Alzheimer’s disease takes a long time to progress. Is there any way to intervene at an early stage to slow its progression? In this article, we will discuss one factor for Alzheimer’s disease that can be modified within the first five years of diagnosis, as discovered by researchers.

- Individuals with steadily increasing symptoms of depression had a significantly higher incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.

- The best way to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease is to reduce depression levels early.

- The best time window to decelerate the progression of Alzheimer’s disease is within the initial five years, not beyond.

Alzheimer’s disease is the leading cause of dementia and is responsible for around 60 to 80 percent of all dementia cases. It is a degenerative disorder that affects the brain, causing a progressive memory decline, thinking, and behavior, leading to loss of independence and eventually death.

Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, and it is considered irreversible. As the disease progresses, it becomes more debilitating and can devastate an individual’s quality of life, and that of their family and caregivers.

The progression of Alzheimer’s disease can vary from person to person. Nonetheless, providing intervention during an early window is crucial to help slow the disease’s progression and thus improve quality of life.

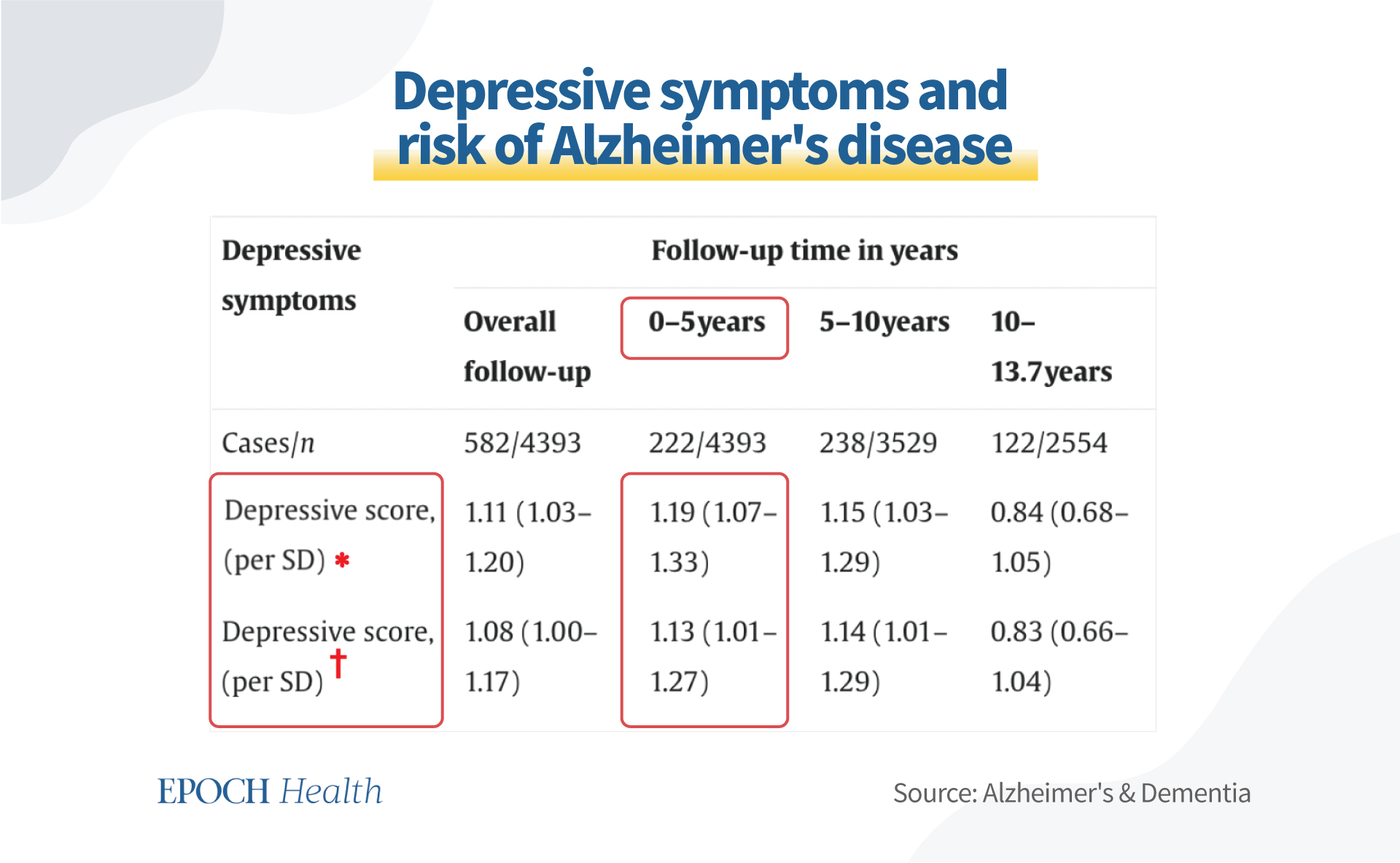

In a study of 4,393 older adults with a mean age of 73 years, participants were followed up to 13.7 years for the incidence of dementia. In this research, the authors repeated the analysis matching for incident stroke, restricting the results to only Alzheimer’s disease as an outcome.

