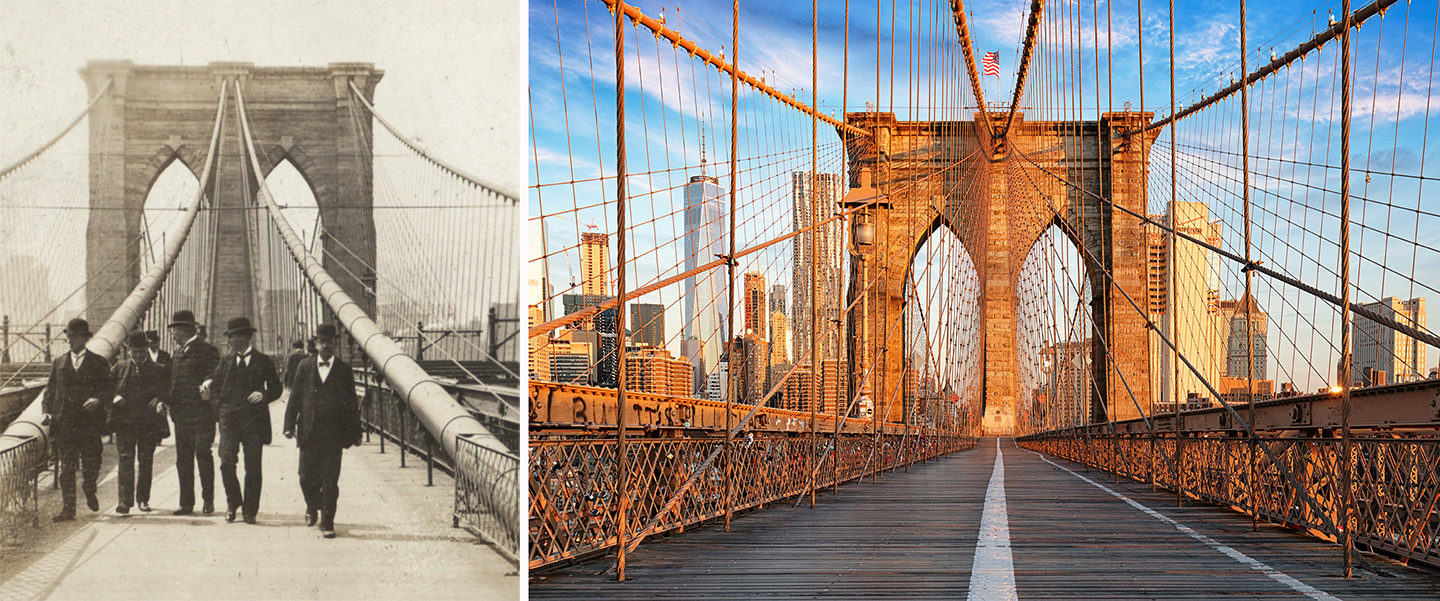

After many long years of planning and building, along with numerous setbacks, the Brooklyn Bridge opened to traffic on May 24, 1883.

