“You can’t paint timid.”

Bold.

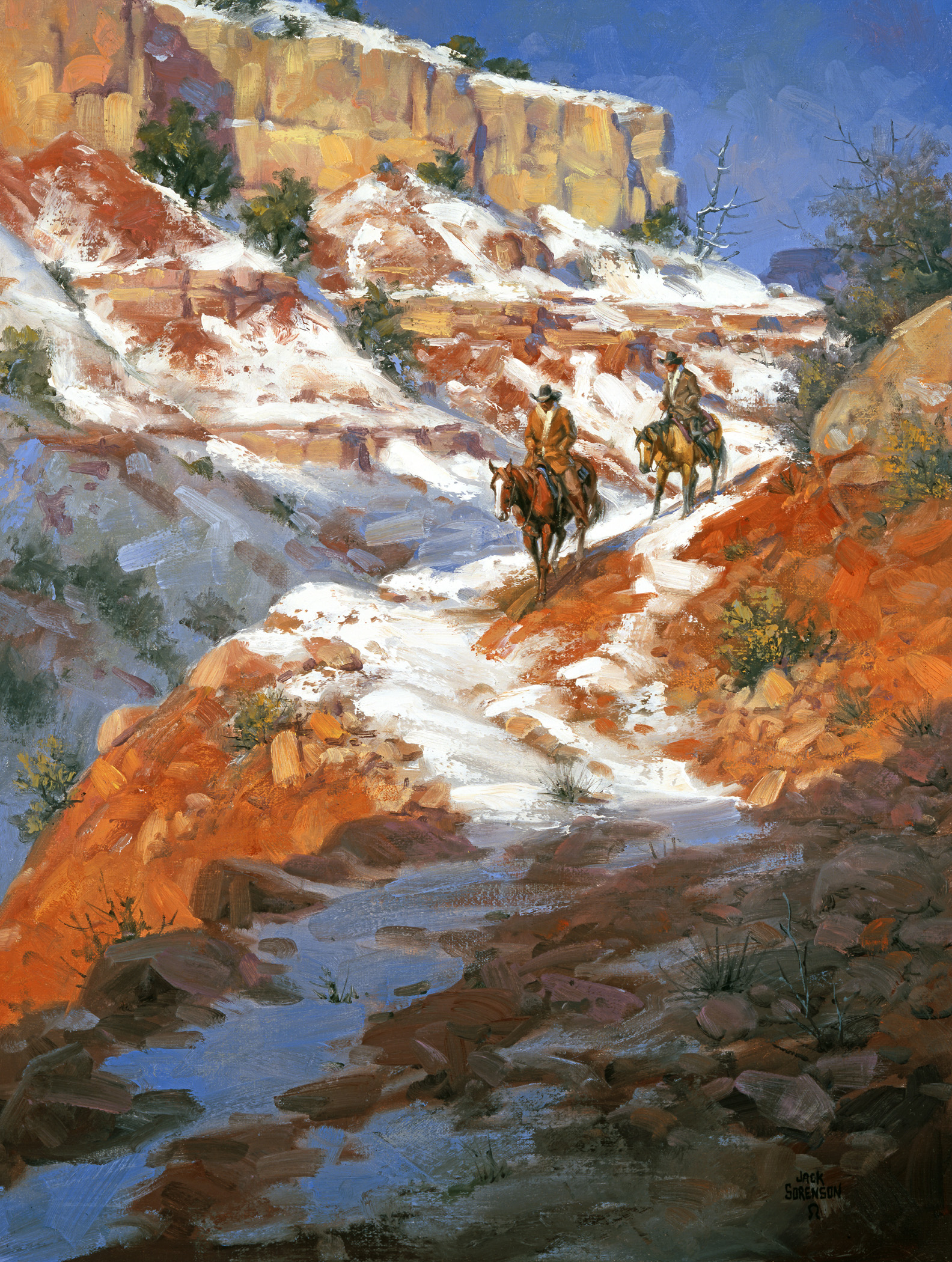

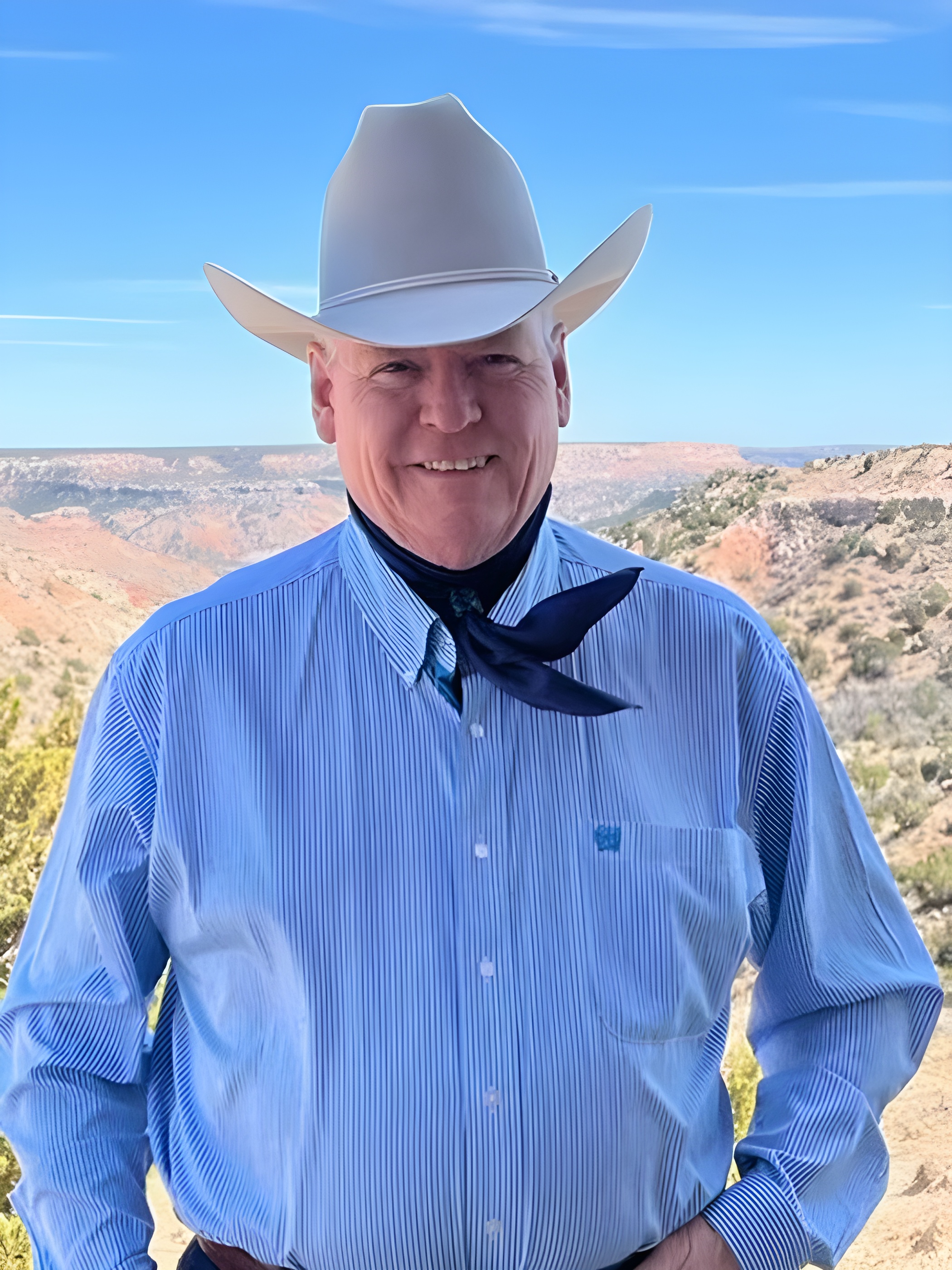

That’s how the cowboy artist from Canyon, Texas, approaches his painting.

“I’d rather paint a bold brush stroke wrong than a timid brush stroke right,” Jack Sorenson, 69, told The Epoch Times.

With 48 years of experience under his belt, rendering the Old West and the New West in oil, Sorenson has soaked up artistic know-how from some of the most talented Western painters in America.

“That’s just the way I approach it,” he said. “And I work fast, much faster than most artists I know. I can do a large painting in a week usually pretty easily.”

Once an idea comes—the story he wants to tell—he starts sketching to work out all of the problems. Then, once he starts painting, he just tries “to paint the heck out of it.”

His Texas ranch upbringing alongside raw talent and numerous great teachers converged to make Sorenson the Western artist he is today.

Like many painters, Sorenson’s journey to professionalism began with raw ability.

“The first day of first grade, my teacher called my mom and said, ‘I think Jack is a prodigy,’” he said. “And my mom didn’t know what that meant; she said, ‘Oh, gosh, what did he do now?’”

