A few weeks ago, I was on a flight from Washington, D.C., to Charlotte, North Carolina. Amid an airline ecosystem rife with cancellations, delays, and overbookings, I was relieved to find the trip relatively uneventful. The crew was on time, the pilots were accounted for, and the weather was clear—the sky a vast and uninterrupted blanket of blue.

Charlotte is an East Coast travel hub, and when we landed, several groups of passengers had connections in the airport for flights that were already boarding. Anxious to make these connections, many people in the back of the plane jumped up as soon as they heard the ping indicating that passengers could unfasten their seat belts. They grabbed their bags from above their heads and tried—mostly politely—to wriggle their way to the front of the plane, repeating “Excuse me” and “I have a connection” like an incantation.

I have been in this position before, and have missed many connections because I wasn’t as proactive as these passengers. But in the process of so many people attempting to make their way to the jet bridge, many other folks were jostled and bumped and asked to let someone skip in front of them when they were in just as much of a rush to get off the plane.

In the midst of this, two middle-aged women—one Black, one white—got into an argument in the aisle. It started quietly, with cutting stares and barbed whispers, and then began to escalate. Passengers who had previously been busy fumbling with their bags turned their heads; flight attendants peeked around the forming line to see what was going on. I was a few passengers behind the Black woman as we made our way to the front. I couldn’t hear exactly what was being said, but I could feel the air intensifying with conflict. The farther we got from the thrum of jet engines, the clearer their words became. As we were walking through the stanchions ushering us past the terminal’s gate, the white woman turned to the Black woman, red with anger, and called her the N-word.

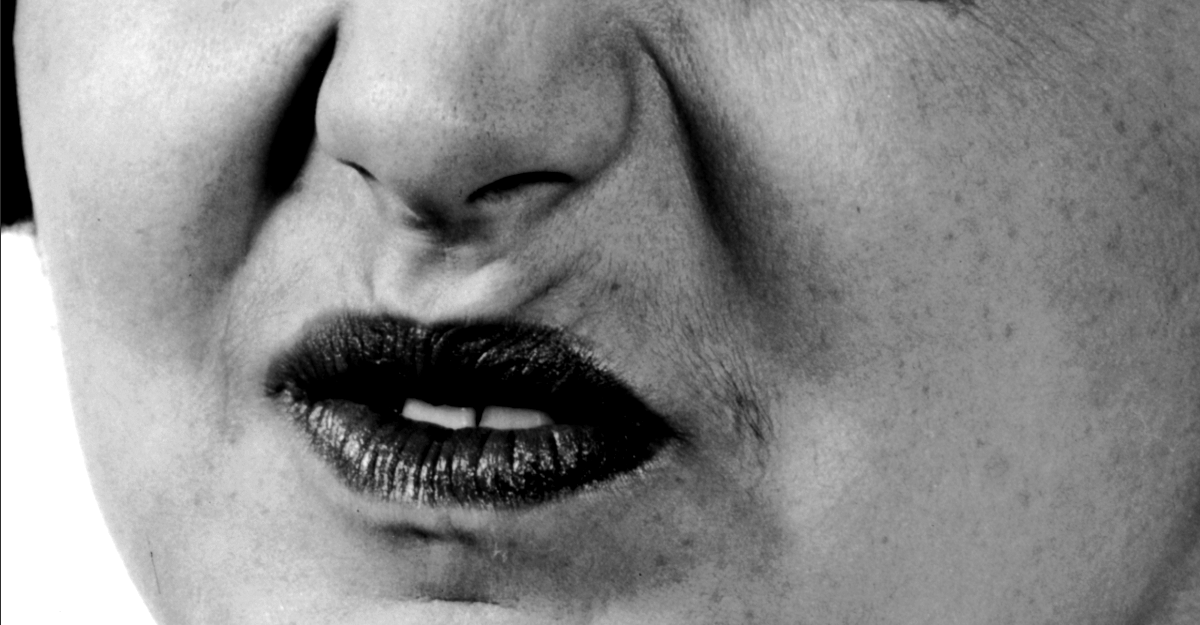

The N-word is a piece of language whose meaning is inextricably linked to the context in which it is used. Our understanding of its implications are necessarily shaped by who is deploying it and how. So it is not that I was unfamiliar with hearing that word out loud; it is that it had been many years since I had heard it used in public, by a white person, in a way that was laced with such unvarnished venom and disgust. It was as if my skin was struck by a match and fire spread through my entire body. My heart’s once metronomic tempo accelerated into a gallop, my blood pumping as if it was trying to tell me to run away. Cortisol was coursing through me. Saliva pooled in my mouth.