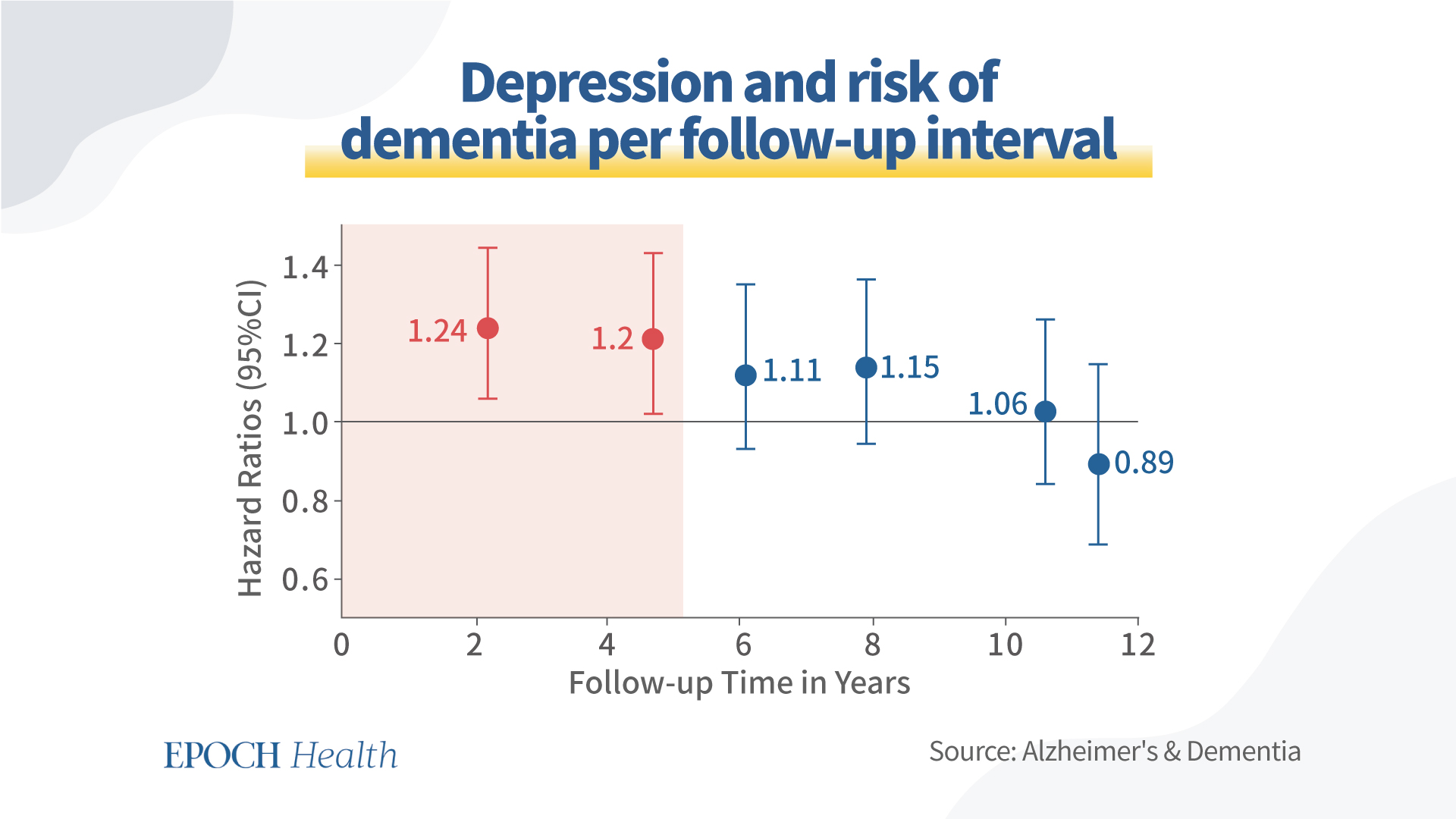

The results showed that individuals with depressive symptoms had an 8 percent increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease throughout the follow-up years. While depression within the initial five years could increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease by up to 20 percent, the incidence of depression after the five-year window could not increase the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. The data are presented in the following figure.

The data in the following table show that depressive symptoms increased significantly within the first five years.

To eliminate potential bias from other Alzheimer’s disease risk factors, the data was analyzed after adjusting for age and gender, as well as smoking, education, hypertension, diabetes, prevalent stroke, Mini-Mental State Examination score, and antidepressant use.

The data indicated that depressive symptoms could be seen as an early nonspecific behavioral manifestation of a brain under physiological stress, and depression is a common antecedent and an early sign of Alzheimer’s disease.

The researchers examined data from the first 10 years of follow-up on individuals with a history of depression and published their findings in the journal Lancet Psychiatry. Among all risk factors, it was revealed that people with increasing levels of depression had a higher incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.

Furthermore, when comparing severe and mild depressive symptoms, the risk of Alzheimer’s disease could increase by 44 percent in those with severer symptoms.

Though the risk of dementia varied according to the length of depression history, the higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease demonstrated in those with severer depressive symptoms suggests that depression may be a prodrome of Alzheimer’s disease.