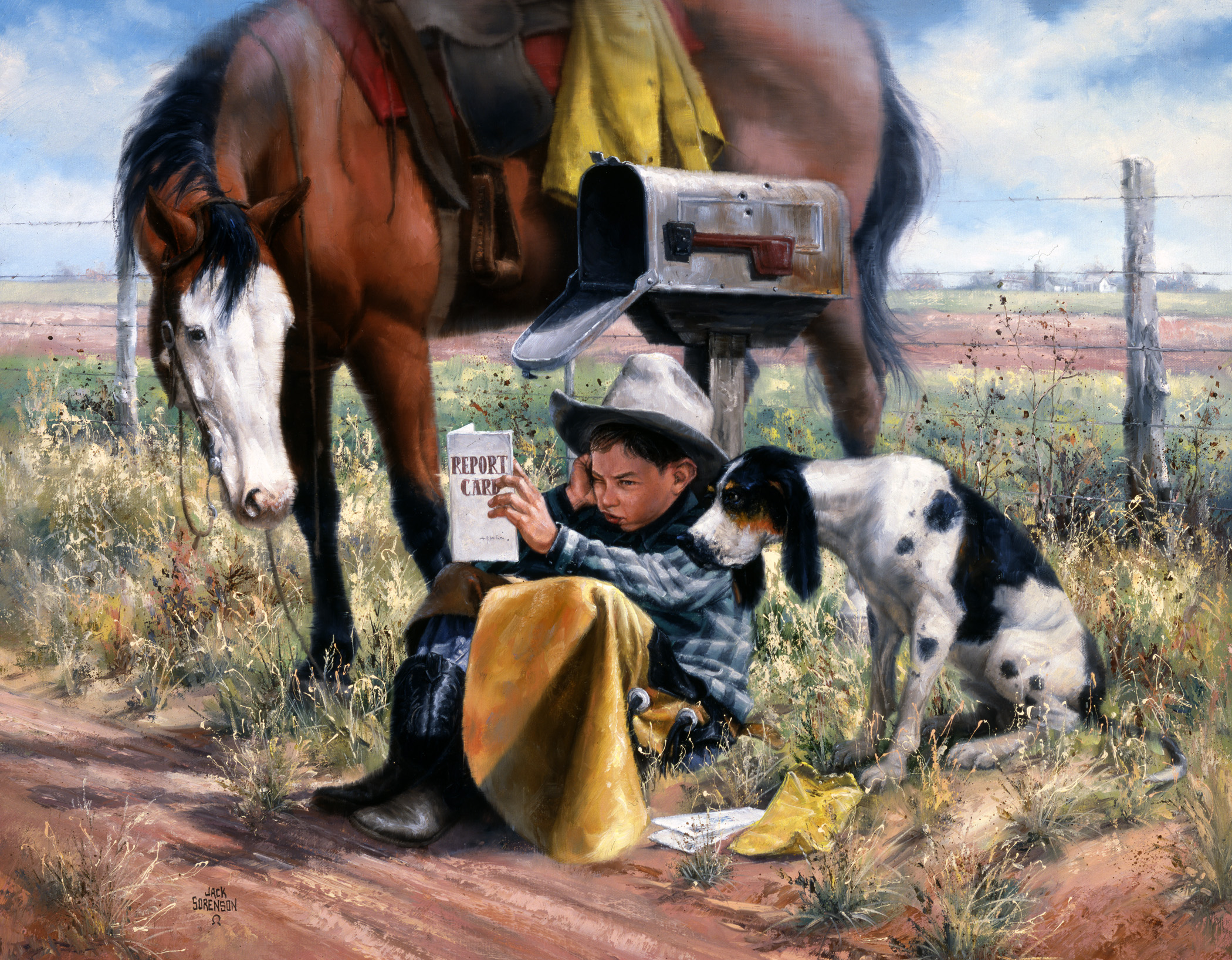

He could draw anything—and still can. But what young Sorenson loved to draw most was what he was surrounded by growing up, his dad being a rancher: that was horses.

“My dad used to train cutting horses,” he said. “The guys that own the horses he was training would always want my sketches of their horses ’cause they love their horses.

“So I got to where I could draw a likeness of any horse.”

Inborn talent counts for much, but Sorenson was introduced to many teachers who helped develop his hand and his eye. One of the first and most influential was the late Oklahoma-based expressionist painter Dord Fitz when Sorenson was 21.

“He was a genius. He made me go down in the bottom of the canyon and he said, ‘I want you to paint every green, you see,’ and it was like 60-something different shades of green,” Sorenson said.

“I came up and I showed him that and he said, ‘Alright, now go back down there and cut half of them off; only give me the 30 that you see most often.’ And so [he] let me do that, then I had to cut it down to 12.

