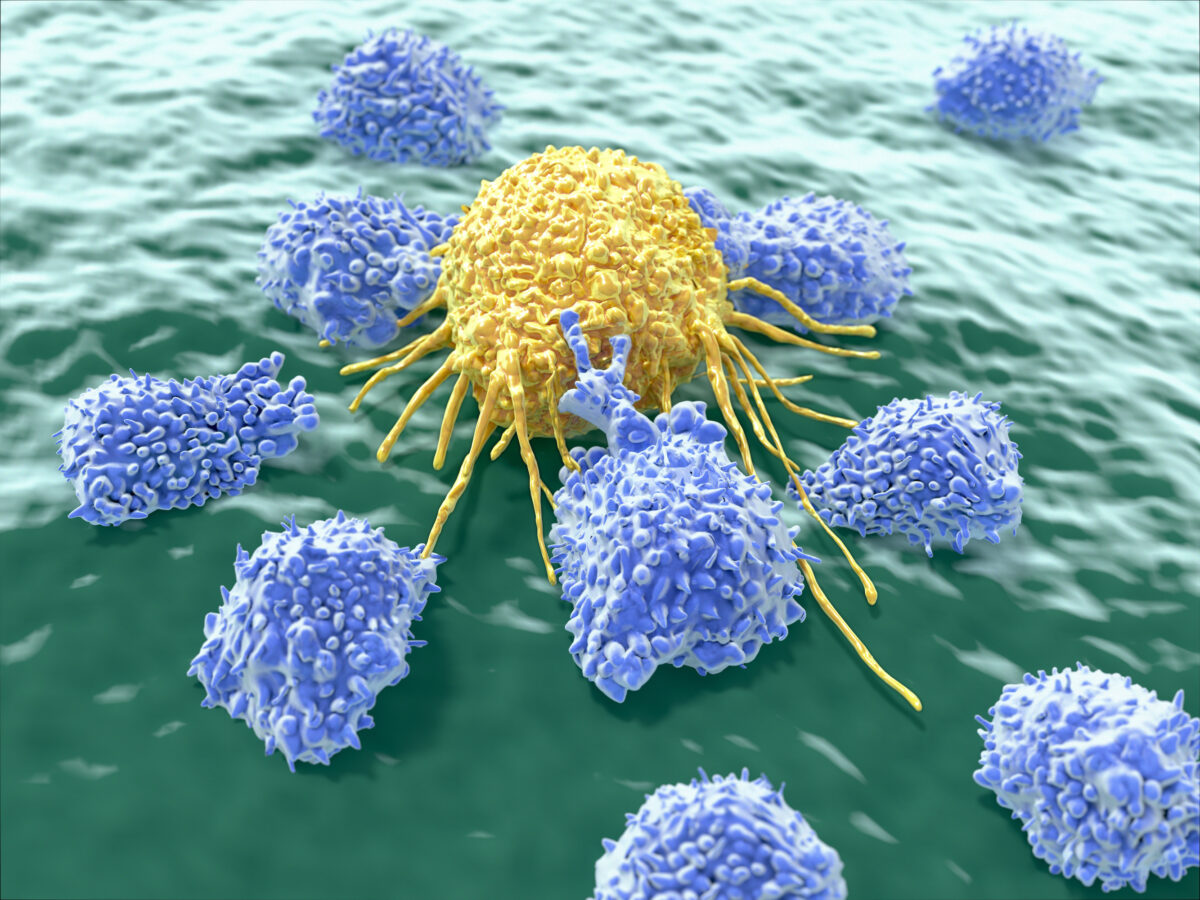

Yes, according to new research, where cancer cells were found to act as a ‘weapon’ against other cancer cells.

Known as dual-action therapy, this approach is created to eliminate existing tumours and train the immune system to kill new ones, thus preventing cancer recurrence.

This revolutionary new way to turn cancer cells into potent, anti-cancer agents has been developed by the lab of Khalid Shah, MS, PhD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system.

In their research, investigators developed a new cell therapy to eliminate established growths and induce long-term immunity, which helps train the immune system to prevent cancer from recurring.

The team tested their dual-action, cancer-killing weapon on a deadly brain cancer glioblastoma with promising results.