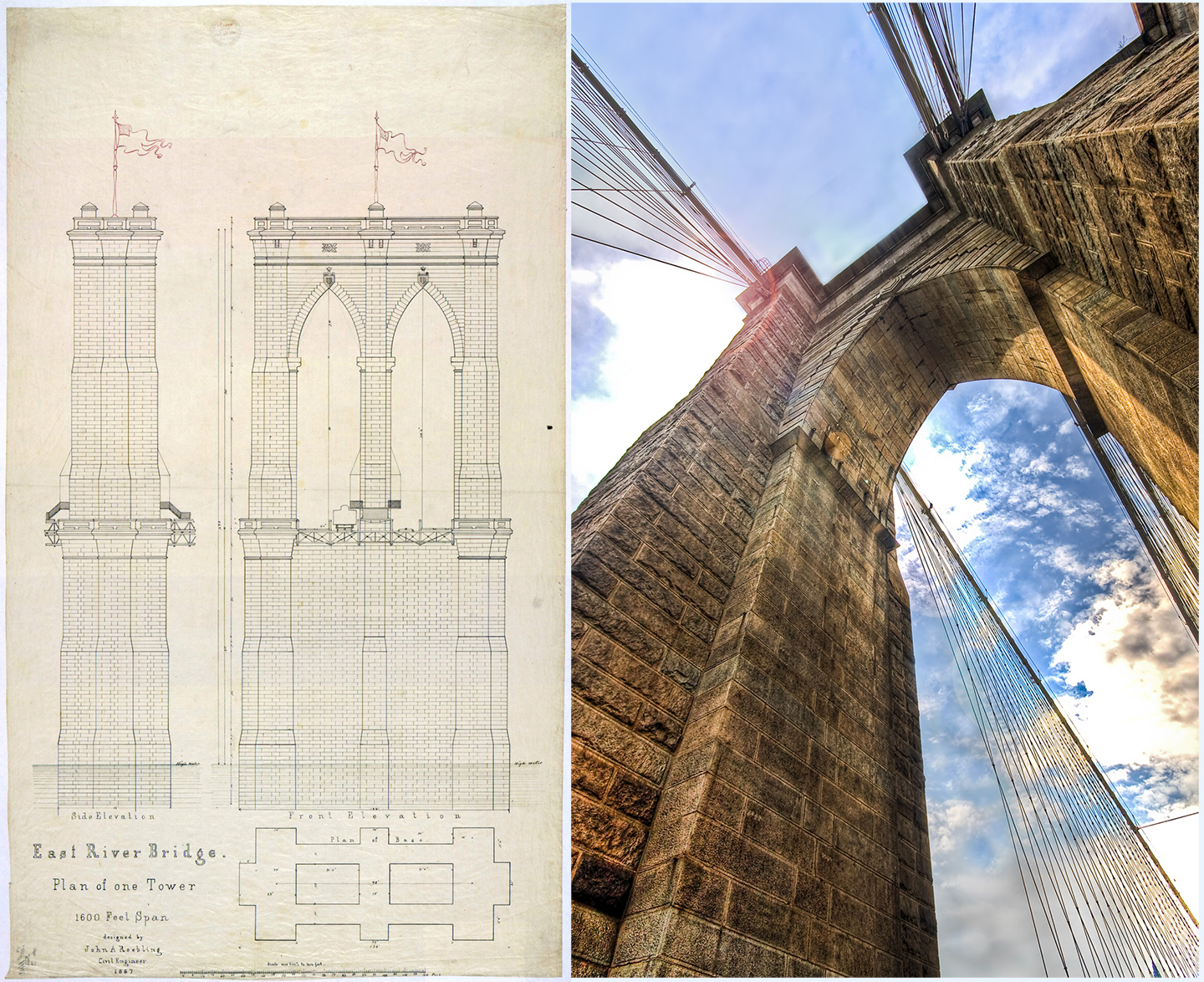

The first vehicle to cross the bridge was Emily Roebling’s horse-drawn carriage. Emily carried with her a rooster in a cage symbolic of the victory realized that day. The victory was wrought from the darkness of the bridge’s deep underwater foundations, now realized in the vast structure that towered in the light traversing the river. As Emily gazed up at the bridge’s great gothic arches, which resembled the windows of a mighty cathedral, she reflected on her 11-year struggle, carrying a torch passed to her from her father-in-law, John Roebling, and her husband, Washington Roebling. Before the Brooklyn Bridge could come to symbolize a mighty American city, it had to begin with the vision of one man.