“Identify the value first. He says the color can be anything if you get the value right, and I’m not sure that’s totally true, but I understand what he was trying to say.”

Over the decades, he studied with 28 different Western artists—notably, Howard Terpning, whose paintings sell for up to a quarter million, Martin Greeley, and Bruce Green.

Of course, the greats of Western painting, Russell and Remington, are right up there in Sorenson’s books, Russel for his storytelling and Remington for his draftsmanship.

Both traits feature prominently in Sorenson’s own work.

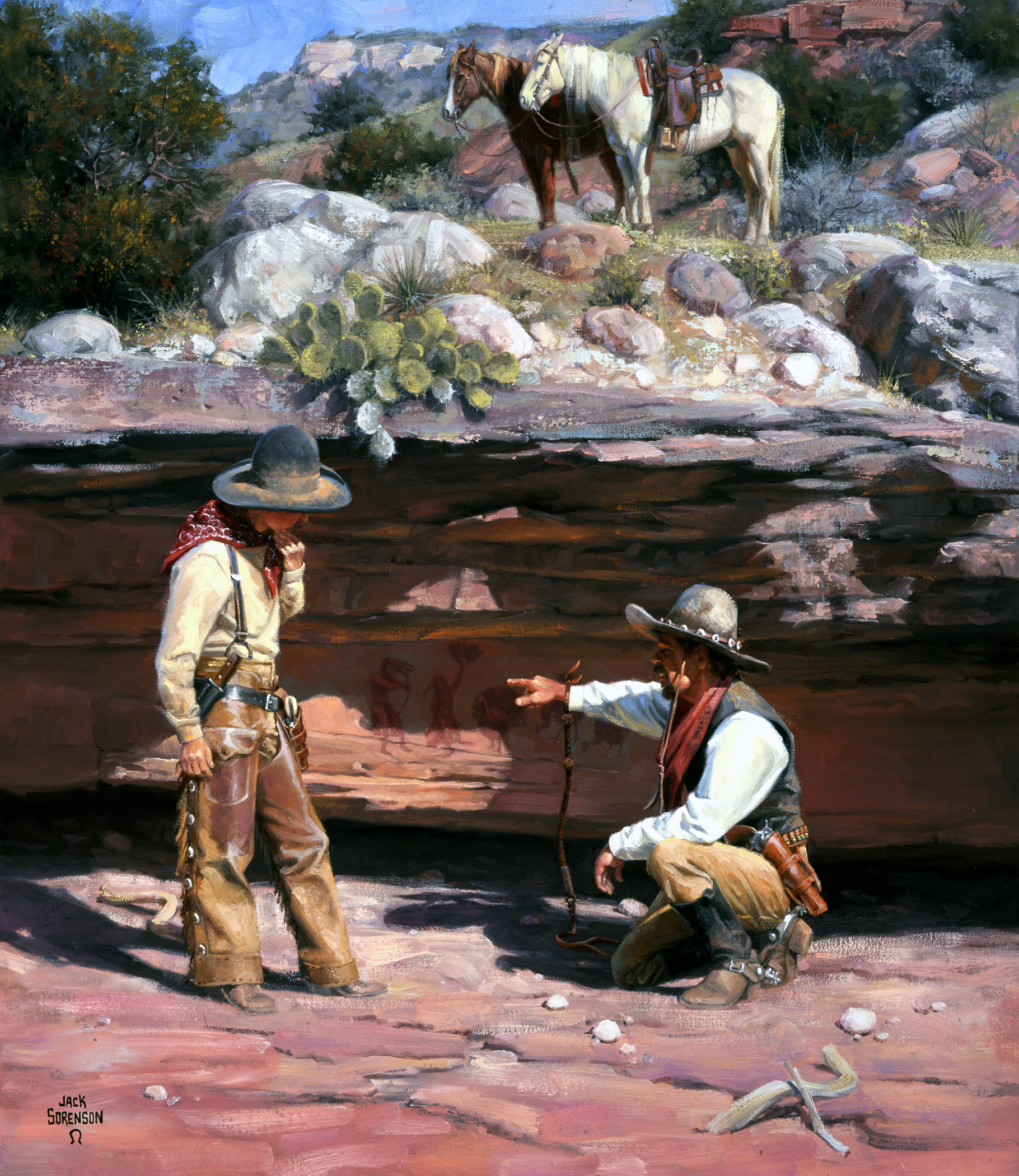

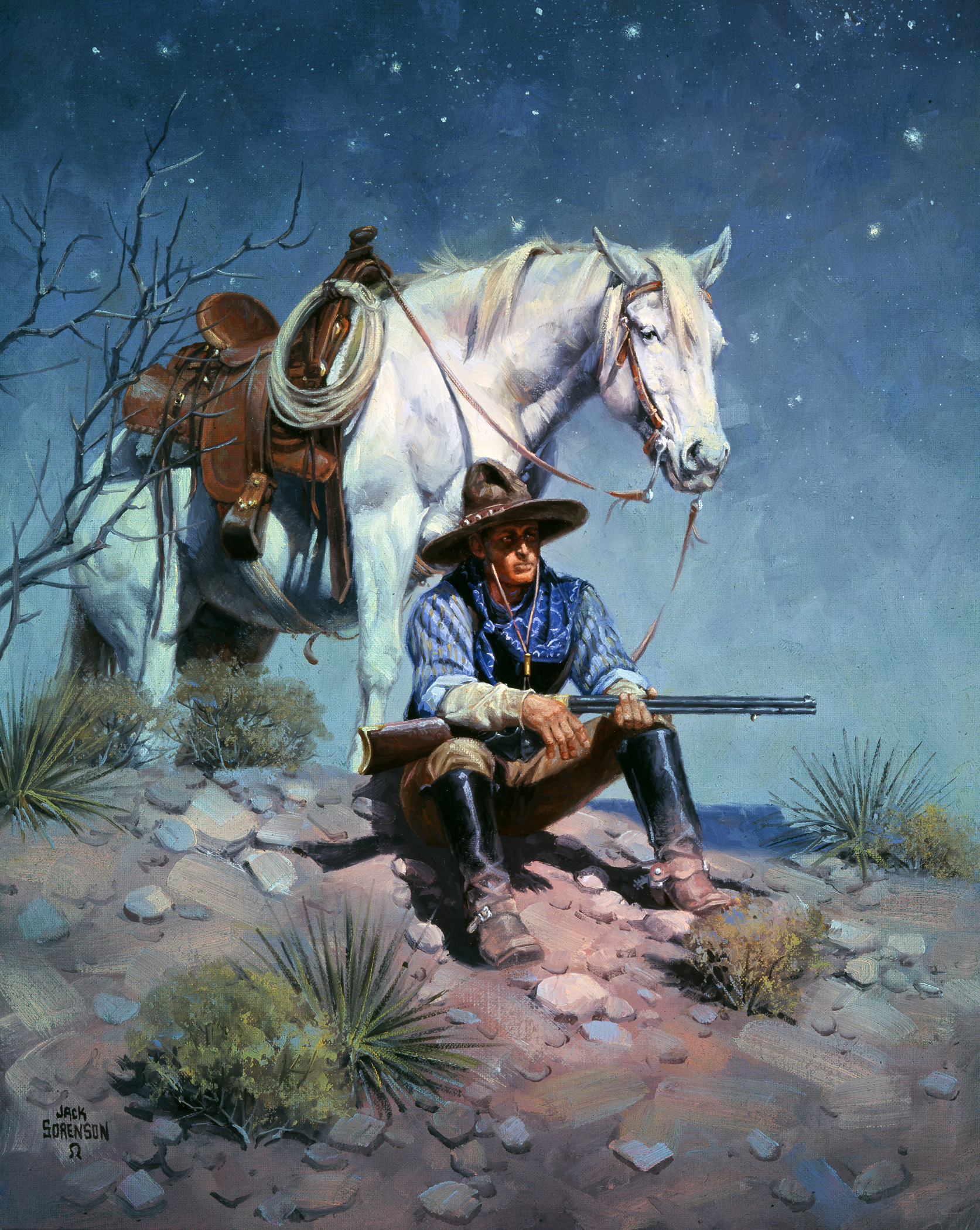

Perhaps because of his wide array of mentors, Sorenson developed a range of styles. He’s capable of the most meticulous realism, as expressed in his work “Easy to Come By, Hard to Get Away With,” depicting outlaws caught red-handed by a lawman.

“These guys have robbed the stagecoach and they have the strongbox,” the artist said. “And they’re being caught.”

Sorenson’s finely-rendered Old West scene stems from a love he developed from building frontier towns and driving stagecoaches in dramatic reenactments of cowboy gunfights—another aspect of his upbringing.

Of course, growing up watching “Gunsmoke” and “Rawhide” played into that Old West fascination.

