“Always scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh, Mr. Gibbon?” These words, alternatively attributed to King George III and the Duke of Cumberland, make mocking reference to Edward Gibbon and his massive work, “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.”

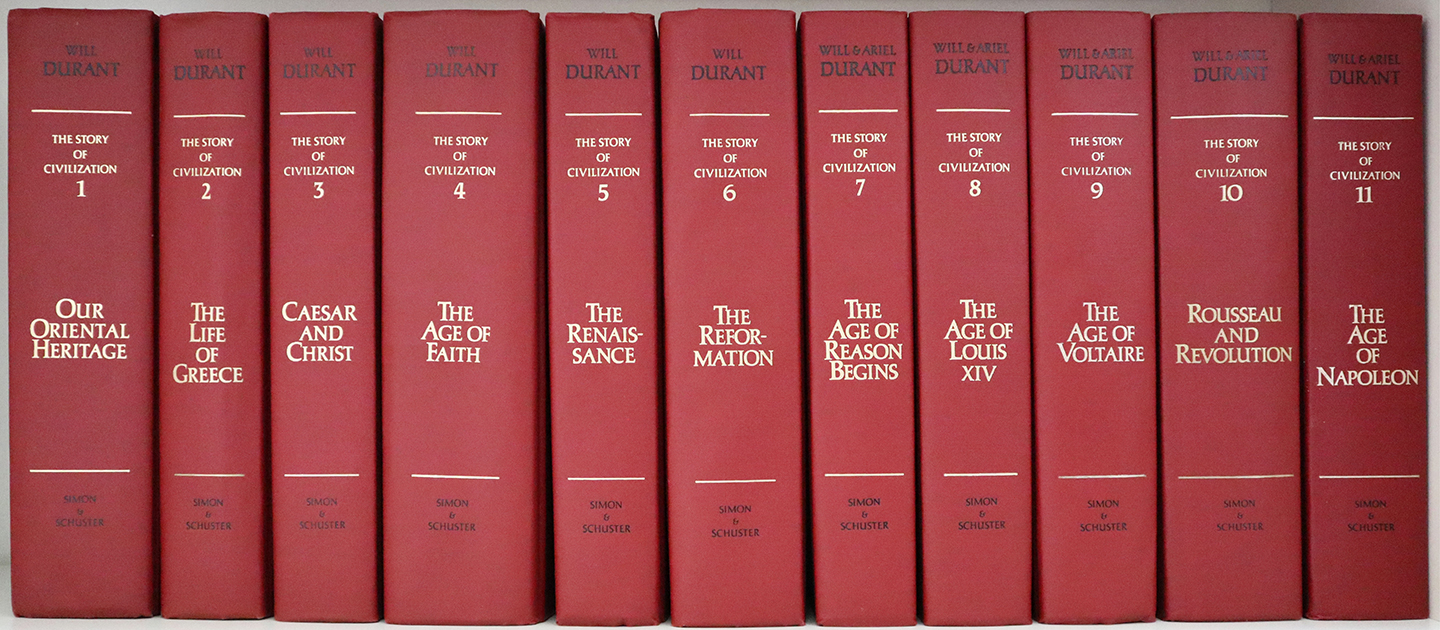

One wonders what these gentlemen might have thought of some historians of the 20th century. Along with his political involvements and defeating Nazism, Winston Churchill wrote a shelf full of books, most of them histories, and for a time earned a living as a journalist as well. Will and Ariel Durant gave readers the 11-volume set of “The Story of Civilization,” which weighs in at 36.6 pounds. More recent disciples of Clio, like Stephen Ambrose and David McCullough, composed numerous histories and brought the past to life for the rest of us.

Standing in this company of prolific authors is historian Paul Johnson (1928–2023).

On Jan. 12 of this year, Johnson “popped off,” as he once put it in an interview. His death brought numerous tributes, some of them containing rebukes of his conservativism, from many newspapers, magazines, and online commentators.

During Johnson’s long life, and in addition to his journalism and commentary, he wrote over 50 books, most of them histories or biographies. Some of these were relatively slim, like his studies of Socrates and Isaac Newton, while others, such as “A History of the American People” or “A History of the Jews,” were tomes whose girth matched their subject matter.

And while some of these works already sit untouched in our libraries, others will be read by students of history for years to come.

Paul Johnson received his pre-university education at a Jesuit school, Stonyhurst College, and a degree from Magdalen College, Oxford. After serving out his national service in the Army, he then found his way into journalism.

For over 20 years, Johnson was a man of the Left, serving, for example, as the Paris correspondent of the New Statesman and eventually become one of its editors. Beginning in the 1970s, however, he became increasingly conservative, opposing in particular the radical policies of Britain’s trade unions.

After Margaret Thatcher became prime minister in 1979, Johnson, who’d known her at Oxford—“She was not a party person”—became one of her close advisers. He continued as well to play the man of letters, placing reviews and columns in a variety of outlets, including Britain’s conservative weekly, The Spectator, and the New York Times.