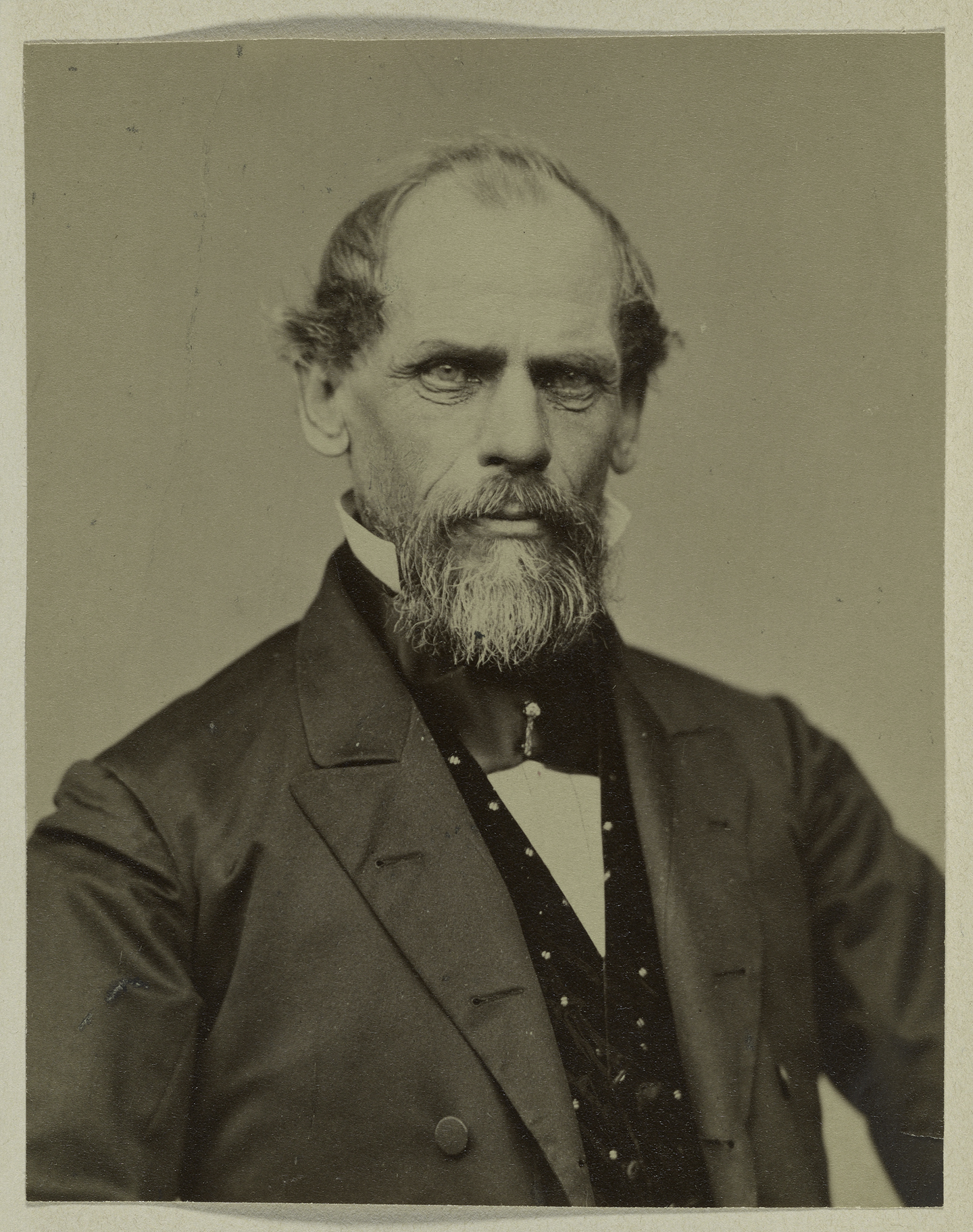

John Augustus Roebling was born (Johann August Röbling) on June 12, 1806 in Mühlhausen, in the Kingdom of Prussia (now part of Germany). His mother saw that he was somewhat of a “wunderkind” (child prodigy) and sought out education for him in math and science at a young age.

He sat for the surveyor’s examination at 18 and then attended the Bauakademie (Building Academy) in Berlin. At 19, he obtained a job designing and supervising the construction of military roads. During this time, he actually sketched the concept for several suspension bridges, though they were never built. At the time, suspension bridges were built with large chain links fastened together to hold up the roadway. These chain suspenders sometimes failed, but Roebling was still fascinated by them.

