Many people know Alexander Hamilton as the man whose face is on the 10-dollar bill, but many do not know why. Even though he was never a president like George Washington on the one-dollar bill or Abraham Lincoln on the five, Hamilton’s contributions in the nation’s early years earned him the nickname the “Father of American Capitalism.”

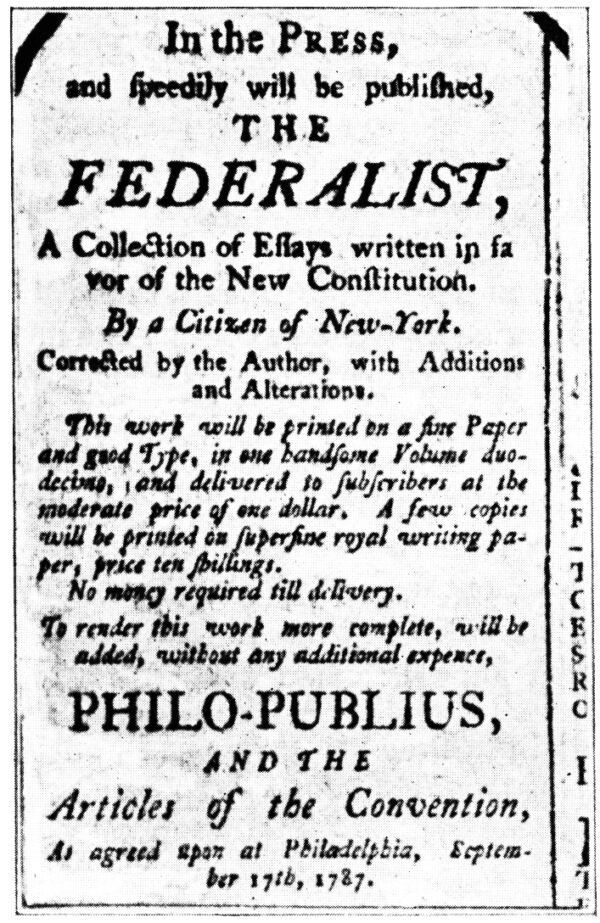

Hamilton is considered one of the nation’s founding fathers due to his work during the American Revolution and the fact that he authored several of “The Federalist Papers” that helped the U.S. Constitution get ratified. He gained much of his fame as the founder and inventor of the U.S. financial system that is still in place to this day.

Coming from a different background than many of the nation’s founding fathers, Hamilton used his political connections and experience to establish the country once he became the first secretary of treasury under President Washington. Although his views saw great opposition, which led to him to develop several enemies, his economic policies helped the nation turn into a strong economic power on the global stage in the 19th century, after his death.

According to several sources, historians seem to disagree on the year Hamilton was born. Most agree that Hamilton was born in 1757, but speculation came about in the 1930s when a 1768 probate paper from the Caribbean island of St. Croix was published that listed him being 13 years old that year. This would have meant he was born in 1755.

Hamilton was born in Charlestown on the island of Nevis, in what is now the West Indies, to Rachel Faucette and James Hamilton who were not married at the time. Since he was an illegitimate child, he was denied an education by the Church of England; instead, he was taught by the headmistress of his mother’s school. He also educated himself by reading around 30 books that were in his family library.

Hamilton’s father abandoned the family in 1766, and his mother died of yellow fever in 1768 making him an orphan. As a child, Hamilton went to work at a young age selling goods on the island until his writing skills caught the attention of his community.

In 1772, Hamilton wrote a letter to his father that contained a detailed account of a hurricane that struck Christiansted in St. Croix. Leaders in his community were so impressed that they raised funds to send Hamilton to the North American colonies to receive an education.

Hamilton briefly attended King’s College in New York, which is now Columbia University. There, he became heavily involved in the Revolutionary cause by writing pamphlets like “A Full Vindication of the Measures of Congress.”

Hamilton’s tenure at the college ended once the Revolutionary War broke out, and he was needed on the battlefields. He held several leadership positions in the Continental Army and was even recruited for Gen. George Washington’s staff.

In 1781, Hamilton became frustrated with the Washington and left his staff. But later that year, the general gave Hamilton a field command, and he successfully led an assault against British soldiers during the Battle of Yorktown, which led to the surrender of Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis during the war’s last major land battle.

In 1782, Hamilton resigned from the army and returned to New York where he educated himself and, after six months, passed the bar exam to become a lawyer. In the fall of that same year, he was appointed as a New York representative to the Congress of the Confederation.

For the next several years, Hamilton campaigned for the ratification of the Constitution. He, with help from John Jay and James Madison, published “The Federalist Papers,” a series of essays written to defend and promote the proposed U.S. Constitution. In fact, Hamilton wrote 51 out of the 85 essays that were published in various newspapers in 1787 and 1788.

