When brutal fighting broke out between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the powerful Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group on April 15, human rights monitor and freelance videographer Gouja Ahmed never thought leaving his house had turned from an option into a matter of life and death.

“There are no means to earn money from my job [anymore], but I now have the chance to defend my people’s rights and to protect them through advocacy,” Ahmed tells The Epoch Times via a messaging app, opting to have his location concealed for fear of his own safety.

“Many people are suffering, especially those who depend on daily income,” he says.

“Many don’t have the means to buy food. Most markets have been closed. Soldiers and militias have been looting in these markets. No emergency services are present. The state is missing.”

The fighting pits the country’s de-facto military ruler and head of the armed forces, Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, against his deputy who heads the paramilitary RSF—Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti.

Both rivals claim to be gaining ground but this may just be a reflection of a “media war,” an observer of the unfolding conflict has told The Epoch Times.

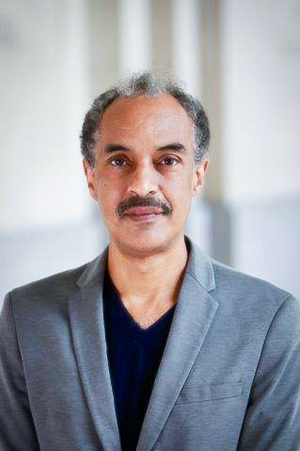

“The situation is fluid so it looks like a stalemate between the two,” said Dr. Khalid Mustafa Medani, associate professor of Political Science and Islamic Studies and Chair of the African Studies Program at the Montreal-based McGill University.

The present conflict was sparked by disagreements over the timeline needed to integrate the RSF into the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) as stipulated in a Dec. 5, 2022, framework agreement.

“Dagalo wanted a 10-year window, [while] Burhan wanted a two-year window,” Khalid told The Epoch Times in an email.

“This is what sparked the conflict and led to Dagalo deploying more troops in the conflict as the two generals [try] to win a military victory.”

He said the framework agreement was “very successful,” and “popular,” and was a good solution to reforming the government, but for the fact that it was “not inclusive enough” and the timeline for signing “too short.”

“This was a mistake, but these mechanics can be rectified after this conflict if domestic and external actors learn from their mistakes.”

Sudanese and foreigners continue to stream out of the capital of Khartoum and other battle zones, as continuous fighting jeopardized a three-day US-brokered ceasefire that was expected to end on April 28.

It was the fourth effort to stop the fighting that resulted from month-long tensions. Several short-lived ceasefires had been agreed upon between the two warring groups over the past week, but they have all failed to hold.

Aid agencies have raised alarms over the crumbling humanitarian situation in a country reliant on outside help.

The Sudanese health ministry has put the number of deaths so far at nearly 500, with more than 4,000 others wounded.

The UN refugee agency says thousands have already fled the violence and that it is bracing for up to 270,000 people to cross from Sudan into neighboring Chad and South Sudan.

Some 15.8 million people in Sudan—a third of the population—already needed humanitarian aid before the latest violence erupted.

The UN refugee agency, UNHCR, says it does not yet have estimates for the numbers headed to other surrounding countries, but there have been reports of chaos at the border with Egypt as Sudanese try to get out of their country.

Other nations are working to get their citizens out.

Ahmed told The Epoch Times that Nyala, a city in southwestern Sudan that hosts the headquarters of the Sudanese Armed Forces is a center of fierce fighting.

“The civilians are paying the prize for this war,” he laments.

“Bullets and even tanks are being used by Sudanese and RSF forces where millions of civilians are living. The situation is really tough for everybody in Sudan, especially those living in Khartoum, northern Sudan, and Darfur state.”

Right now, there is no winner or loser in the conflict, according to Ahmed.

The only “biggest losers” are the Sudanese people.

“Many civilians have been killed and hundreds injured. Just about 200 meters from my home, my neighbor was killed by live bullets in his home on the first day of fighting. Another neighbor was killed days later. Three of my friends have been wounded.”

Ahmed said all what the Sudanese people have been working to achieve for years have been brought to nothing. “Even the process for democratic transition has been destroyed.”

Dagalo of the RSF paramilitary group and Burhan of the Sudanese armed forces worked together in 2019 to overthrow Sudan’s long-serving leader, Omar al-Bashir.

After the coup, a power-sharing government was formed, made up of civilian and military groups.

The plan was for it to run Sudan for a few years and oversee a transition to a completely civilian-run government.

Sudan’s political crisis started in October 2021, when Dagalo and Burhan joined forces and ousted civilian Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok before reinstating him a month later.