Leaving government service in 1828, Roebling returned home to study for his engineer’s exam; he never took it. Instead, he made plans to come to America. Roebling and his brother Carl purchased 1,582 acres of land in Butler County, Pennsylvania. They called their settlement Germania, and took up farming. Eventually the settlement, near Pittsburgh, came to be known as Saxonburg. Roebling struggled as a farmer, however, and as canals and railroads were being built throughout western Pennsylvania, he found ready work as an engineer.

The Allegheny Mountains stood in the way of a direct water connection between Philadelphia and Pittsburg. The canal designers, rather than spending years building locks or tunnels, decided to build a portage railway. Canal boats would be carried on large rail carriages across the high mountain terrain. The weak link in this system was the hemp rope used to tow them. It would often snap with disastrous results. Roebling thought he had a better idea. In his shop behind the town church, he experimented with weaving a rope from steel wire. The tensile strength of his “wire rope” far exceeded that of hemp.

The wire rope was a boon to the canal operators, who regularly had to replace the hemp. Not only was it important to canal operators, but it proved to be a superior material for suspension bridges as well. Some of Roebling’s first suspension bridges actually carried canal boats across aqueducts—a technology made possible by the properties of his woven wire. In fact, the oldest steel-wire suspension bridge in the United States is Roebling’s Delaware Aqueduct. It was opened in 1849 to carry the channel of the Delaware and Hudson Canal across the Delaware River. It has since been converted into a highway bridge.

In 1848, Roebling moved his wire-making operation to Trenton, New Jersey, where he built a huge factory complex. He built an enormous suspension bridge with two levels—one for vehicles and one for trains—across the Niagara Gorge to carry traffic between New York and Canada. Roebling’s son Washington joined his father in 1858 and became his business partner. John Roebling was an exacting taskmaster, not an easy man to please, but when Washington married Emily Warren in 1865, the brilliant young woman won her father-in-law’s heart.