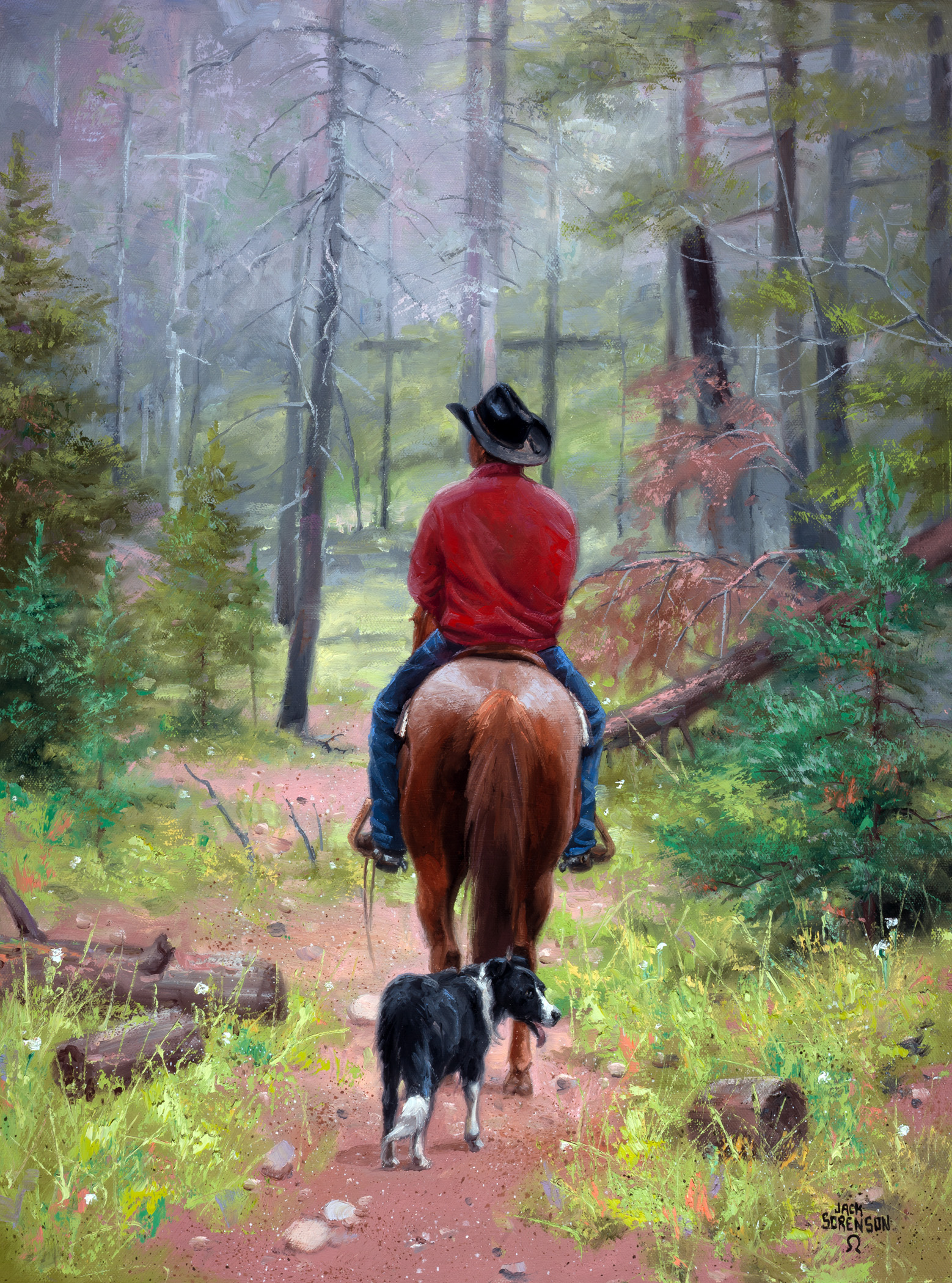

But, while commissions sometimes call for a tighter picture, Sorenson personally prefers to “paint fairly loose.”

“I’ve noticed the longer that I paint, the more I do loosen up,” he said. “It’s much more difficult to paint loose than it is tight because your negative space shapes are just as important as your positives.

“You have to be very conscious of every brushstroke, and I want everybody that looks at my paintings to feel like I was having fun.”

Befittingly, Sorenson prefers to work wet-on-wet (rather than over dried paint layers), applying a wash directly on white canvas while leaving visible brush marks. He regularly paints plein air (outdoors) to keep his color judgment sharp.

