patients hospitalized for vaccine-associated myocarditis and/or pericarditis. The cohort was predominately male (87 percent) with an average age of 16.9 plus/minus 2.2 years (ranging from 13 to 21 years). Patients had largely noncontributory past medical histories and were generally healthy before vaccination. Most patients had symptom onset 1 to 4 days after the second dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine.

Six patients either first experienced symptoms after a delay of more than seven days after vaccination or were incidentally positive for SARS-CoV-2 by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing upon hospital admission—these six patients were thus excluded from further analyses, although they potentially reflect the breadth of clinical presentations of vaccine-associated myopericarditis.

The remaining cohort of 17 patients showed no evidence of recent prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, with antibodies to spike (S) protein but not to nucleocapsid (N) protein and negative nasopharyngeal swab reverse transcription quantitative PCR at hospital admission.

While the authors clearly show high levels of inflammatory markers, my attention was drawn to the follow-up MRI scans. As shown in the figure, only 20 percent had resolved their abnormalities (late gadolinium enhancement) at over six months (199 days).

This paper raises questions:

- Is there ongoing heart damage and inflammation at six months?

- Does the LGE in 80 percent represent a permanent “scar” putting these children at risk for future cardiac arrest? These data strongly call for large-scale research into this emerging problem given the large number of potential young persons at risk.

Reposted from Peter A. McCullough’s Substack

◇ Reference:

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times. Epoch Health welcomes professional discussion and friendly debate. To submit an opinion piece, please follow these guidelines and submit through our form here.