Strep A is commonly known to cause mild bacterial infections such as strep throat and impetigo, yet more invasive and deadlier forms of the bacteria are on the rise. Recently, several countries—including the United States—observed an unusual increase in cases of both invasive Strep A and scarlet fever compared with pre-pandemic times. Meanwhile, antibiotics commonly prescribed to treat Strep A are experiencing unusual shortages.

Also known as Group A Streptococcus or GAS, Strep A is a group of bacteria that causes various diseases, most commonly strep throat and impetigo. It is estimated that there are around a combined 700 million worldwide and half a million deaths. In general, a strep A infection comes with a few generalized symptoms, including a sore throat, a rough rash, scabs or sores, pain and swelling, muscle aches, and so on.

Let’s zoom in on some of them. Impetigo, also known as a school sore, is caused by Strep A and forms a yellow scab or crust as the sore heals. It tends to be quite itchy and gnarly looking, but will usually go away after a few days.

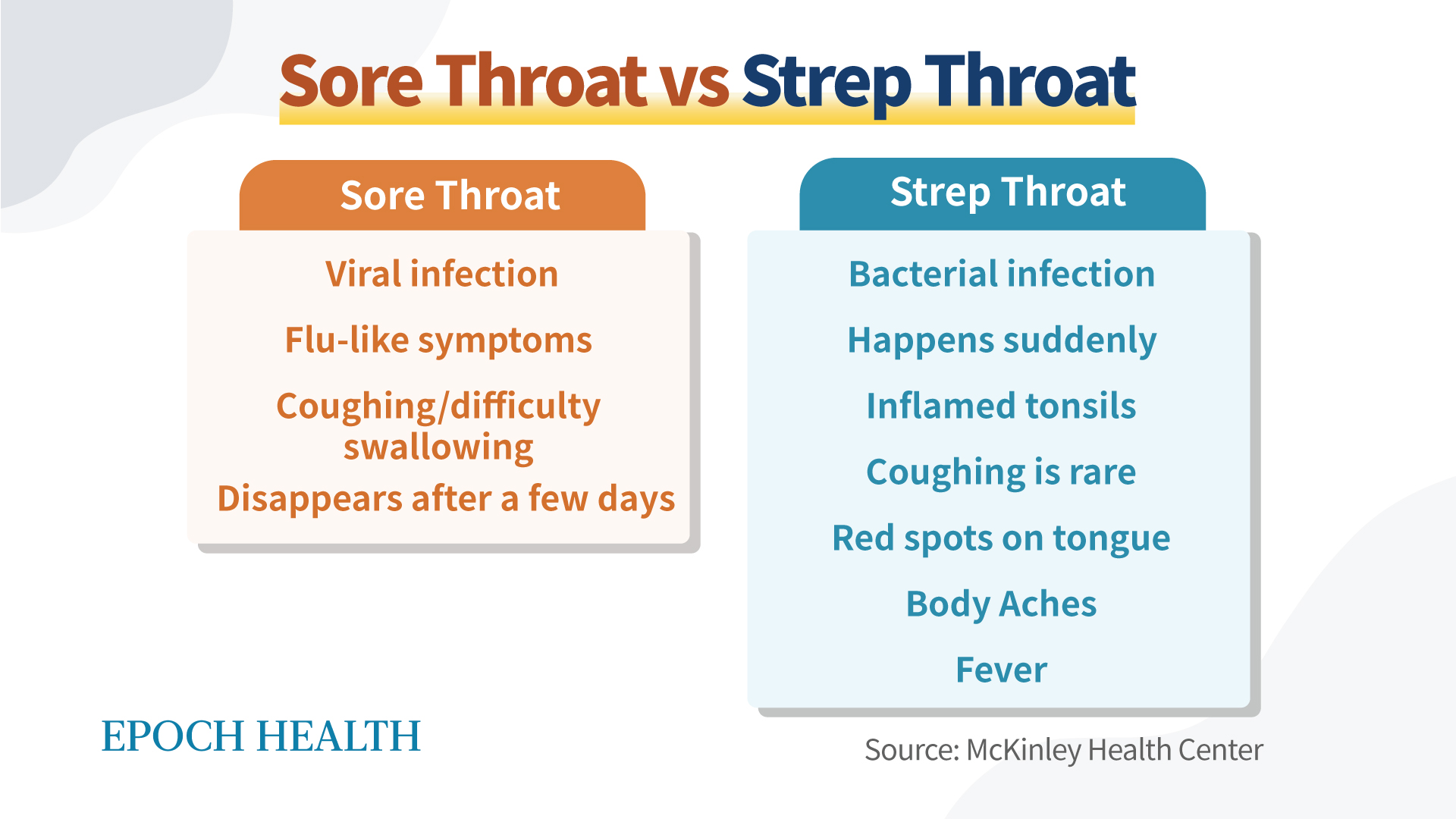

Strep throat, however, allows for a lot more variation. The most common symptoms include fever, a sore throat, red cheeks, white patches on swollen tonsils, and so on. Strep throat, despite having similar symptoms to the flu, is