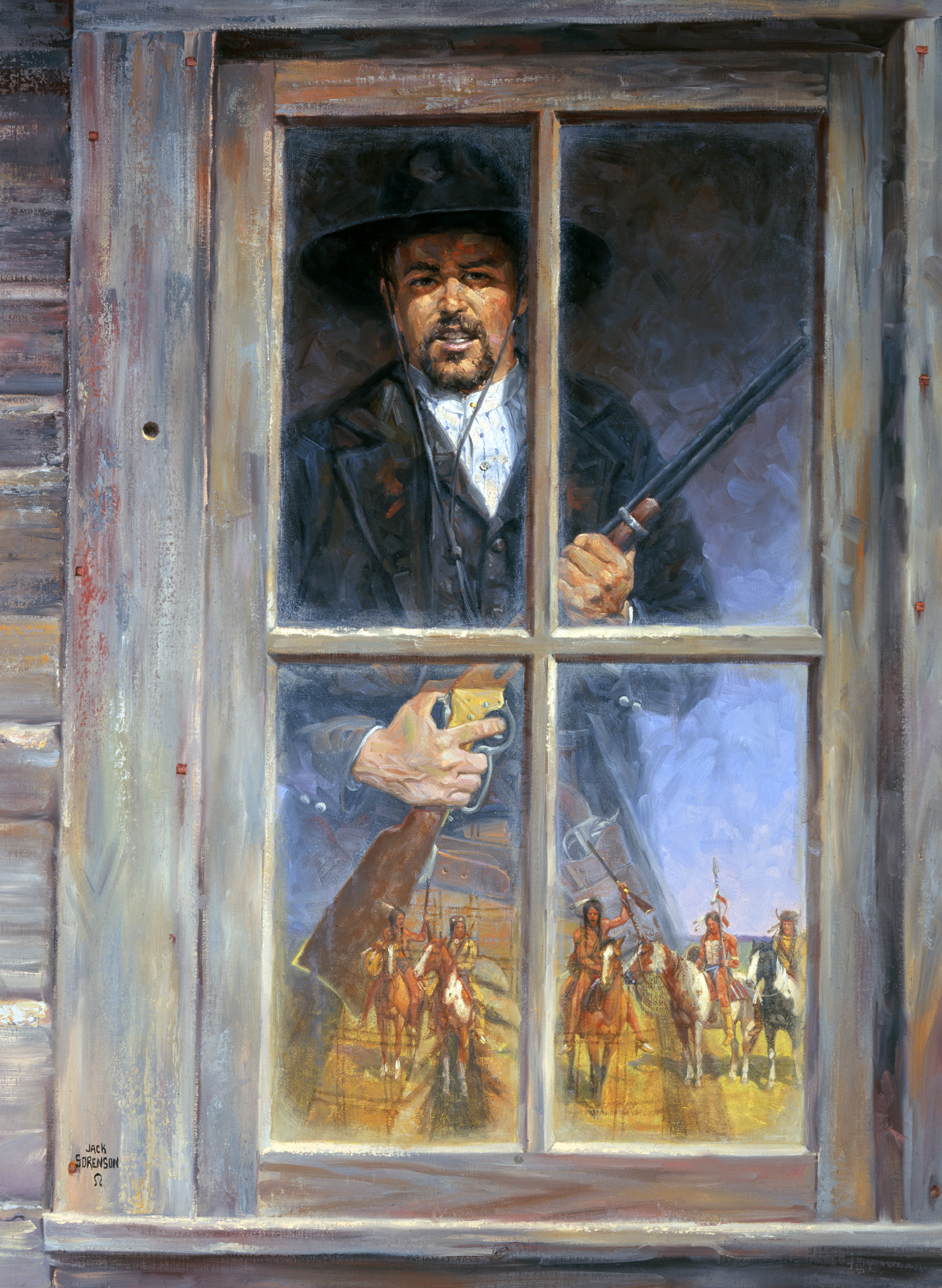

Exemplifying this “loose” manner, Sorenson portrayed Bass Reeves, the famous Oklahoman lawman in Indian territory, who also was a black man.

“He was one of the only black marshals but I was asked for a magazine to do a portrait of him,” Sorenson said, adding that his paintings have been featured on 90 magazine covers over his career.

Foremost of all, a painting has to have individuality—the stamp of the artist. Some artists paint “Kodak colors,” Sorenson said. Whatever you see in the photo ends up on the canvas.

“If you and I just copied a photograph, [the painting] wouldn’t tell anything about you any different from me,” Sorenson said. “That’s not art, in my opinion. You have to put your own stamp of individuality on everything.

“My horses have to look like horses—don’t misunderstand me—but I want them to look like my vision of horses.”