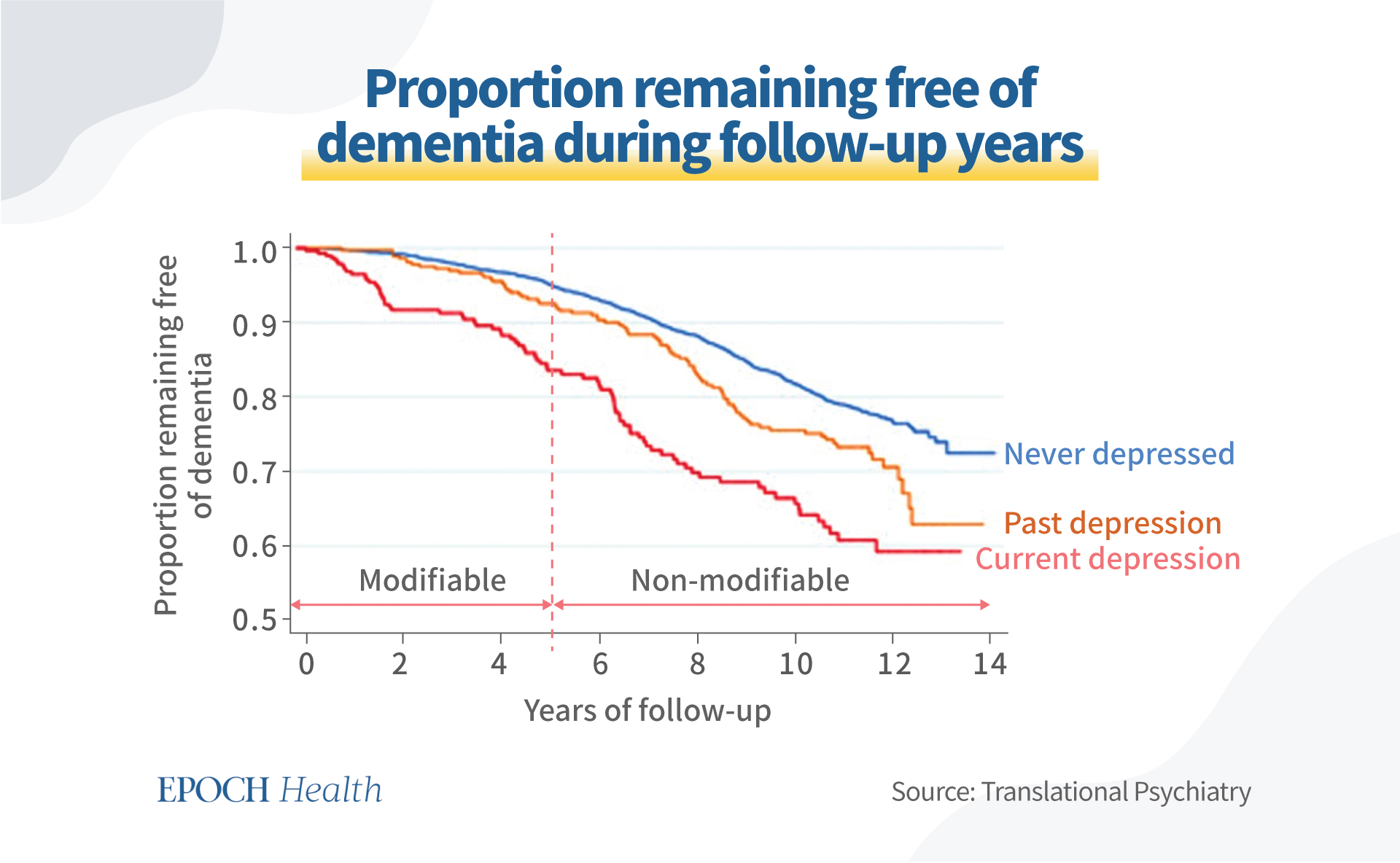

A 14-year longitudinal study of 4,922 cognitively healthy men aged 71–89 years suggested that depression as a modifiable factor could be used to decrease the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease.

The following graph demonstrates that the proportion of participants remaining free of Alzheimer’s disease decreased 1.5 times in the “current depression” group, compared with 1.3 times in the “past depression” group. The proportion decreased by 18.3 percent in the control group (those who had never been depressed).

Most importantly, this study demonstrated that the first five years were a modifiable window for individuals to take action to reduce depression and thus reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease; after the five-year window, Alzheimer’s disease tends to be too severe for individuals to intervene.