caused by bacteria instead of a virus. People who are elderly, have skin issues (such as blood deprivation or breakdown), or have chronic medical conditions such as diabetes are at increased risk. Each year in the United States, Strep A causes approximately 5.2 million cases of strep throat, 14,000 to 25,000 invasive infections, and 1,500 to 2,300 deaths, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Strep throat can develop into a severe type of illness called scarlet fever. Scarlet fever, also known as scarlatina, is due to the unhealthy progression of a strep throat infection. It is most common in children 5 to 15 years of age and causes a vivid rash across the patient’s entire body—hence the name, “scarlet fever.” It commonly causes a high fever, strawberry red tongue, and muscle aches in addition to the swollen lymph nodes and difficulty swallowing that come with strep throat.

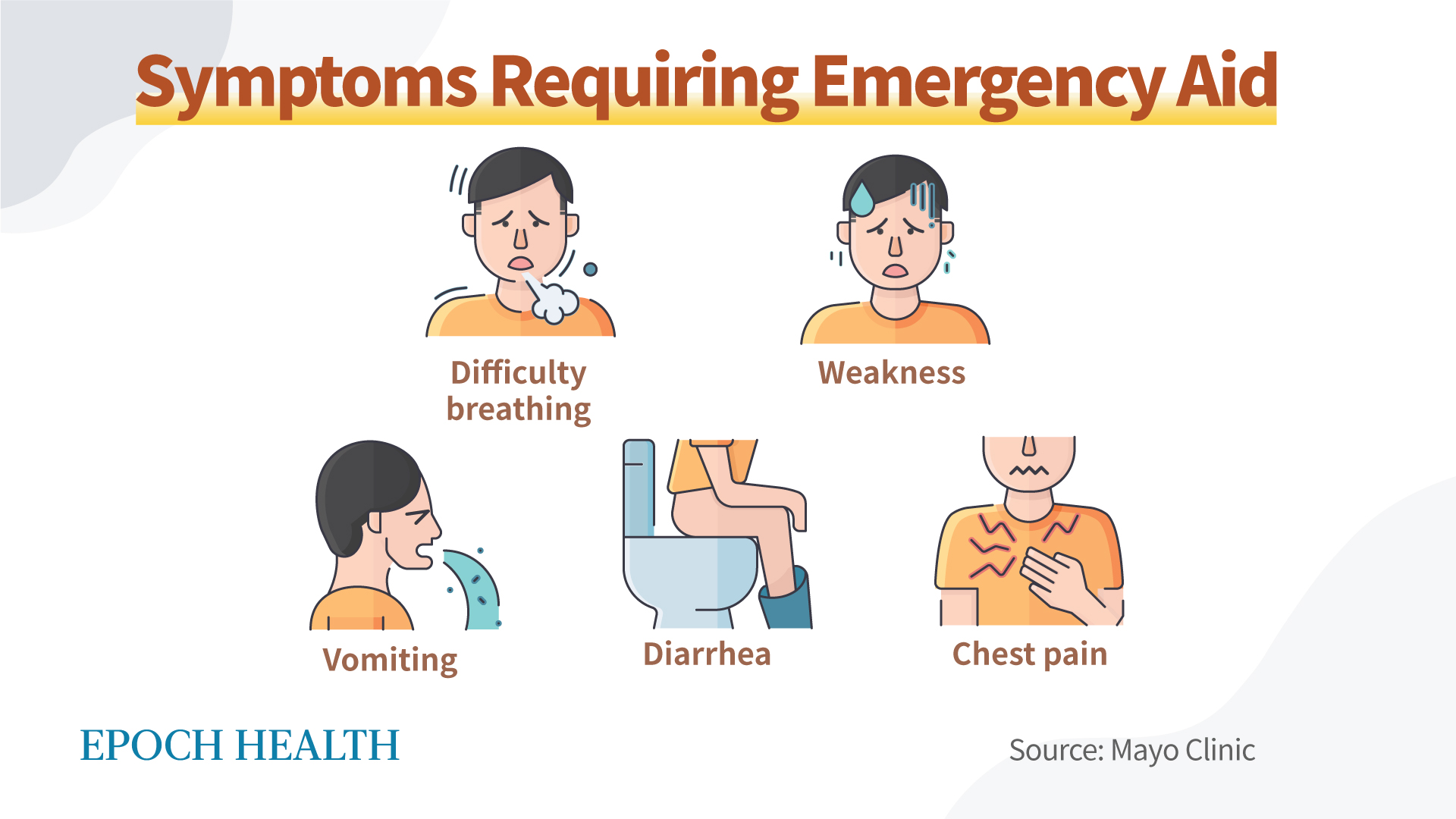

In general, all Strep A-induced diseases are treated with antibiotics, yet there are some symptoms you should watch out for in scarlet fever that require immediate medical attention. These include difficulty breathing, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, or chest pains. It is commonly better to seek medical attention sooner than later as the progression of the disease is difficult to predict.

