The Bank of England (BoE) has hiked interest rates from 4.5 percent to 5 percent, a more aggressive jump than previously expected.

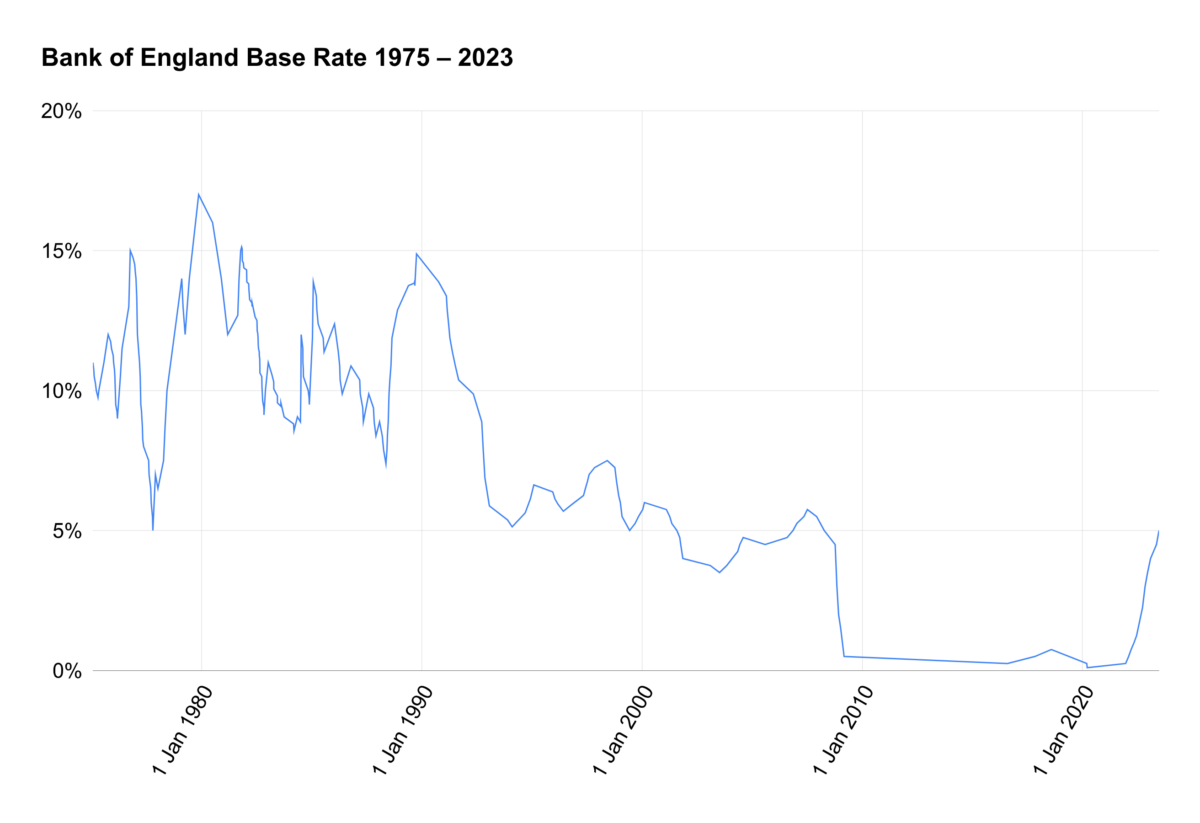

It’s the 13th consecutive rate increase in 18 months, and this level was last seen in April 2008 before the central bank began slashing rates during the financial crisis.

The BoE was previously expected to raise bank rates to 4.75 percent, where it was predicted to peak, but after Wednesday’s figure showed core inflation stuck at 8.7 percent in May, traders have anticipated a surprise 0.5 percent jump on Thursday and a peak of 6 percent early next year.

Seven members of the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted to increase bank rates to 5 percent as inflation pressure from the wage-price spiral is “likely to take longer to unwind than they did to emerge,” the MPC said.

The other two MPC members preferred to keep it at 4.5 percent, arguing that lowered energy prices would ease inflation and that the lags in the effects of monetary policy meant that the impact of previous rate hikes was still to come through.

The MPC also warned that further increases will be coming “if there were to be evidence of more persistent [inflationary] pressures.”

BoE Governor Andrew Bailey said the bank has “got to deal with” inflation, which is still much higher than the bank’s 2 percent target.

“We know this is hard—many people with mortgages or loans will be understandably worried about what this means for them,” Bailey said.

“But if we don’t raise rates now, it could be worse later. We are committed to returning inflation to the 2 percent target and will make the decisions necessary to achieve that.”

Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt voiced support for the bank’s decision, saying, “High inflation is a destabilising force eating into pay cheques and slowing growth.”

“Core inflation is higher in 14 EU countries and interest rates are rising around the world, but the lesson from other countries is that if you stick to your guns, you bring inflation down,” he said.

“Our resolve to do this is watertight because it is the only long-term way to relieve pressure on families with mortgages. If we don’t act now, it will be worse later.”

Labour Party leader Keir Starmer said the economic state is a “genuinely difficult place for the opposition.”

Asked whether a recession is inevitable, Starmer told a CEO summit hosted by the Times of London, “I hope not.”

“This is genuinely a difficult place for the opposition, because you may all think, ‘well, it’s good for the opposition if the economy isn’t working very well because it provides an opportunity for the electorate to look somewhere else,'” he said.

“But the pain of this, obviously, is with working people or families across the country, and I don’t want to see that pain.”

Rising interest rates have put significant pressure on mortgage holders. According to estimates by the Resolution Foundation, average household remortgaging would cost an extra £2,900 next year. The Institute for Fiscal Studies warned on Wednesday that 1.4 million people could lose 20 percent of their disposable income to rising mortgage payments.

The chancellor is set to meet lenders on Friday to ask how they can help borrowers struggling to pay their mortgages, but Labour has said the party would force lenders to help if it was in power.

Shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves ruled out subsidising mortgage holders, telling BBC Radio 4’s “Today” programme that “a big fiscal injection of cash into the economy, especially an untargeted injection, would not be the right approach.”

Under Labour’s five-point plan, banks would have to wait for at least six months before starting repossession proceedings, and they’ll have to allow any changes to be reversible, unlike under the current situation where borrowers can be trapped in less favourable terms.

The financial regulator would also be told to issue guidance, telling banks that borrowers’ who ask for help won’t have their credit scores affected.

But Tom Clougherty, research director of think tank the Centre for Policy Studies, told the BBC that Labour’s plan “mostly ‘requires’ lenders to do a variety of things they will already be doing voluntarily,” and that forcing them to do more will increase costs for borrowers and “cause as many problems as it solves.”

The Liberal Democrats have called for an emergency “Mortgage Protection Fund” to subsidise struggling mortgage holders.