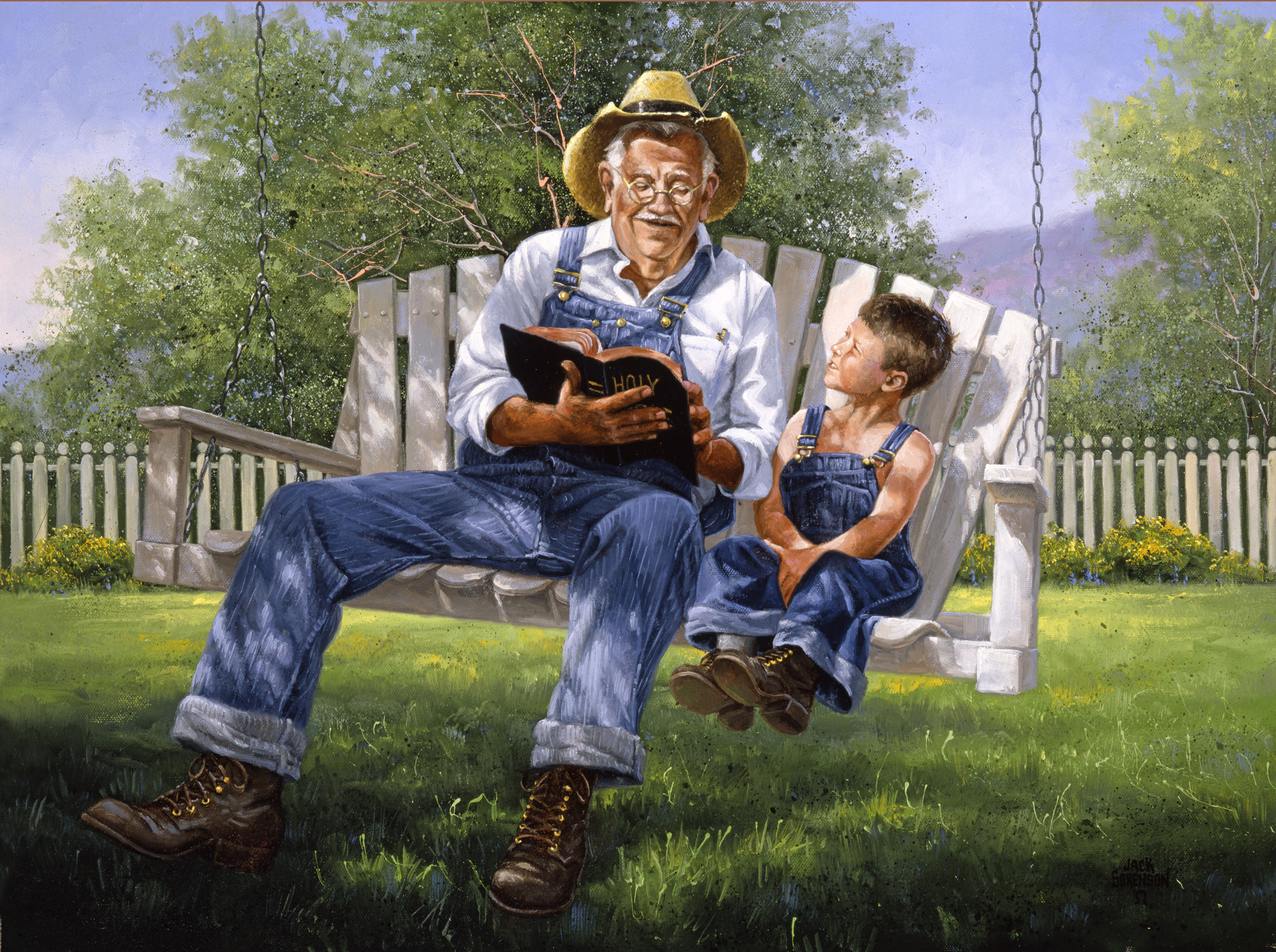

As for what his “stamp” entails, Sorenson said he aims to “spark a memory of someone that had a similar background” as him, adding, “I just feel like you have to evoke an emotion. That’s why stories are so important to me.”

But it’s more than that. To Sorenson, cowboys have always been “solid character guys,” and that’s a virtue that shines through in his artwork. “I’ve never known a cowboy where they just had low morals,” he said. “They all seem to have a moral standard to them.”

Share your stories with us at emg.inspired@epochtimes.com, and continue to get your daily dose of inspiration by signing up for the Inspired newsletter at TheEpochTimes.com/newsletter