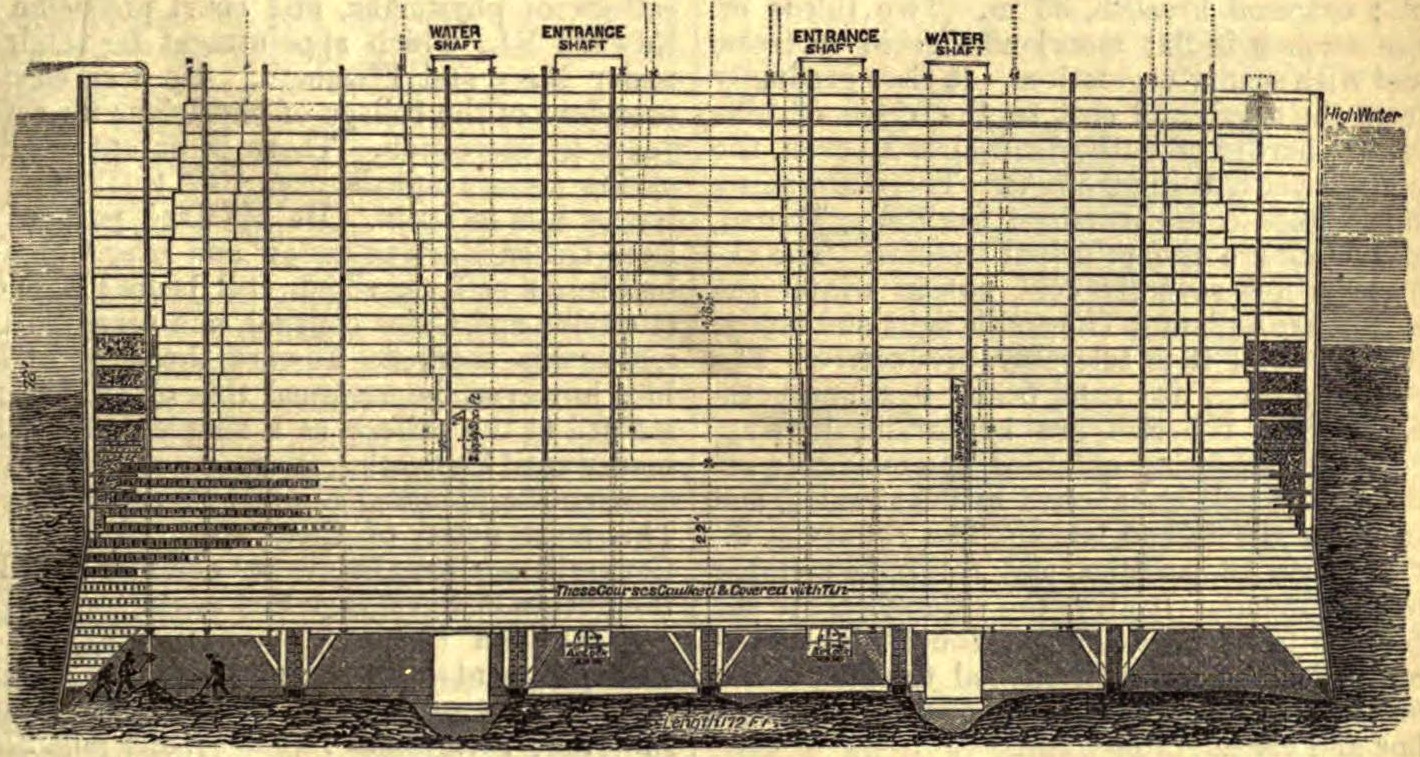

As Manhattan and Brooklyn grew, commuters were at the mercy of the ferry boats, and the ferry boats were at the mercy of the weather. Having been stranded on an icebound ferry on the East River, Roebling was inspired to pursue the construction of a bridge across that great and turbulent body of water. Building that bridge would require building foundations for the towers far beneath the river. The newly wedded Washington and Emily went off to Europe to study the use of caissons to construct a bridge. A caisson is a watertight wooden box with an open bottom, sunk to the floor of the river, with the water forced out by pressurized air. This allowed men to excavate, pour concrete, and lay stone to build the towers.

In 1869, Roebling was just beginning his surveys for the great bridge, having successfully sold the proposal for the Brooklyn Bridge to the officials of Manhattan, the then independent city of Brooklyn, and the State of New York. In a freak accident that first day, his foot was caught in a gap in the pier just as a ferry boat landed, crushing his toes. His toes were amputated but tetanus set in. Within weeks the great engineer was dead. Washington took over as the chief engineer. He worked tirelessly, going down into the caissons to check details and supervise construction. However, in the 19th century, no one really understood caisson disease, or “the bends.” It was caused by ascending too quickly from a highly pressurized environment to surface pressure, resulting in trapped nitrogen expanding into the body.

It was painful. It could severely cripple you, and Washington became a victim as he went rapidly back and forth into the caissons. The cause of this malady would not be understood until the turn of the century, long after it had permanently crippled Roebling. He was confined to his bed in a house overlooking the river where he could watch the towers rise. Some wanted to remove him as the chief engineer, but Emily went to his defense. She had proved to be an able student of her husband’s methods, and she took over much of the supervision of the bridge’s construction. Communicating constantly with her bedridden husband, she checked details as towers rose, steel wires were spun into supporting cables, roadway structures were hung, and the graceful bridge came into being.

She performed this service for 11 years, and many felt that she’d even had a hand in the bridge’s design. Whatever the case, her role as a collaborator in the project was clear. It had taken 14 years and $15 million to build. At the time of its completion, its center span, at 1,600 feet, was the longest in the world.

President Chester A. Arthur and then New York Governor Grover Cleveland were in attendance for the dedication of the “eighth wonder of the world.” Emily made the first vehicular crossing in her horse-drawn carriage. The rooster she carried on her lap, the bird always announcing the dawn of a new day, was a clear allusion to the victory of light over darkness. That day, over 150,000 people walked across the bridge on the promenade above the roadways that was built solely for the joy of it—as they still provide today!