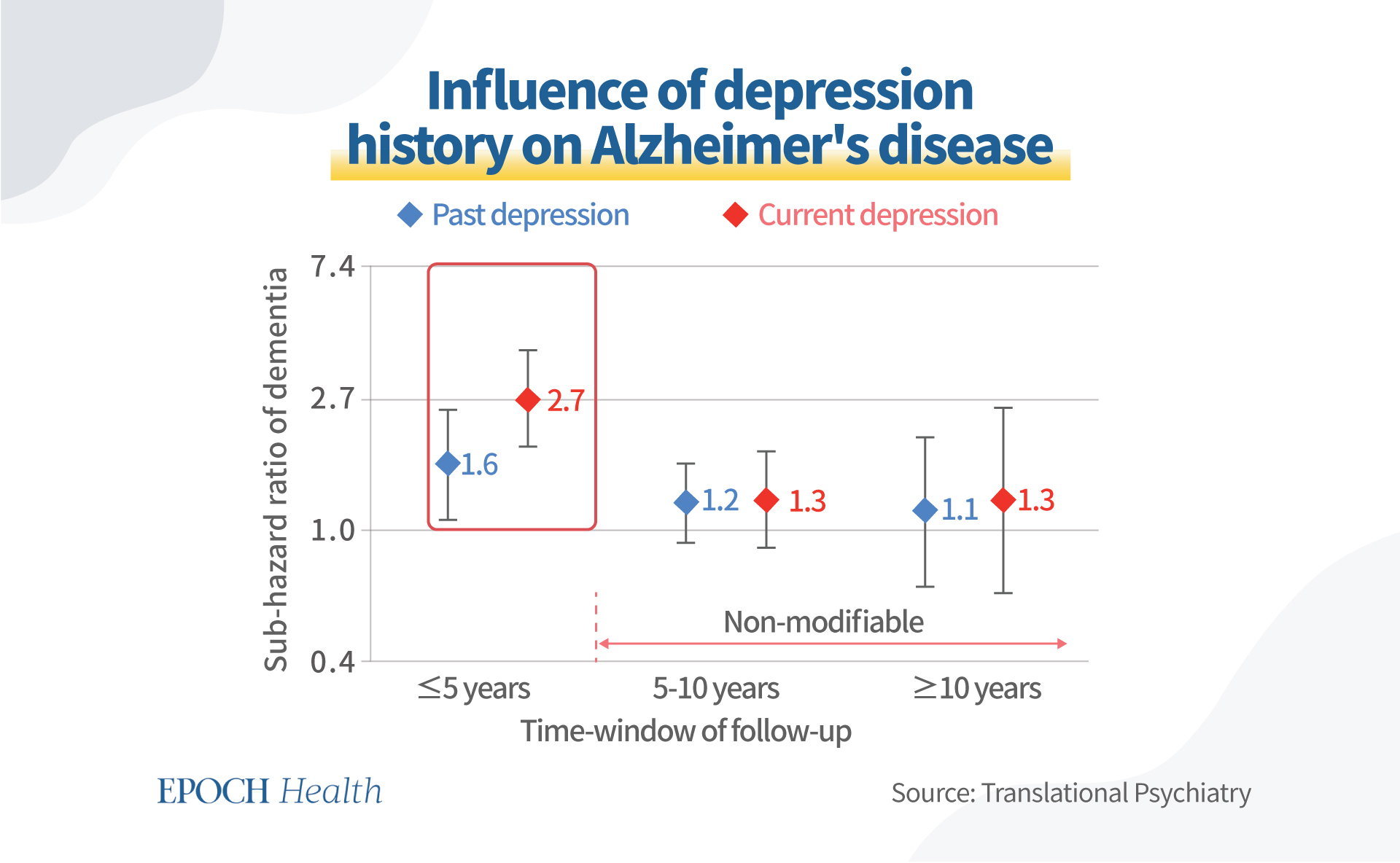

The number of men who developed Alzheimer’s disease during the initial five years of follow-up was 2.7 times higher than in those without depression, while past depression history only made the incidence 1.6 times higher.

After five years, there was no significant difference in the dementia-incident ratio compared with the incidence in current and past depressive history.

The figure below shows the risk ratio of Alzheimer’s disease in past or current depressive individuals according to the timing of the follow-up.

According to the research above, depressive symptoms began years before Alzheimer’s disease was identified, and people with continuously worsening depressive symptoms had a noticeably higher incidence of the disease.

With this in mind, researchers proposed that Alzheimer’s disease and depression might stem from the same source.

First, the biochemical mechanisms behind depression and neurodegenerative disorders share many similarities at the molecular level, including inadequate antioxidant defenses, impaired neurogenesis, elevated apoptosis, dysregulated immune systems, etc. The observed correlation might be explained by several biological mechanisms or by the interaction of those mechanisms.

Second, reduced hippocampal volumes, vascular changes in the brain, and neurotransmitter deficits are common findings in depression, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. These modifications have been linked to chronic inflammation, which might be involved in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

Third, low folate status has been linked to dementia—particularly Alzheimer’s disease—and depression in the elderly population, according to a review of population-based studies. That is to say, folate deficiency plays a vital role in the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

According to the findings, people who have depressive symptoms are more likely to develop dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, these associations were strongest for short follow-up periods, i.e., less than five years, and they weakened with increasing follow-up periods.

Depressive symptoms were found to predict Alzheimer’s disease in the short term but not in the long term.

As a result, the incidence of depression may aid in identifying people at high risk of clinical early-stage Alzheimer’s disease.

Epoch Health articles are for informational purposes and are not a substitute for individualized medical advice. Please consult a trusted professional for personal medical advice, diagnoses, and treatment. Have a question? Email us at HealthReporter@epochtimes.nyc