After upending the transition to democracy, however, friction between the Sudanese army and the powerful RSF became increasingly visible in recent months, with conflicting public statements, a heavy military presence in Khartoum, and parallel foreign trips by military and RSF leaders.

Despite the growing differences between both men, a lifeline appeared on the cards when civilian and military parties agreed early this month to strike a new political agreement to name a transitional government and pave the way for elections.

However, the signing of the deal was postponed from April 1 to April 6, before being put off for a second time, with a spokesman for the negotiations saying “outstanding issues” needed to be resolved.

James Barnett, Research Fellow at the Washington-based Hudson Institute research think tank, told The Epoch Times that the roots of the conflict in Sudan stretch back to the regime of Omar al-Bashir who, he says “intentionally weakened” his own military in an effort to “kneecap his generals and stave off coups.”

“It may have worked, but only for a time,” Barnett told The Epoch Times in an email.

One way he did so, Barnett said, was by “empowering a series of Darfuri militias” that were organized into the Rapid Support Forces and essentially became a parallel army to the Sudanese Armed Forces.

“The RSF and SAF cooperated to topple Bashir in 2019 but their rivalry grew more acute after this as both sought to prevent the other from becoming the dominant power in the new regime [which was nominally civilian, until a coup in 2021 that put the military in charge].”

The only thing that the RSF and SAF agreed on was “forestalling” civilian rule, according to Barnett.

“Otherwise, the RSF exploited the coup and stalled the transition to increase its power within Sudan’s politics and economy, which made the SAF uneasy.”

As the SAF made efforts to curtail the growing influence of the RSF by subordinating it to military oversight and the paramilitaries responded by gearing up for war.

Khalid of McGill University said that on paper, the RSF is “more willing” to fall under the civilian leadership since it needs a “constituency.”

“But the RSF wants to do so while still being an autonomous military force,” he told The Epoch Times.

“Burhan says he, too, is supportive of being under civilian leadership, but his allies are former members of the National Congress Party (NCP)/Islamist regime and if they influence him, that block is not interested in a civilian regime.

“They want to return to power under a military they can control as in the era of Omar Bashir.”

The two military rivals are less likely to bridge their differences unless there is a stalemate after which the international community forces them to do so, says Khalid.

“This can be done with targeted sanctions on the financial sources of both generals by the international community pressuring them back to the table with civilian leaders,” he said.

“But if either wins outright he will attempt to consolidate his own rule.”

But Barnett believes neither the RSF nor the SAF supports a transition to civilian rule, as both want to “hold power themselves whatever the costs.”

“So whoever wins, it will not be the Sudanese people,” he told The Epoch Times.

“The priority for the United States should be for Sudan to continue and eventually complete its transition to civilian rule. Unfortunately, these clashes mark the death of that already fragile transition for the foreseeable future.”

A recent CNN investigation suggests the Russian mercenary Wagner Group has been supplying the RSF with missiles to aid their fight against Sudan’s army.

Earlier reports had claimed the Kremlin-backed private military company was deploying mercenaries to Sudan and runs a major gold mining concession, while Russia’s government has pressed Sudan to allow Russian warships to dock at its Red Sea port.

“Russia is close to the RSF and certainly sees geopolitical stakes in how this conflict unfolds,” confirms Barnett of the Washington-based Hudson Institute research think tank.

“Russia is very pragmatic in its relations with African countries; after all, it was cozying up to Bashir for several years before Bashir was toppled and then it managed to adapt quickly to the new reality in Sudan and grow closer to the RSF.

“If the SAF triumph over the RSF, they may be hostile to Moscow for a time owing, which would force Russia to again pivot and adjust its approach,” he said, noting however that no outcome of the current fighting will end Russian influence in Sudan.

Khalid dismisses suspicions that Islam and Arabism form the root causes of the present conflict in Sudan.

Rather, he insists, the conflict emanates from the legacy of a regime that used Islamism as an “ideology to rule an authoritarian state.”

“This proved to be a failure as evidenced by the revolution of 2018–2019,” Khalid told The Epoch Times in an email.

“The root of the problem is the top brass of the army fighting to retain their political power and wealth, and a militia leader trying to do the same.”

Evidence of this, Khalid pointed out, is the fact that they cooperated since 2003 in Darfur and in Khartoum, and only started their fight when each felt the other was trying to monopolize the military and political power.

“Sudanese civilian society is now struggling for democracy that respects all traditions and ethnicities.”

As the fighting in Africa’s third largest country rages on with no end in sight, Tibor Nagy, former U.S. assistant secretary of state for African affairs is fearful.

“The fighting will not stop until one of the leaders eliminates the other, chases him into exile, or one side runs out of ammunition,” he told The Epoch Times in an email.