Meanwhile, he was also writing his books. One of these, his 1983 “Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Eighties,” later updated to include the events of the 1990s, proved enormously popular among American conservatives, so much so that it inspired a 1994 collection titled “The Quotable Paul Johnson.” A fast writer, capable of producing several thousand words a day, Johnson put out book after book into the first decade of the 21st century, winning applause from some quarters and fury at his opinions from others.

Regarding his personal life, in 1958 Johnson married psychotherapist Marigold Hunt, with whom he had four children, a daughter and three sons. Following in the footsteps of his artistic father, he was also an avid watercolorist who exhibited his work on a regular basis.

Of this profusion of books, perhaps the best known and most popular are “Modern Times” and “A History of the American People.”

Johnson begins “Modern Times” by examining the cultural earthquake caused by Einstein’s theory of relativity. The relativity associated with physics quickly became confused with relativism, so that, as Johnson writes, by the 1920s more and more people had come to believe “there were no longer any absolutes: of time and space, of good and evil, of knowledge, above all of value.” A passionate believer in truth and in strict standards of right and wrong, Einstein “lived to see moral relativism, to him a disease, become a social pandemic. …”

This misapplication of a scientific theory to society and culture can wreak havoc and destruction on societies. Johnson points out several examples of this phenomenon, like this one: “Darwin’s notion of the survival of the fittest was a key element both in the Marxist concept of class warfare and of the radical philosophies which shaped Hitlerism.”

The horrendous damage done by our modern belief in relativism is the main theme of “Modern Times.”

By the time he wrote “Modern Times,” Johnson was a staunch anti-communist, and in this compendium of Marxist evils many readers, including myself, first found a comprehensive history of those crimes against humanity. In addition, Johnson is also a historian who knows the value of entertaining and captivating an audience, which he does through the mass of details and stories he offers throughout the book.

In his 1999 revised version of “Modern Times,” Johnson concludes his masterpiece, with some thoughts about the 20th century that deserve to be cited here in full:

… It was not yet clear whether the underlying evil which had made possible its catastrophic failures and tragedies—the rise of moral relativism, the decline of personal responsibility, the repudiation of Judeo-Christian values, not least the arrogant belief that men and women could solve all the mysteries of the universe by their own unaided instincts—were in the process of being eradicated. On that would depend the chances of the twenty-first century becoming, by contrast, an age of hope for mankind.

I leave it to readers to decide whether we live in an age of hope for mankind.

Johnson begins his 1997 “The History of the American People” with this assertion: “The creation of the United States of America is the greatest of all human adventures.”

That declaration is especially stunning today, when recent polls indicate a steep decline in the pride Americans feel about their country.

Johnson then raises three questions: Can a people “rise above the injustices of its origins” and atone for them? He then asks whether the United States has expiated these organic sins. Finally, he asks whether Americans, who “aimed to build an other-worldly ‘City on a Hill’” and later devised a republic “to be a model for the entire planet,” have made good on these “audacious claims.” He then spends over 900 pages narrating American history and searching for answers to those questions.

Though some for political reasons attacked the book and Johnson’s affections for the country across the pond, he remained a friend of America. When asked during a Dennis Praeger interview how he reacts when an American says, as did Lincoln, that America is the last, best hope of humanity, Johnson responded, “I often say it myself, and I think it’s true.”

And in this narrative history, as in “Modern Times,” Johnson displays that same ability to consider big picture topics without sacrificing details, stories, and anecdotes. Though I’ve read this book twice, and taught it once, Johnson engages and educates me every time I revisit it. In the chapter “The Korean War and the Fall of MacArthur,” for instance, his descriptions of the feisty Harry Truman—his daily routine, his threats of violence in defense of his daughter Margaret when she received a critical review of her concert singing—give us in two pages the essence of that president.

Like Truman, Paul Johnson could be combative. He told one reporter, “Marigold’s often saying to me: ‘Please, Paul, have you not got enough enemies already? Will you take a vow not to get into any more rows?’” His opinions in his histories raised hackles among some critics and readers, especially those opposed to his politics and his misgivings about modern culture, and he often returned their fire with fire.

Sometimes, too, he was off-base in his predictions about the future. In discussing a short biography of Winston Churchill he’d written, Johnson stated, “He made occasional errors of judgment because he made so many judgments—some of them were bound to be wrong!” Those same words apply to Johnson himself, who offered so many opinions and judgments regarding past or present events.

But these criticisms are quibbles when compared to the good we gain from these histories. Like the best of teachers, they entertain, instruct, and make us think. In an address delivered before he wrote any of the books mentioned here, Johnson gave his listeners, and us, one additional important reason for studying the past:

History is a powerful antidote to contemporary arrogance. It is humbling to discover how many of our glib assumptions, which seem to us so novel and plausible, have been tested before, not once but many times and in innumerable guises, and discovered to be, at great human cost, wholly false.