When social activists and ideologically driven historians claim something is evil by virtue of its existence, chances are those who receive that information are missing context. Typically, a lot of context.

The idea of colonialism is one of those topics in which today’s social and political commentators are missing a lot of context, though indeed they are not short on rhetoric. Bruce Gilley, the professor of political science at Portland State University, has written a new book on the subject in an effort to provide more context on colonialism, though he does add his own hyperbolic rhetoric to the mix.

“In Defense of German Colonialism: And How Its Critics Empowered Nazis, Communists, and the Enemies of the West” is a follow up to his work on imperialism, entitled “The Last Imperialist: Sir Alan Burns’ Epic Defense of the British Empire.” Both works are hyper-specific as one centers on an individual, Burns, though it does extrapolate to the idea and ideals of the British Empire, and the other centers on a country, Germany.

This work, as the title notes, is a defense of an era that has been misconstrued, and it’s justifiable to suggest that it has been misconstrued on purpose. Gilley takes advocacy to task by the use of historical records. Of course, advocacy has its place in the world, but not if it is done for political ends; and this is the problem―and it is a very destructive problem―that Gilley works to dissect and lay bare. This is what Gilley tries to differentiate in his book.

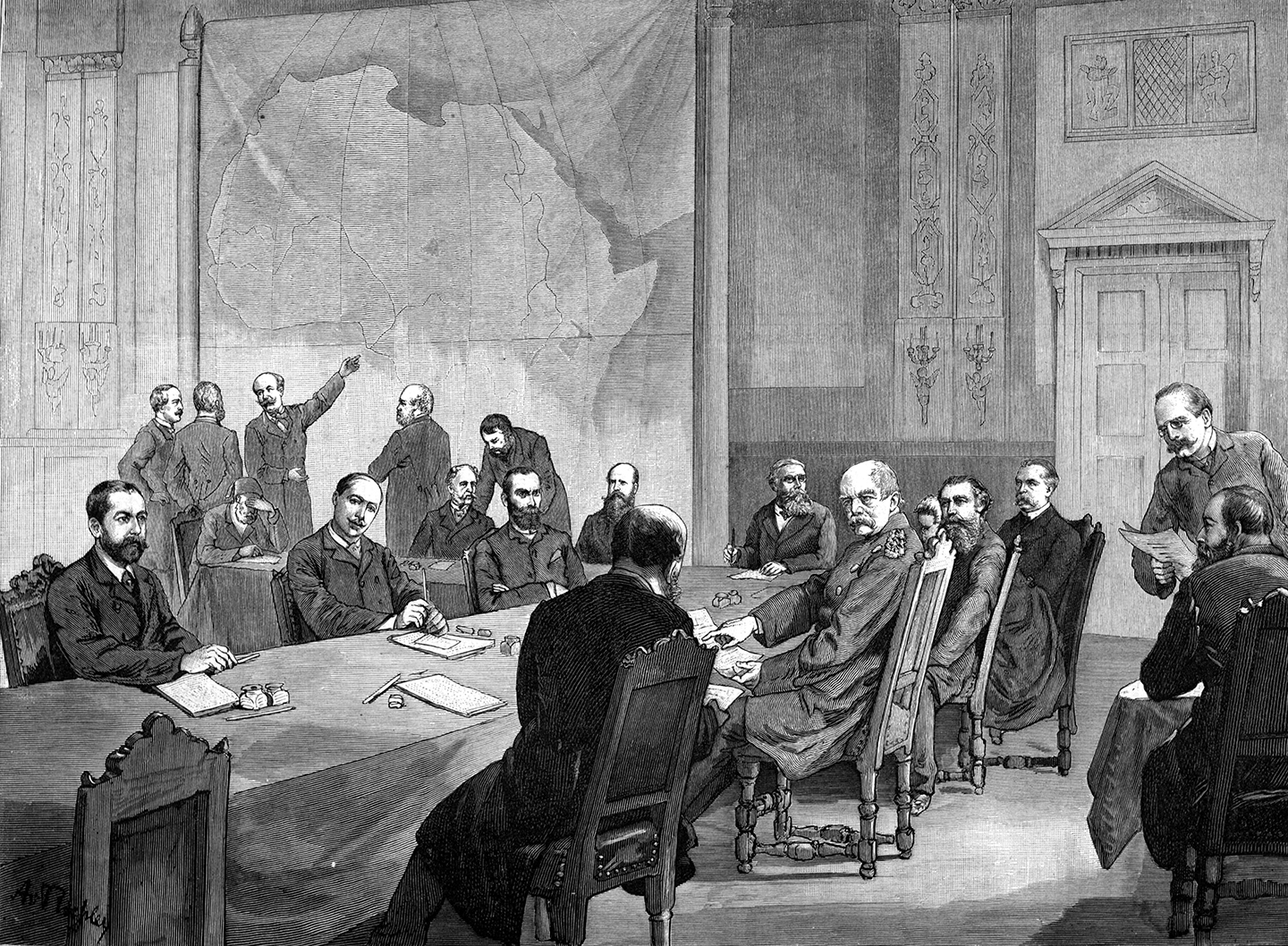

Activist historians work backwards toward the beginning, therefore picking, manipulating, and choosing historical records to fit their end goal. Gilley does the opposite by taking the beginning, in this case German colonialism of the 19th century, and moves forward, pulling records and statements from those in German governmental authority and then colonial authority (including the original purpose of German colonialism as promoted in the “Spirit of Berlin” conference)―both good and bad―and ties them together to weave a conclusion that is indeed opposite of the activists’.