“Our team has pursued a simple idea: to take cancer cells and transform them into cancer killers and vaccines,” Shah said in a press release.

“Using gene engineering, we are re-purposing cancer cells to develop a therapeutic that kills tumour cells and stimulates the immune system to destroy primary tumours and prevent cancer.”

Brain cancer is a type of cancer that affects the brain or the spinal cord and can be very difficult to treat, often resulting in a poor prognosis.

Worldwide, an estimated 251,329 people died from primary cancerous brain and Central Nervous System tumours in 2020.

The symptoms of brain cancer include:

· Headache – which does not subside from over-the-counter medication

· Weakness in the limbs, face, or one side of the body

· Impaired coordination

· Difficulty while walking

· Difficulty in routine activities like reading and talking

· Noticeable changes in senses like taste and smell

· Bladder control problems

· Changes in mood, personality, or behaviour

· Nausea or vomiting

· Memory loss

The exact causes of brain cancer are not known, but a few of the possible causes are:

· Genetic mutations cause uncontrolled multiplication of cells in the brain, which results in a tumour mass.

· Cancer in other parts of the body.

The risk factors include:

· Family history

· Age – elderly people are at higher risk of developing tumours

· Exposure to chemicals and radiation

Currently, there are a few treatments available for this disease, including surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, but they are not always effective and can have significant side effects.

A potential solution to this issue is a cancer vaccine, a type of therapy that uses the body’s immune system to fight cancer.

It works by training the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells.

Several cancer vaccines are currently in development, but none have been approved for treating brain cancer.

The approach that Shah and his colleagues have taken possesses a unique feature, where instead of the usual approach of using inactive tumour cells, the team re-uses live tumour cells, which travel across the brain to return to the site of their fellow tumour cells.

Taking advantage of this unique property, Shah’s team engineered living tumour cells using the gene-editing tool CRISPR-Cas9 and re-purposed them to carry and release an agent that kills the tumour cells.

In addition, these engineered tumour cells were designed to make it easy for the immune system to spot, tag and remember them, preparing the immune system to have a long-term anti-tumour response.

Those re-purposed therapeutic tumour cells (or ThTC) were tested in different mice lines, including the one that had bone marrow, liver and thymus cells derived from humans, mimicking the human immune microenvironment.

Shah’s team also built a two-layered safety switch into the cancer cell, which, when activated, eradicates ThTCs if needed, which makes this dual-action cell therapy safe, applicable, and efficacious in these models, suggesting a roadmap toward treatment.

While further testing and development are needed, Shah’s team specifically chose this model and used human cells to smooth the path of applying their findings to patients.

“Throughout all of the work that we do in the Center, even when it is highly technical, we never lose sight of the patient,” says Shah.

“Our goal is to take an innovative but translatable approach so that we can develop a therapeutic, cancer-killing vaccine that ultimately will have a lasting impact in medicine.”

Reverse-engineered therapeutic tumour cells (ThTCs) refer to cancer immunotherapy involving taking a patient’s tumour cells, genetically modifying them in a laboratory, and re-injecting them back into the patient, an approach also known as “autologous tumour cell immunotherapy.”

The ThTCs process involves using techniques such as CRISPR gene editing to modify the tumour cells to enhance their ability to stimulate the immune system and to make tumour cells more visible to the immune system so that the immune system can recognize and attack the cancer cells more effectively.

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is a gene-editing technology that allows scientists to modify or manipulate genes with precision and accuracy. It uses a protein called Cas9, which can be programmed to target specific genes and cut them at specific locations in the DNA.

However, it is also considered controversial, with critics of the technology concerned it could be used to create DNA-based vaccines that would alter the human genome.

Dr. Kiran Musunuru, in his book, “The CRISPR Generation: The Story of the World’s First Gene-Edited Babies”, called the technology a double-edged sword.

Read More

Musunuru is an assistant professor in Harvard’s Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology and a cardiologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“The work we’re doing does have consequences,” Musunuru said. “It’s not happening isolated in a laboratory. Increasingly, the work that we’re doing has implications for human health and well-being, and when used irresponsibly, can cause harm. The scientific community needs to be more mindful of that.”

Musunuru compares CRISPR gene editing to fire. Use it right, and it can be very helpful. But cross the line, and you can spark a raging inferno.