This is, unfortunately, not the end of the story when it comes to Strep A. These gram-negative bacteria are also known for causing Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome—which results in low blood pressure and multiple organ failure—and necrotizing fasciitis as well, also known as flesh-eating bacteria. Early symptoms of flesh-eating bacteria include a red, warm, or swollen area of the skin that spreads quickly, as well as severe pain. It often includes a fever during the early stages. Later on, the skin may change color as pus, ulcers, blisters, or black spots begin to emerge on the infected area.

These drastically more severe forms of Strep A are caused by invasive Group A strep. The prevalence of invasive Strep A is also on the rise.

Strep A is on the rise on an international scale, affecting children under 10 the most. Invasive forms of Strep A are a serious issue to reckon with. Invasive Strep A is when the pathogen has reached parts of the body where bacteria are usually not found, such as the blood, deep muscle and fat tissue, or the lungs. For instance, Strep A may infect an open wound and exploit the openings in the skin to literally churn through the flesh and cause severe damage in a short period.

Disease progression can be extremely fast. In one case, a 5-year-old from the UK infected with the bacteria was taken to the hospital rather quickly. Three days after being diagnosed and admitted to an intensive care unit, the girl passed away. Her case was unfortunately not a rare incident.

Usually a mild Strep A infection can be treated at home with plenty of rest and fluids. However, for the more severe forms of the disease, antibiotics are required. The antibiotics of choice for treating Strep A are amoxicillin and penicillin, yet there has recently been a major shortage of amoxicillin reported by multiple pharmaceutical companies.

In the past, doctors usually used erythromycin and azithromycin to treat strep throat, particularly in those allergic to penicillin. However, the rising resistance to erythromycin and other macrolides, as well as to clindamycin, has changed the landscape of antibiotics.

In fact, the percentage of invasive Group A Streptococcus (GAS) infections that are resistant to erythromycin has nearly tripled (pdf) in eight years. In the six years between the CDC’s first Antibiotic Resistance (AR) Threats Report in 2013 (pdf) to the latest report in 2019, GAS infections increased by 4,100 while deaths increased by 290. The treatment level of GAS is currently considered “concerning.”

More doctors are having to use amoxicillin for treatment due to the rise of erythromycin-resistant Strep A infections. However, a survey conducted in early February 2023 showed that the nationwide amoxicillin shortage—which was brought to the public’s attention in November 2022—is ongoing, as 73 percent of the survey’s participants reported a shortage of the antibiotic in their workplaces over the last 45 days.

One of the main reasons for the shortage of amoxicillin was the supply chain disruptions during the COVID pandemic. Therefore, in the aforementioned survey, 9 in 10 respondents believed that the government should place a greater emphasis on manufacturing and distributing amoxicillin here in the United States, as opposed to procuring it from abroad.

“This country really needs to put more attention on securing health care needs for our citizens,” one pharmacist surveyed said. “Without the ability to acquire even the most basic of medications, how can patients have security in knowing we can help them with more complicated issues?”

Full domestic production of amoxicillin would cost anywhere from 5 to 10 percent more than if the United States acquired it from overseas, but more than 90 percent and 70 percent of pharmacists, respectively, somewhat or strongly agreed that a slight hike in price is well worth paying for such an essential medication—especially in the United States, where the money our country spends every year on health care exceeds 4 trillion dollars.

This over-reliance on foreign medicine supply chains has become a national security issue. Many antibiotics used to be made in the United States, but by 2019, 80 percent of the medical industry’s active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for drugs like amoxicillin came from overseas, the majority of which were traceable to China or India.

According to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s report, China now accounts for 95 percent of ibuprofen imports, 91 percent of hydrocortisone imports, 70 percent of acetaminophen imports, 40 to 45 percent of penicillin imports, and 40 percent of heparin imports.

If the Chinese communist regime is the primary adversary of the United States in terms of national security, isn’t it a devastating existential threat that we rely so heavily on it for our basic medicine supply? Dr. Rosemary Gibson wrote a wonderful book, “China RX: Exposing the Risks of America’s Dependence on China for Medicine.” It is definitely a must-read for people in the field of national security.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times. Epoch Health welcomes professional discussion and friendly debate. To submit an opinion piece, please follow these guidelines and submit through our form here.