Does his conclusion create moral clarity for colonialism? I don’t think it does. But I don’t believe that is the point. Colonialism is a rather morally ambiguous topic especially in an era that was full of revolutions, independence movements, and, in the words of Woodrow Wilson, “self-determination.”

To some extent, one should consider Thomas Sowell’s idea of “trade offs” when considering colonialism. According to the American economist Sowell, there are no solutions, only trade offs. Gilley pits the idea of “trade offs” against itself. Should a tribe or nation in Africa subject itself to European authority and lose what the West would consider its independence? Or continue as a tribe or nation that in many parts remains centuries, if not millennia, behind the rest of the world?

Gilley references the Germans’ “Spirit of Berlin” principles to indicate that the goal was to uplift a group of people by instituting law and order, economic prosperity, technological and medicinal advancements, infrastructure, and education, with the sacrifice of pure autonomy.

Activists promote the idea of pure autonomy even if it means sacrificing the aforementioned. In the closing chapters of his book, Gilley notes the results that came from those “independence movements” in Africa. They resulted in most often nothing short of chaos and violence.

Gilley indicates several theories might be driving forces of anti-colonialism. One is “group-guilt,” which is the idea of taking an exception and making it the rule. In this instance, the exception is necessarily negative. But Gilley refutes this idea, writing, “On such a ‘group guilt’ theory, every contemporary country is illegitimate, genocidal, and evil because every country has at one time experienced major policy lapses that have had terrible consequences.”

A tie-in to the “group guilt” theory is the use of “micro-history,” a term used by Rebekka Habermas in her book, “Scandal in Togo: A Chapter of German Colonial Rule.” Gilley uses Habermas’s work and theory against her, and along with it the “group guilt” theory, by stating that “if anything, we should assume that a scandal is a scandal because it is not typical” (italics in the original). These gloss-over accusations by contemporary scholars and historians are the bases for Gilley’s work.

Furthermore, the author believes that this purposeful misconstruing of German colonialism―which reaches back a century to the post-World War I British, French, and Belgian propagandists―gave rise to communism in Germany and ultimately the Nazi party. Of course, the British and French had their reasons to create such propaganda, as the conclusion of The Great War gave rise to the opportunity to take the available German colonies.

But how does the Third Reich fit in with anti-colonialism? Aren’t colonialism and fascism synonymous? Gilley maintains they are not and that they could not be more opposite. He argues that considering them synonymous stems from ideology. “The biggest failure is ideological,” he writes. “Scholars wish ardently to believe that colonialism and fascism were two heads of the same monster.”

He later argues, “The Nazi doctrine was perfectly aligned with the doctrines of anti-colonialism.” Pointing to modern scholars, he writes, “Strangely, the contemporary academy is completely silent on the fascist origins of anti-colonialism. … They simply do not want to admit that the anti-colonial movements they admire are rooted in fascist ideas and connections.”

Gilley argues that the reason these modern scholars are silent is because they adhere to the German-American historian and political philosopher Hannah Arendt’s “continuity thesis.” It states that fascism, Nazism specifically, sprouted directly from the seeds of colonialism. But even without Gilley’s dissection, this thesis doesn’t hold water. Arendt’s “continuity thesis” only works if one works backwards, but as aforementioned, counter historical facts must be ignored or misrepresented.

Gilley may be poking the modern intellectual bear by making a more important point: These types of scholars suffer from ideological servitude and laziness. It is the equivalent of the one fish swimming upstream while the others swim downstream: The group finds the downstream trip easy.

But why is this mode of historicism, as I suggested above, destructive? It should never be more evident than what the West has witnessed over the past decade of tearing down statues, destroying monuments, rewriting history, and educating the next generation to advocate for politically and socially motivated theories.

Gilley describes it even more chillingly, stating that “Germany succumbed to an all-embracing and debilitating ‘guilt politics’ that cast its flourishing era of liberal internationalism … as an unbroken tale of oppression.” He then describes what has resulted from this “guilt politics,” writing that “[Germany], which above all countries should have emerged from the Cold War as the unrivaled bastion of the Western-liberal and capitalist tradition, became instead a self-doubting wreck of a country that dared not speak its own name.”

Though Gilley has written a powerful testament that undermines the scholarly activism of many decades (and he is not alone in this, as he does reference numerous other scholars who believe as he does), he is also pointing the reader to something else, something bigger. It’s the fact that we are all being scammed by revisionist historians who advocate for a political ideology rather than what is true, whether that truth is positive or negative.

If colonialism was as terrible as the contemporary rhetoric proclaims, then let the records speak for themselves instead of being filtered through the “guilt” theories and theses. The problem is that history, the history of the morally ambiguous, has been so overwhelmed and buried by ideological activism that the average reader will struggle to believe anything that Gilley suggests. His book appears as another ideology rather than a correction of history. His use of insulting adjectives regarding many of these scholars makes it seem so. There is no camouflaging his irritation and anger about something we should all be irritated and angry about.

The problem is that the pathos in our modern historical conversation plays too large a role. Posterity is worth fighting for because our view of our own history decides our future. History doesn’t need hyperbole; the truth is enough.

‘In Defense of German Colonialism: And How Its Critics Empowered Nazis, Communists, and the Enemies of the West’

By Bruce Gilley

Regnery Gateway, Aug. 2, 2022

Hardcover: 256 pages