In his 1962 essay Letter From a Region in My Mind, James Baldwin describes the “humiliation” he experienced when the word was directed toward him, “I was thirteen and was crossing Fifth Avenue on my way to the Forty-second Street library, and the cop in the middle of the street muttered as I passed him, ‘Why don’t you niggers stay uptown where you belong?’”

It is impossible for me to hear the word, used in that way, without thinking about the stories my grandmother has told me about walking to school as a little girl in the Florida panhandle of the 1940s. White children would, upon seeing my grandmother and her siblings, lower their school-bus windows and throw things at them—apples, oranges, sandwiches, ice cream. She remembers them calling out, “Go home, nigger! You ain’t got no business here.”

It is impossible for me to hear the word, used in that way, without thinking of my grandfather, born and raised in 1930s Mississippi, in a tiny town of less than a thousand people where, when he was 12, a man he knew was lynched. The residue of that word swung from the same tree as the rope.

I cannot hear that word, used in that way, without thinking about violence.

At the gate, the Black woman and I looked at each other as the white woman, suddenly realizing that she’d been overheard by other people, rushed off into the crowd. I think we were both processing what had just occurred, how quick this woman had been to wield that word as the weapon she knew it was, and how quickly she had then run away.

I reached for my phone, thinking I should try to take a video or picture of this woman, but she had already disappeared. We called out to a gate agent who hurried over. We explained what had happened, but by then it was too late. I told the Black woman I was sorry that had happened. She said that she was sorry for both of us. We wished each other well and continued on through the airport in different directions.

Since then, I have replayed the moment many times in my head, wondering if I should have done something differently. Should I have responded faster? Should I have confronted the woman? Should I have stood in front of her to block her way until an airport official came over? But what would I have been hoping to achieve in that? For her to miss her flight? For her to be placed on a list? For her to apologize? Then I imagine the optics of a Black man attempting to physically prevent a smaller white woman from leaving, and immediately recognize the way that such a move would create its own spectacle, its own dangers. And besides, as much as I may have wanted to do something differently, in the moment itself, I was so caught off guard by what happened, and how quickly the woman had run away.

For hours after, I felt the impact of that woman’s word in my body. I couldn’t shake it. This, too, was revealing. Although the venom of her voice had not been oriented directly at me, I experienced the debris of her language. I felt it, quite literally, in and under my skin.

I had felt versions of this before, particularly at times over the past several years when I’ve watched viral videos of Black people being harassed, assaulted, or murdered by police and others in public spaces. The sensations were acutely familiar—not just the sinking of my spirit, but the tightness in my chest. Still, there is something different about being physically present for such an assault—of seeing the woman turn red and place her face only inches away from another woman’s; of watching the spittle leap from her lips.

In recent years we have, necessarily, been paying more attention in our public discourse to the structural and systemic manifestations of racism. We have a more sophisticated understanding than ever of how our landscape of racial inequality is shaped by historical and contemporary policy decisions in housing, zoning, incarceration, immigration, and health care. I think about it in much of my own work. But I was reminded in this moment of the way that interpersonal racism—intimate, direct, one-on-one racism—still affects a person’s body and mind.

You don’t have to be the target of a racist act to experience its harmful impacts. Arline Geronimus, a professor in the department of health behavior and health education at the University of Michigan School of Public Health and the author of the forthcoming book Weathering: The Extraordinary Stress of Ordinary Life in an Unjust Society, coined the term weathering to describe how the toxic stress of living in a racist society deteriorates the bodies of Black people, particularly Black women. What’s more, she finds that this is the case across socioeconomic status, revealing that there is something specific about racism itself that chips away at Black women’s health over time. The journalist Linda Villarosa, the author of Under the Skin: The Hidden Toll of Racism on American Lives and on the Health of Our Nation, has built on Geronimus’s work. She outlines how weathering leads pregnant Black women to suffer disproportionately high rates of infant mortality.

That moment in the airport brought Geronimus’s work back to me. I think of what I felt in my body, and I think of what the Black woman at whom the slur was directed must have felt in hers. How that rising cortisol can kill you if it’s triggered too frequently. How our bodies’ response to that white woman’s word was evidence of what too many still deny.