In 1789, when Washington was elected the new nation’s first president, he appointed Hamilton as the secretary of treasury due to the relationship Washington had built with him during the war. Hamilton previously founded the Bank of New York and had used his experiences in the commercial shipping industry to become, as the American Library Association describes, “a brilliant, self-taught economist.”

As soon as Hamilton joined President Washington’s first cabinet, he quickly went to work to fix the nation’s economy that was in dire condition after the Revolutionary War. Governing bodies at every level in the country had taken on debts to fund the war effort and, as USHistory.org states, “the commitment to pay them back was not taken very seriously.” Each state’s IOUs to pay back the money that was borrowed to finance the war was basically deemed worthless.

Hamilton came up with a courageous plan for the federal government to pay off all debts incurred by the states: His plan was to issue new securities bonds to investors and create a revenue system comprised of customs duties and excise taxes. “The debt of the United States … was the price of liberty,” the U.S. Department of the Treasury website quotes him saying. Hamilton’s plan helped the nation form a stronger central government and it gave the nation more credibility on the world economic stage.

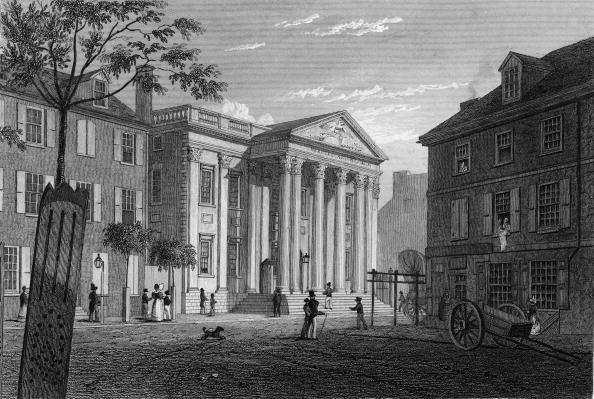

Hamilton then decided to develop the First Bank of the United States using the Bank of England as a model to further support a strong financial structure for the country. The bank held all of the government’s funds, increased capital to aid financial growth, and issued loans to the federal government.

The bank also issued the nation’s first paper currency so that it was able to get rid of the currency from individual states that had varying values. Hamilton then came up with plans for the United States Mint that was eventually established in 1792.

However, Hamilton’s ideals of the nation having a strong central government saw much opposition from other leaders at the time, including Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson and others thought that Hamilton’s nationwide bank and many of his other policies were designed to turn the United States into a monarchy, and take away power from the states.

During that era, the nation had been dependent on the export of agricultural goods to fund imports of manufactured goods from overseas. Hamilton wanted American manufacturers to be more self-sufficient and he believed that a strong manufacturing sector would help the U.S. economy. He felt that the nation’s dependence on expensive imported goods inhibited financial growth.

He implemented a program that gave financial subsidies to American manufacturers to help them compete with goods imported from other countries. He also imposed tariffs or taxes on imported goods to promote the local manufacturing of products.

After the Revolutionary War, smuggling and pirating off the coast became a major issue due to a lack of shipping controls. In order to implement his tariffs, Hamilton knew that he needed some way to enforce the new taxes and help control the problems the United States faced with shipping.

Hamilton proposed an idea to congress to implement a naval police force on the shores of the country to help enforce the new taxes and regulations as well as control the nation’s shipping industry. In 1790, Congress officially established the Revenue Cutter Service which put armed “cutters” on the shores of the U.S. coast from Georgia to New England. The Revenue Cutter Service eventually turned into the United States Coast Guard.

Hamilton resigned from his post as the secretary of treasury in 1795, but he still remained involved in politics. During the presidential election of 1800, Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied, sending it to a vote in congress.

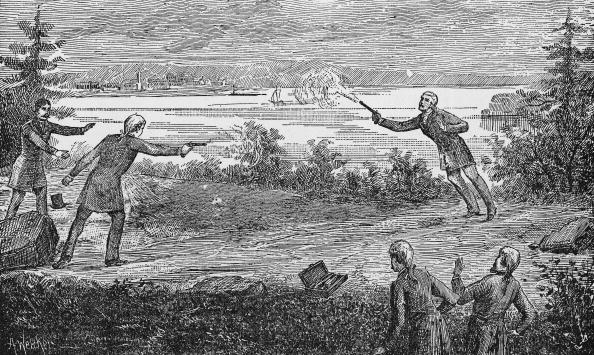

Hamilton helped persuade Congress to vote for Jefferson, causing Burr to lose the election. In 1804, Burr ran for the governor of New York, but failed. After being frustrated due to his losses, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel after hearing that Hamilton had insulted him at a dinner party.

Hamilton and Burr met on July 11, 1804 in Weehawken, New Jersey, to settle their differences in a duel. Most accounts say that Hamilton fired first, but his bullet hit a tree limb above his opponent. Burr fired second and hit Hamilton in the stomach just above his right hip.

Hamilton died soon after from his injuries, and many historians say that he actually missed Burr on purpose in memory of his son who died in a duel protecting his father’s name.